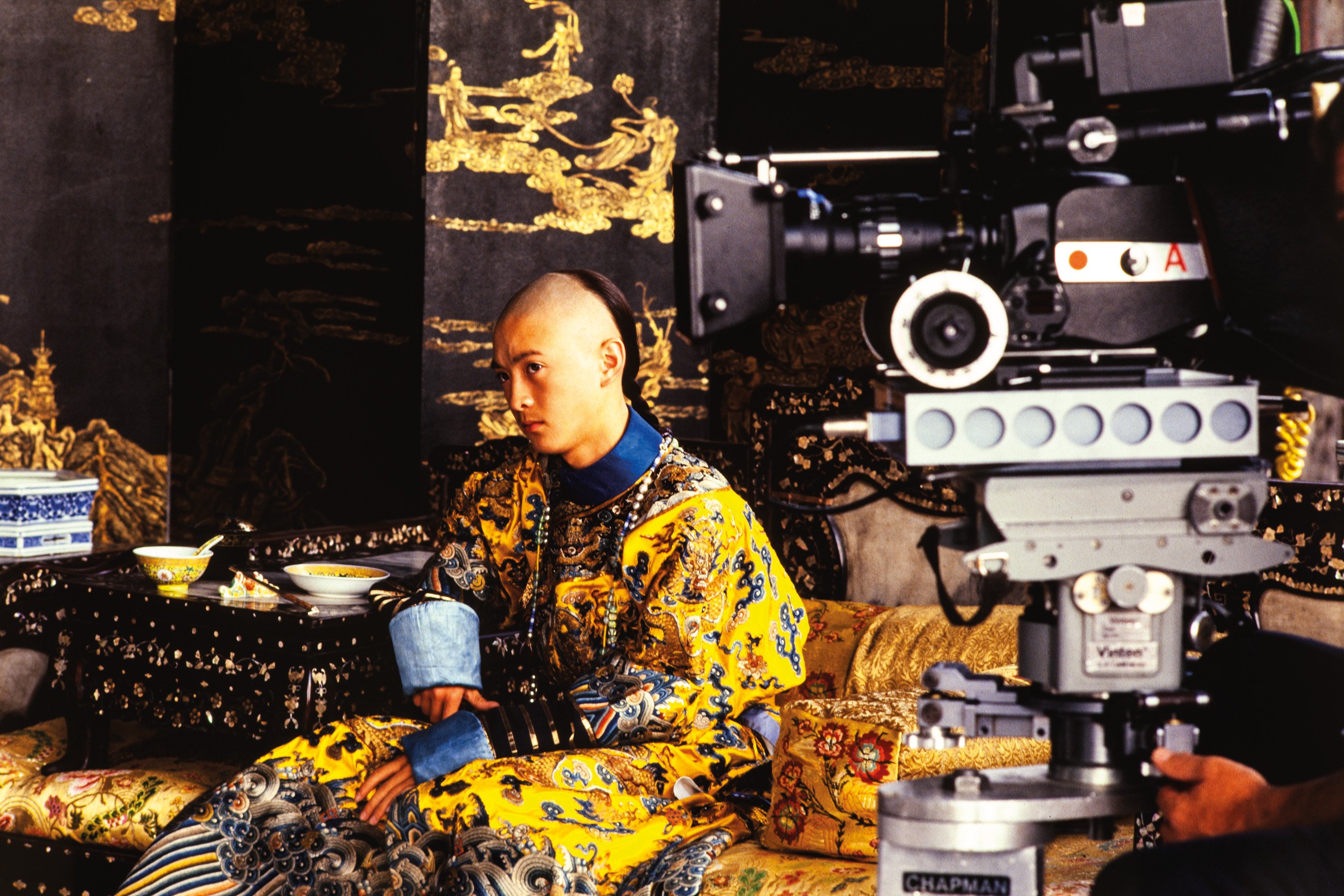

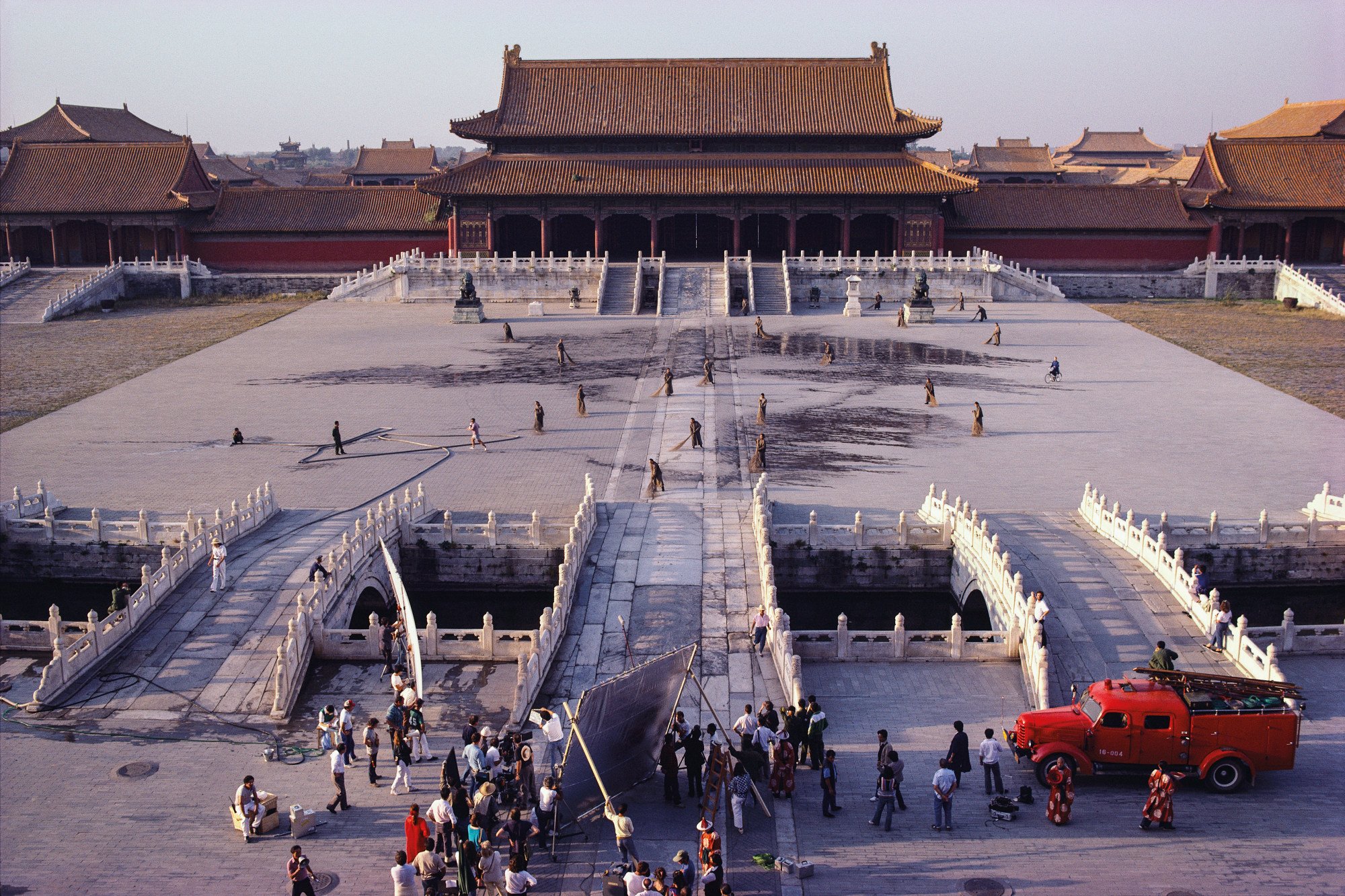

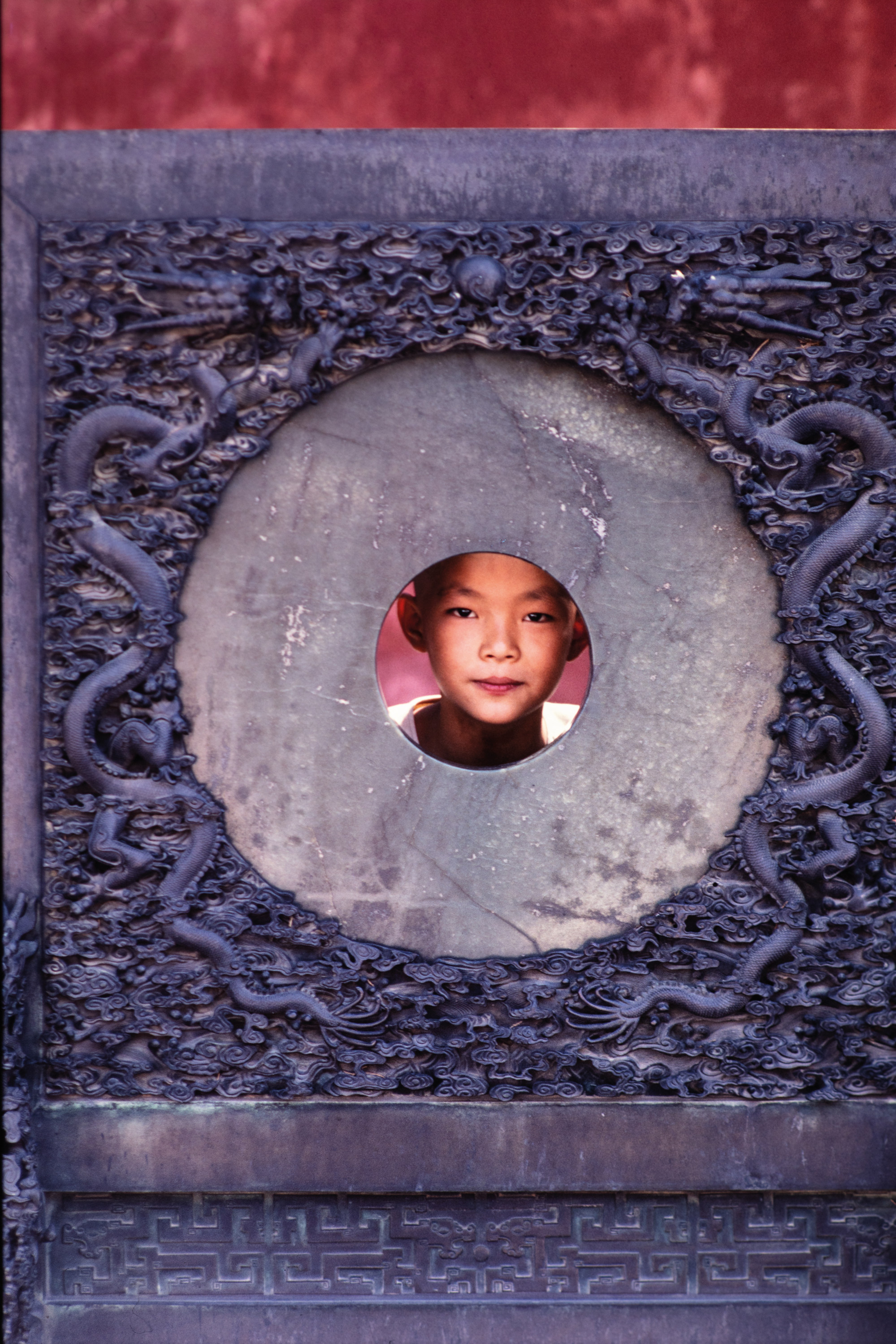

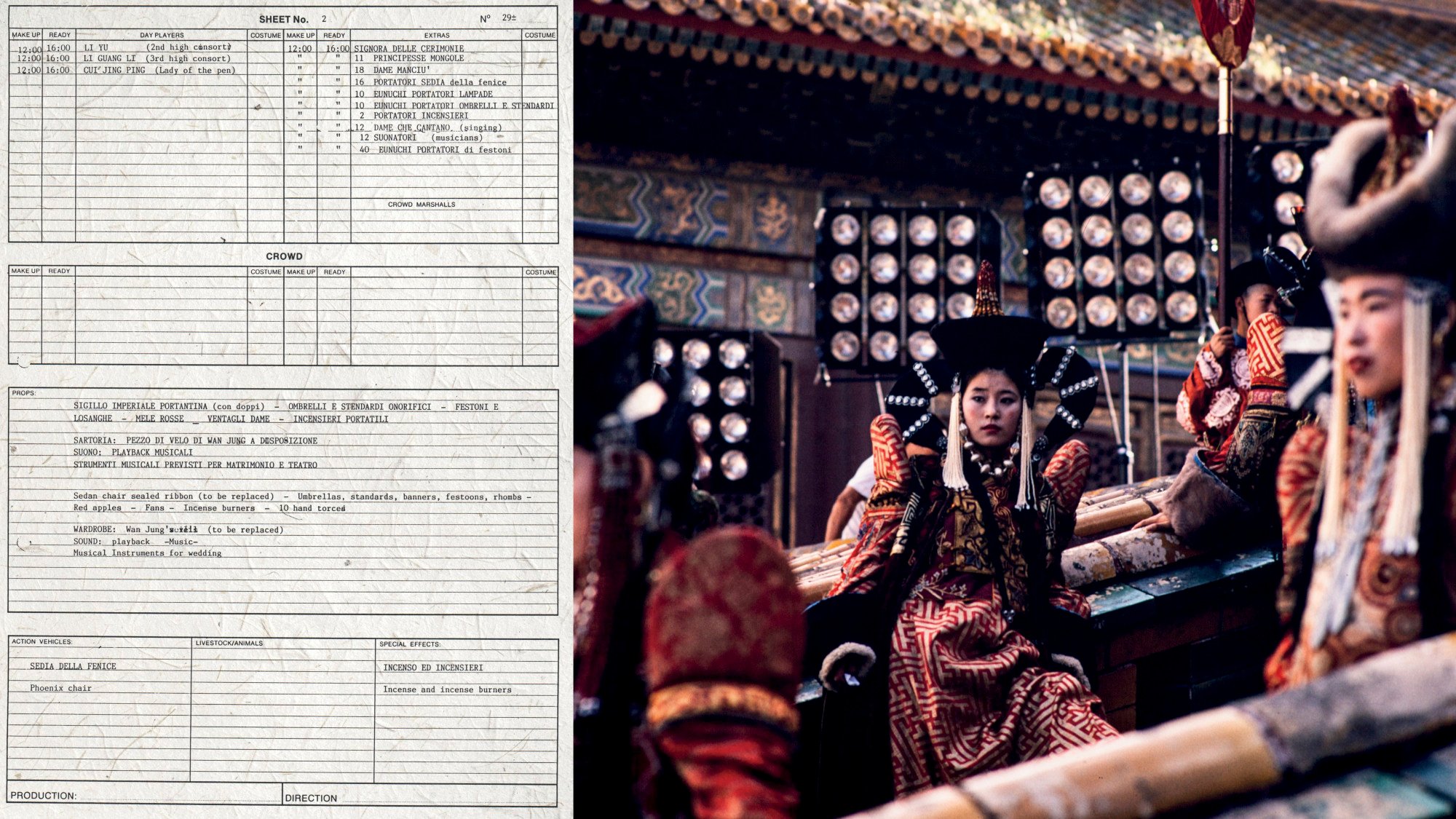

- Basil Pao was allowed unfettered access during the filming of The Last Emperor. Here is a selection of photos from his new book about the making of the epic

Aisin-Gioro Puyi was one of the most extraordinary anti-heroes of modern times, whose life encapsulated the most tumultuous century of change in contemporary Chinese history.

His story can either be described as the metamorphosis of an individual from a dragon to a man, from an emperor to a citizen, or as a journey from darkness to light.

Kidnapped on a gust of wind by history at the age of three, Puyi was set on the Dragon Throne in 1908 as the 11th Qing emperor – “The Son of Heaven” and “The Lord of Ten Thousand Years” – to rule over almost a third of the world’s population as the supreme monarch of China.

Three years later he was forced to abdicate, when revolution swept away 2,000 years of imperial rule and ushered in China’s first republic under Sun Yat-sen.

And while Sun struggled to control the tournament of warlords in the chaotic years that followed, the former Qing emperor was allowed to retain his title and the imperial court remained inside the northern half of the Forbidden City and the Summer Palace.

For Puyi, to be emperor was no game; it was reality. Nevertheless, and unwittingly, he had been cast as the lead actor in an elaborate play performed on the largest stage on Earth, in which the other actors conspired to keep the reality from him.

‘He’s just a kid’: how ‘The Last Emperor’ changed a Mexican beermaker’s life

This elaborate charade finally collapsed in 1924, when Puyi, then 18 years old and married with two wives, was expelled from the Forbidden City by the latest Republican warlord who had captured Peking.

Aided by his friend and tutor, Sir Reginald Johnston, Puyi fled to the International Legations in Tientsin (now Tianjin), where he began to lead the life of a Western playboy.

Puyi craved power and when the Japanese offered to return him to the land of his ancestors he accepted. In 1934, Puyi again became an emperor as titular ruler of Japan’s puppet state of Manchukuo.

Following the fall of Japan and Manchukuo in 1945, Puyi, having spent all his life as a de facto prisoner, found himself in an actual jail with real bars. He spent five years in Siberia detained by the Soviet Union, followed by 10 years of re-education in the Manchurian city of Fushun until he was pardoned and released in 1959.

The first part of the 1987 film The Last Emperor is the fantasy of the child – the Forbidden City, the dying dowager, the high consorts, the concubines, the 1,500 eunuchs and so on. But the real story is about change.

And the most crucial questions are: can a man change? Did Puyi really change? And if so, how much did he change during his re-education in Fushun?

At first, Puyi resisted the re-education process as he was convinced he could not change. The running joke in the Fushun prison yard was that Puyi would become “The Prisoner of Ten Thousand Years”. But, miraculously and mysteriously, Puyi was pardoned and freed after a decade.

Does this mean Puyi had indeed changed? Interestingly, not even Jin Yuan, the prison governor tasked with supervising Puyi’s re-education, was certain whether the prisoner had changed or was ready to do so.

All in all, the story of Puyi, from dragon to man, from emperor to citizen, could be summed up as follows. In Chinese tradition the emperor is the total expression of the collective – “the first to sow and the first to reap” – and ideally the model for all citizens.

In his contradictory existence Puyi never succeeded in being that. Only when he became an ordinary man after re-education did he perhaps become a model citizen.

So was it then, in Mao Zedong’s new China, that every model citizen could somehow achieve the status and the essence of the emperor, resulting in the creation of billions of emperors?

Jean Cocteau once said: “I’ve always preferred mythology to history. History is truth that becomes an illusion; mythology is an illusion that becomes reality.”

And in the story of Puyi, the last emperor, one cannot ignore mythology.

Basil Pao’s new book, The Last Emperor Revisited, is published by Hong Kong University Press. The Last Emperor is being screened in Hong Kong at the Palace IFC cinema at 4.10pm on October 7 and at Movie Movie Cityplaza on October 21 at 1.30pm.