Advertisement

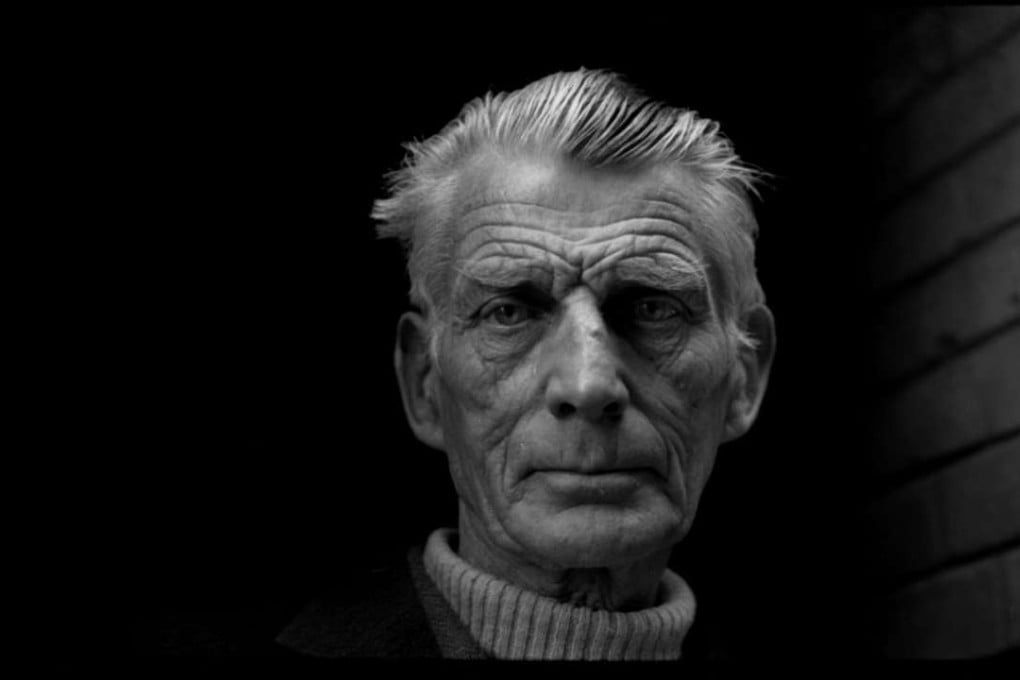

Review | Book review: A Country Road, A Tree by Jo Baker – Samuel Beckett in wartime

A moving, beautifully written and riveting historical novel, British author Jo Baker’s new work is a fictional account of how the still unknown Irish writer survived the second world war in France

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

A Country Road, A Tree

by Jo Baker

Advertisement

Knopf

4 stars

Advertisement

When war came to Europe in 1939, Samuel Beckett was a published but largely unknown and unread Irish writer working in the long shadow of James Joyce, for whom he’d served as a literary secretary in Paris while the great man was writing Finnegans Wake.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x