Review | Book review: Shanghai Grand – a doomed dystopia distilled in three characters

Taras Grescoe tells story of decadence and desperation in late 1930s Shanghai through the lives of writer Emily Hahn and her lover, Shao Xunmei, hotelier Victor Sassoon and his Cathay Hotel

Shanghai Grand: Forbidden Love and International Intrigue in a Doomed World

by Taras Grescoe

St Martin’s Press

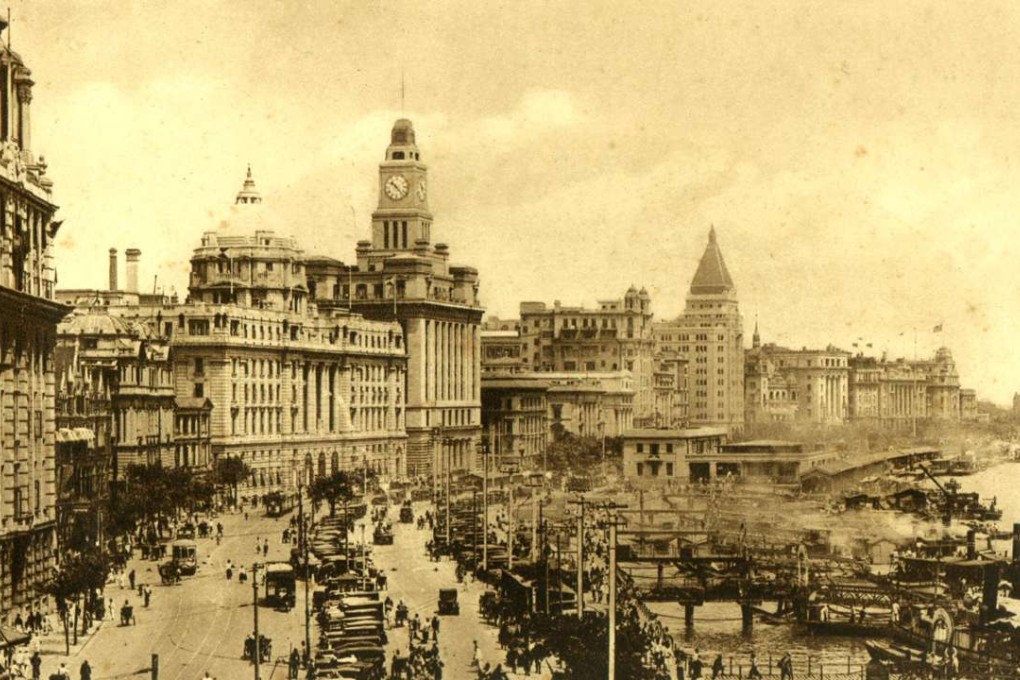

Shanghai in the late 1930s perhaps comes closest to the sci-fi dystopias beloved of Hollywood, full of gilded, sophisticated inhabitants cut off from wasted badlands, served by an abject underclass living as far from the light of day as it does from the consciousness of its masters.

Inside the self-policed boundaries of Shanghai’s International Settlement and its French Concession lay both one of the greatest concentrations of wealth on the face of the planet and some of the most sordid scenes of human misery.