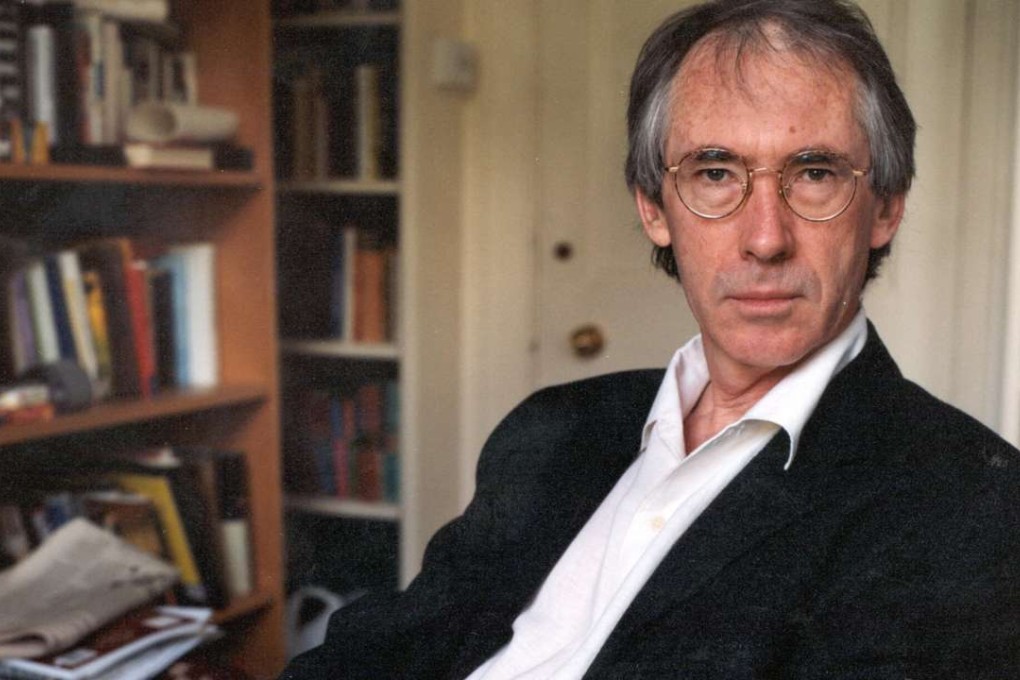

Review | Book review: Nutshell – does Ian McEwan pull off his fetal conceit?

The Booker Prize-winning British author has always been best as a miniaturist – and his latest novel is narrated form the perspective of a baby in the womb who’s surprisingly erudite and well informed

Nutshell

By Ian McEwan

Jonathan Cape

I’m not taking a hammer to Nutshell, although many will wonder how McEwan puts words into a mouth that can’t speak. His solution is to make his baby narrator sound essentially like Ian McEwan. Eloquent to a fault, he is remarkably well informed about his immediate surroundings, and the world at large. He’s even a bit of a know-it-all – talking loftily about James Joyce, quoting Keats and philosophising about global realpolitik.

If bells are ringing, then McEwan’s title and epigraph will clang deafeningly: “O God, I could be bounded in a nutshell and/ count myself a king of infinite space,/ were it not that I have bad dreams.” That’s right: our unchristened fetus is Hamlet by any other name. It’s as if McEwan has taken Polonius’ advice to Ophelia – “Think yourself a baby” – as the idea for a novel.