Review | Author Yiyun Li’s Dear Friend a remarkable feat of prose and understanding

Dear Friend, From My Life I Write to You in Your Life explores the painful formation of a literary mind

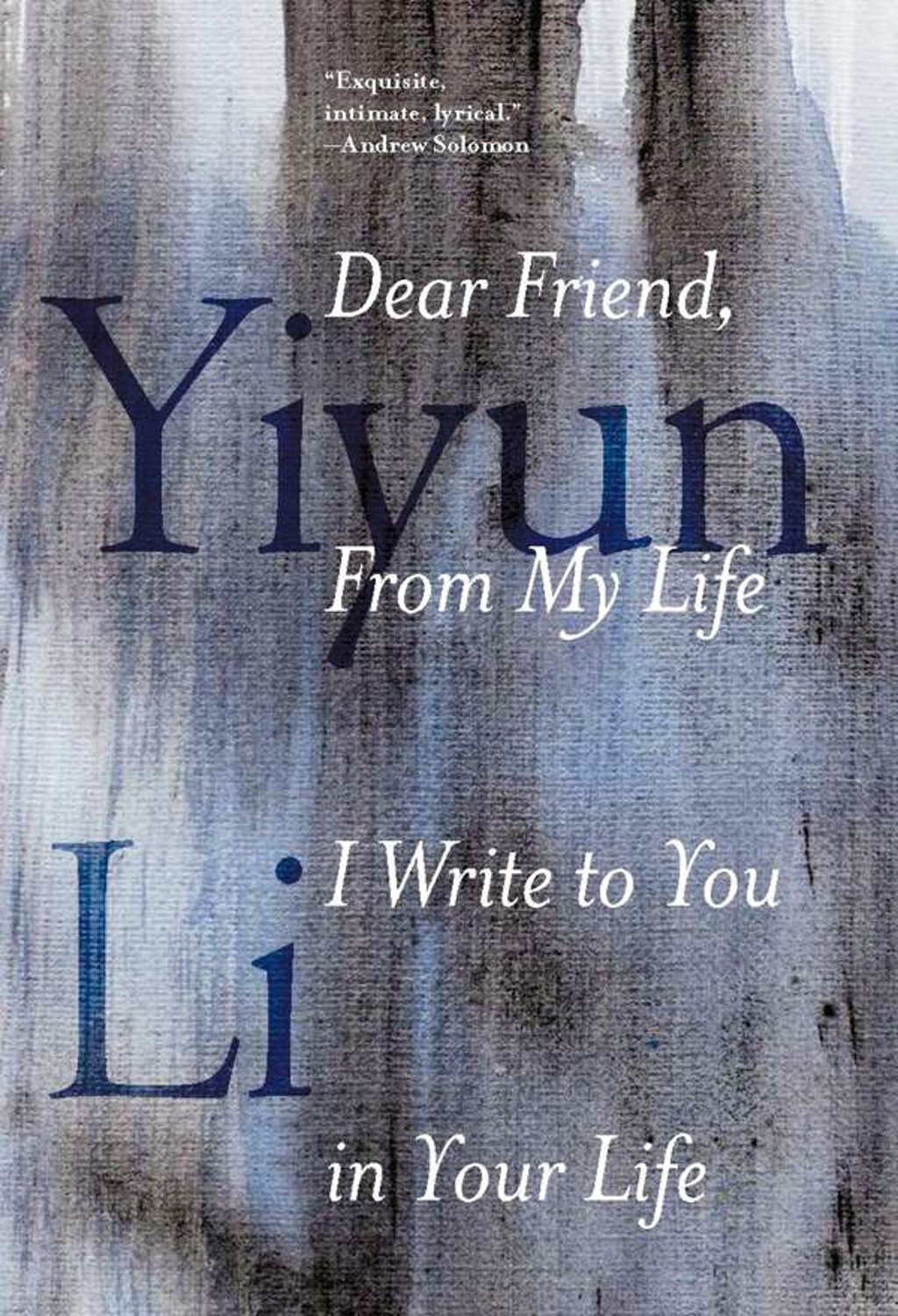

Dear Friend, From My Life I Write to You in Your Life

by Yiyun Li

Random House

This is a remarkable book, both as memoir and as Yiyun Li’s disavowal of the possibility of writing one. Dear Friend, From My Life I Write to You in Your Life explores the formation of the literary mind behind the novel The Vagrants (2009) and short-story collection A Thousand Years of Good Prayers (2005), and is seared with the pain and difficulties of such an undertaking. (If you ever wish to dissuade a child from pursuing a literary career, this book will do it).

This is not to suggest artless diarising. Themes and characters appear and reappear: Li’s mother (a world-class narcissist); her decision to write only in English; her youth in Beijing and military service; two stays in a mental hospital, depression and the appeal of suicide; the authors Philip Larkin, Elizabeth Bowen, Katherine Mansfield and the Russians: Tolstoy, Turgenev, Nabokov, and Chekhov; as well as her friendship with Irish writer William Trevor. A sense of trajectory emerges as the book progresses and narrative elements begin to replace the initial chapter’s serial remembered moments and introduction of themes. Alienated solitude gives way to a more social present (although the book’s final paragraph remains unusually ambiguous).

In life we seek like-minded people despite – or because of – the limit of knowing and understanding. We do so to feel less lonely, though it brings a different kind of loneliness

Discussion of writers is, of course, disguised autobiography, as Li herself recognises. “I was aware that my obsession with [Mansfield and Larkin] reflected what I resent in myself: seclusion, self-deception, and above all the need – the neediness – to find shelter from one’s uncertain self in other lives.” Her examinations of Nabokov’s decision to write in English – not Russian – Larkin’s self-protective passivity, Mansfield’s anxiety about her work and Woolf’s competitiveness all become parables by which the reader may better understand the author.