How to read North Korea: 10 books that take you inside the hermit kingdom

From true stories such as Shin Dong-hyuk’s miraculous escape from Camp 14 to a graphic novel inspired by a Canadian cartoonist’s brief stay, these powerful books offer insight into one of the world’s most isolated states

North Korea – or the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, if you prefer – has been a growing source of fascination for the rest of the world since 1948, when “supreme leader” Kim Il-sung began fashioning the “workers’ state” into what’s now widely described as the hermit kingdom.

Dynastic rule has continued with his son, Kim Jong-il, and grandson, Kim Jong-un, who have also perpetuated the tradition of thumbing the national nose at the wider world in general and the United States, in particular.

With the nation again embroiled in geopolitical brinkmanship, Post Magazine picks 10 essential books for a better understanding of North Korea.

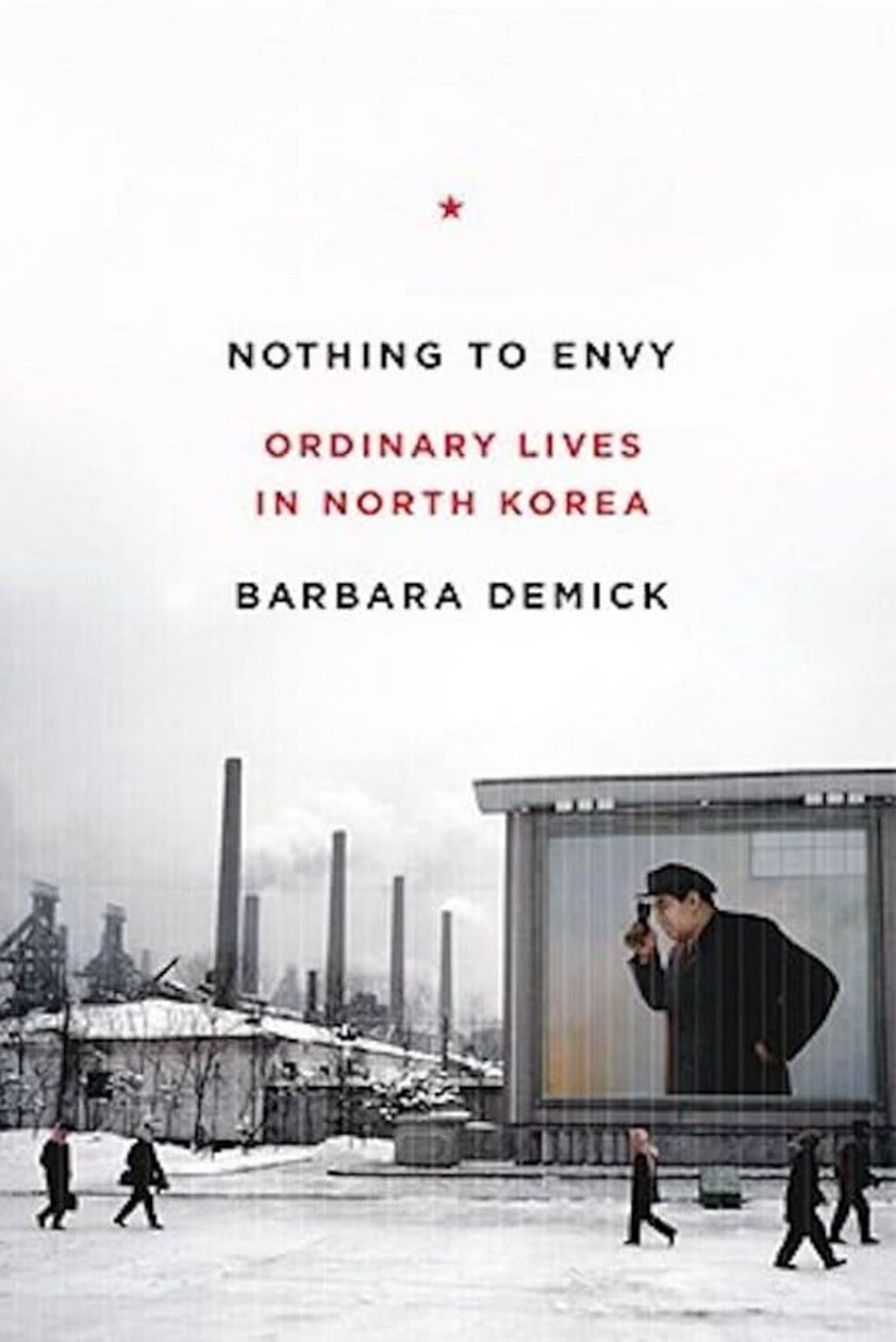

Arguably the best-known book about North Korea, this finalist for the United States’ National Book Award and winner of Britain’s Samuel Johnson Prize profiles six ordinary North Koreans trying to escape from the provincial town of Chongjin.

Demick, then a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, fuses exhaustive research (she interviewed more than 100 defectors) and a novelist’s eye for character. Starting with the famine of the 1990s and ending with the ruinous currency reform of 2009, Demick traces the growing disillusion of, among others, a doctor, a housewife and her daughter, Oak-Hee. “[Kim Jong-il] has turned you all into idiots,” Oak-Hee tells her mother.