Review | China’s draconian education system under spotlight in Little Soldiers – book review

When Lenora Chu’s son came home from his Shanghai kindergarten with tales of harsh treatment, the American journalist threw herself into understanding what makes Chinese schools tick, as she recounts in this rollicking read

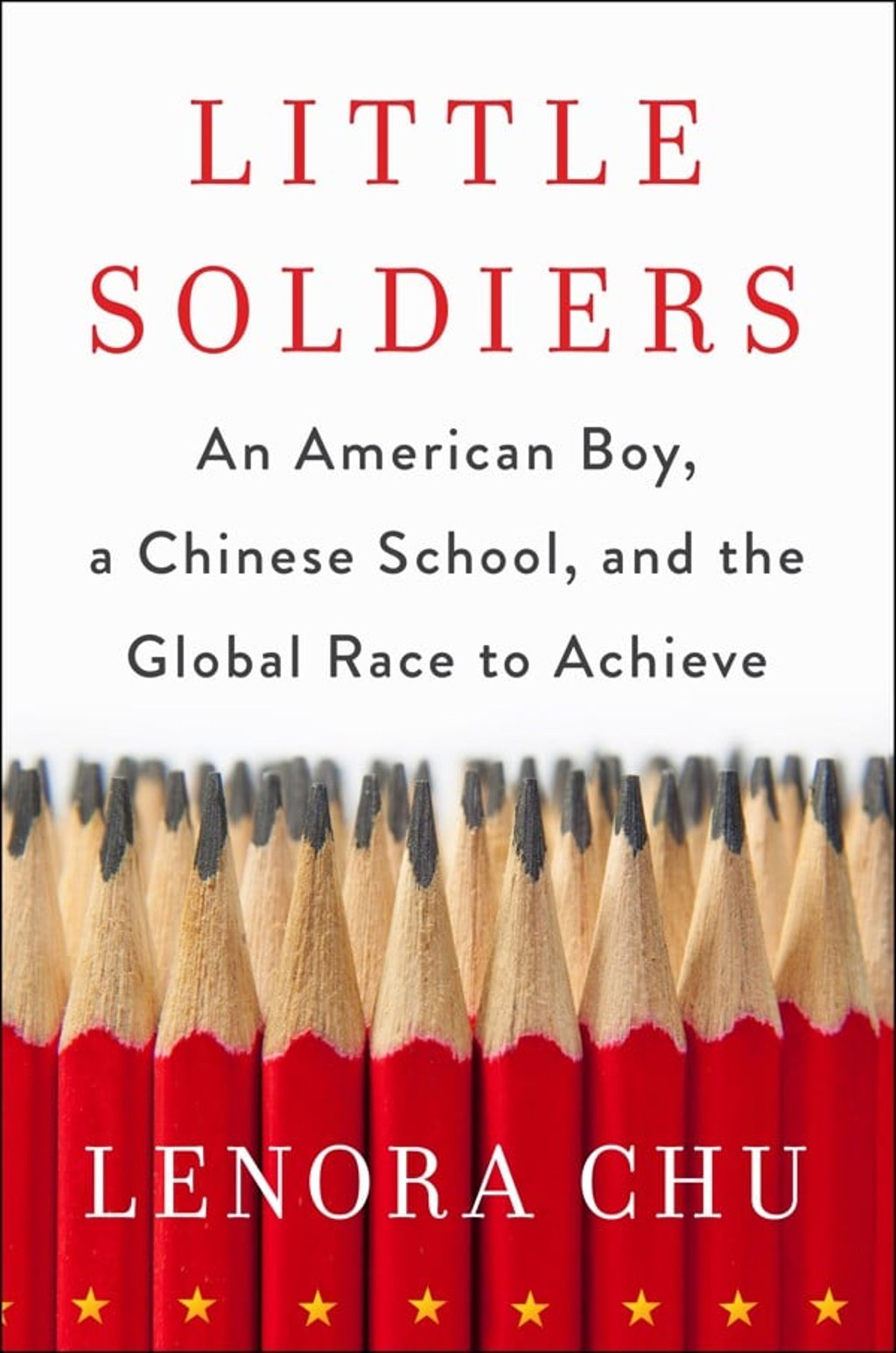

Little Soldiers

by Lenora Chu

Harper

“There is a little man who resides inside the head of every Chinese man and woman, whether they know it or not,” Lenora Chu writes in her new book, Little Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School, and the Global Race to Achieve. “He governs how they find their mates, what they look for in jobs, how they treat their parents, and how they educate their children.” That little man is, of course, Confucius.

Perhaps it was the resounding influence of the ancient philosopher that convinced Chu, an American journalist based in Shanghai with her husband, National Public Radio’s Shanghai correspondent Rob Schmitz, to enrol her toddler son, Rainey, not in one of the city’s international schools – a predictable choice for many of Shanghai’s expat couples – but in a Chinese kindergarten considered a super-school.

Chu realised quickly that the teachers were not exactly followers of the creative and compassionate Waldorf method. After his second day, Rainey came home and told her that he had been force fed egg – which he detested. When he wailed and spat it out, his teacher put it back in his mouth – four times – until he finally swallowed.

A few days later, the teacher was not only unrepentant but offended. She called Chu over and sternly rebuked her, saying, “I want you to refrain from questioning my methods in front of Rainey [...] In front of the children, you should say, ‘Teacher is right, and Mom will do things the same way.’”