2017’s best books: big-name writers returned to spotlight, and Liu Xiaobo’s untimely death casts a shadow

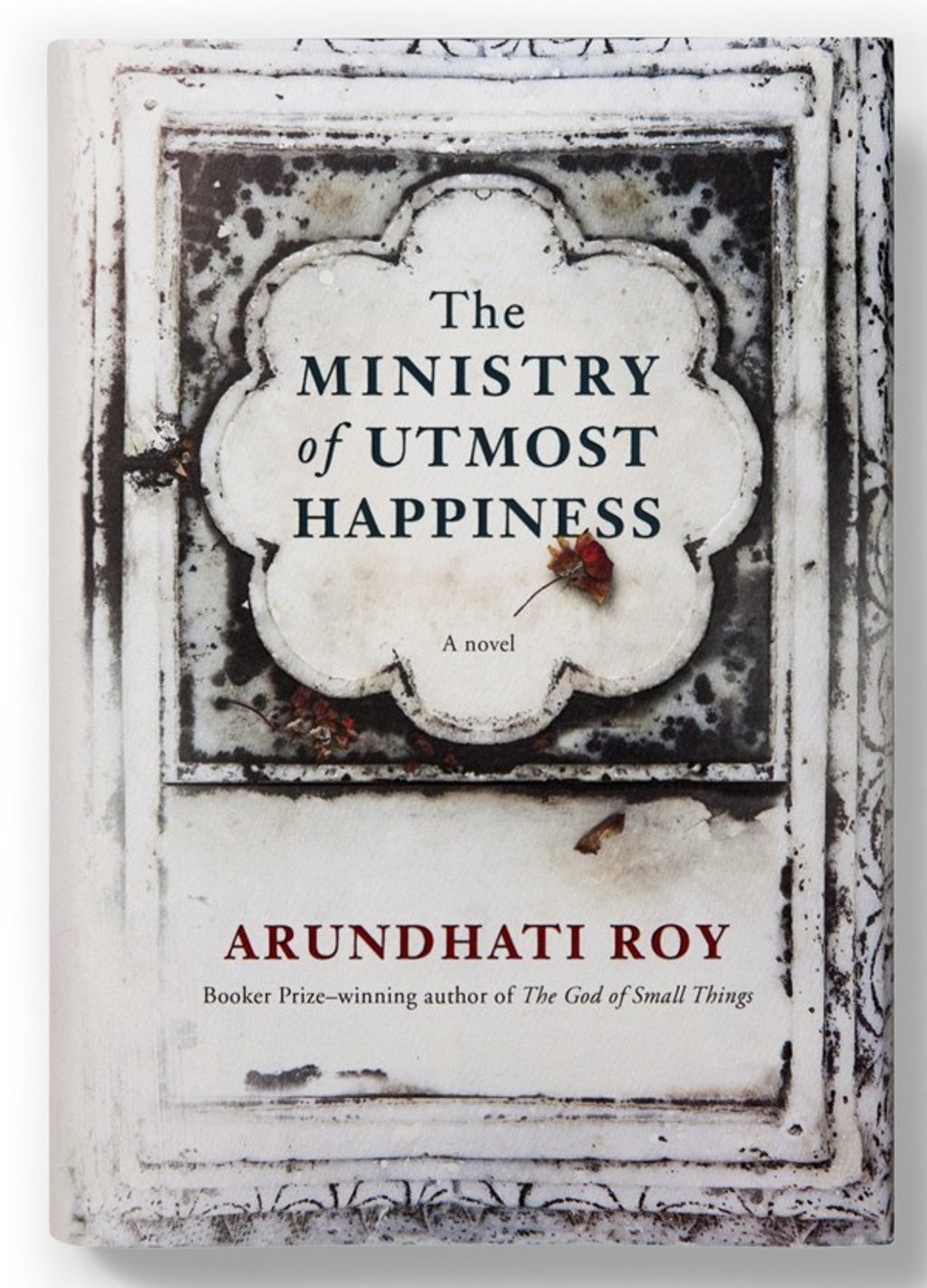

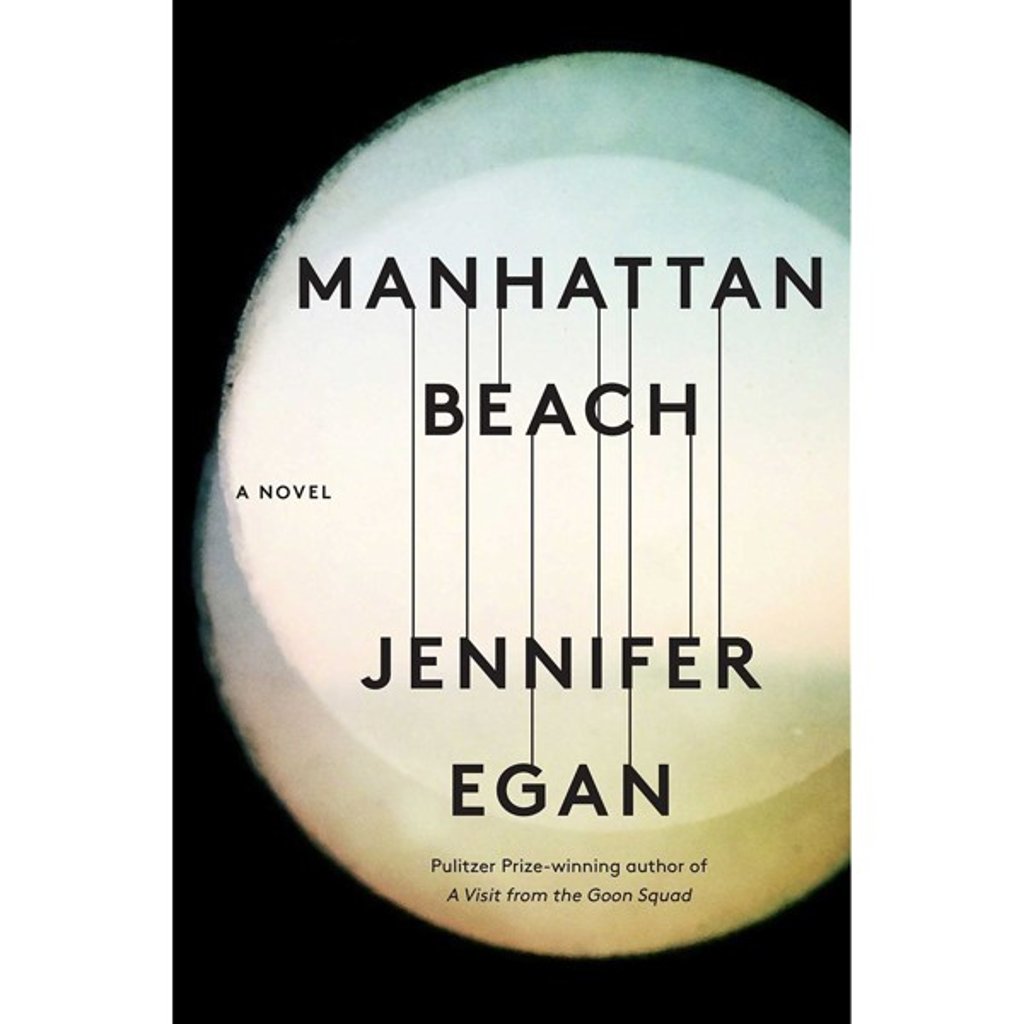

This year saw long-awaited new works of fiction from veterans Arundhati Roy, Salman Rushdie and Philip Pullman, and Kazuo Ishiguro picked up the Nobel Prize in Literature; two Asian writers penned our best novels of 2017

It can be argued that 2017 was a good, if not great, year for literature. No single author or work dominated international bestseller lists or review pages in the way that J.K. Rowling, Dan Brown or Stieg Larsson, or Twilight, Gone Girl or 50 Shades of Grey, had done previously.

And what was arguably China’s biggest book-related story in the 12 months said less about what was being read than where one might read: the opening in October of the Tianjin Binhai Library. Designed by Dutch architectural firm MVRDV to resemble the human eye, its 37,000 square feet contain 1.2 million books.

“The angles and curves are meant to stimulate different uses of the space, such as reading, walking, meeting and discussing,” explained MVRDV co-founder Winy Maas. “Together they form the ‘eye’ of the building: to see and be seen.”

Making headlines in 2017 were long overdue returns to the spotlight by some literary veterans.