Review | The story of a martyr in Mao’s China: executed and her family billed for the bullet

Lian Xi’s book tells the untold tale of Lin Zhao, a Chinese dissident who showed her contempt for Mao’s regime through letters written in her own blood

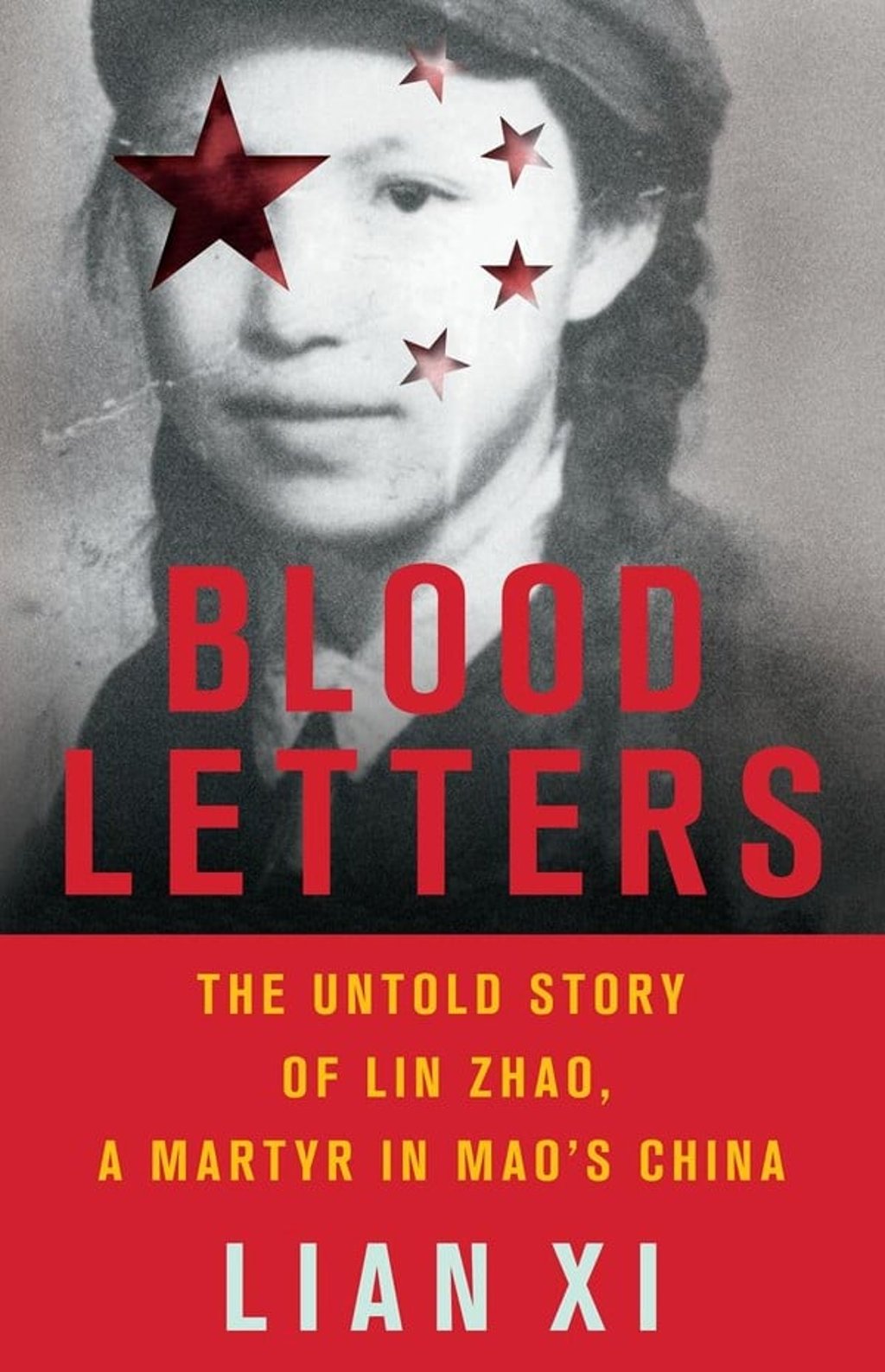

Blood Letters: The Untold Story of Lin Zhao, a Martyr in Mao’s China

by Lian Xi

Basic Books

If Djilas’ book had been published earlier, it may have changed the life of Lin Zhao, a young political activist born Peng Lingzhao who met a tragic end 50 years ago on April 29, during the Cultural Revolution. The enthusiastic young revolutionary joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1948 and spent a decade as a loyal member before being arrested on suspicion of being a rightist, in January 1958.

Djilas’ critique of communist ideology was published the same year that the far-left went on a murderous rampage across China in the name of Mao Zedong’s Anti-Rightist Campaign. As historian Lian Xi recalls in his new book Blood Letters: The Untold Story of Lin Zhao, a Martyr in Mao’s China, the campaign targeted so-called “leading rightists” across the then new communist state. It resulted in hundreds of thousands of intellectuals being killed, jailed or persecuted.

The purge of rightists was part of a cleansing operation across China during the early years of the Cultural Revolution, a decade-long nightmare that saw about 1.5 million people die in an orgy of ideological violence.