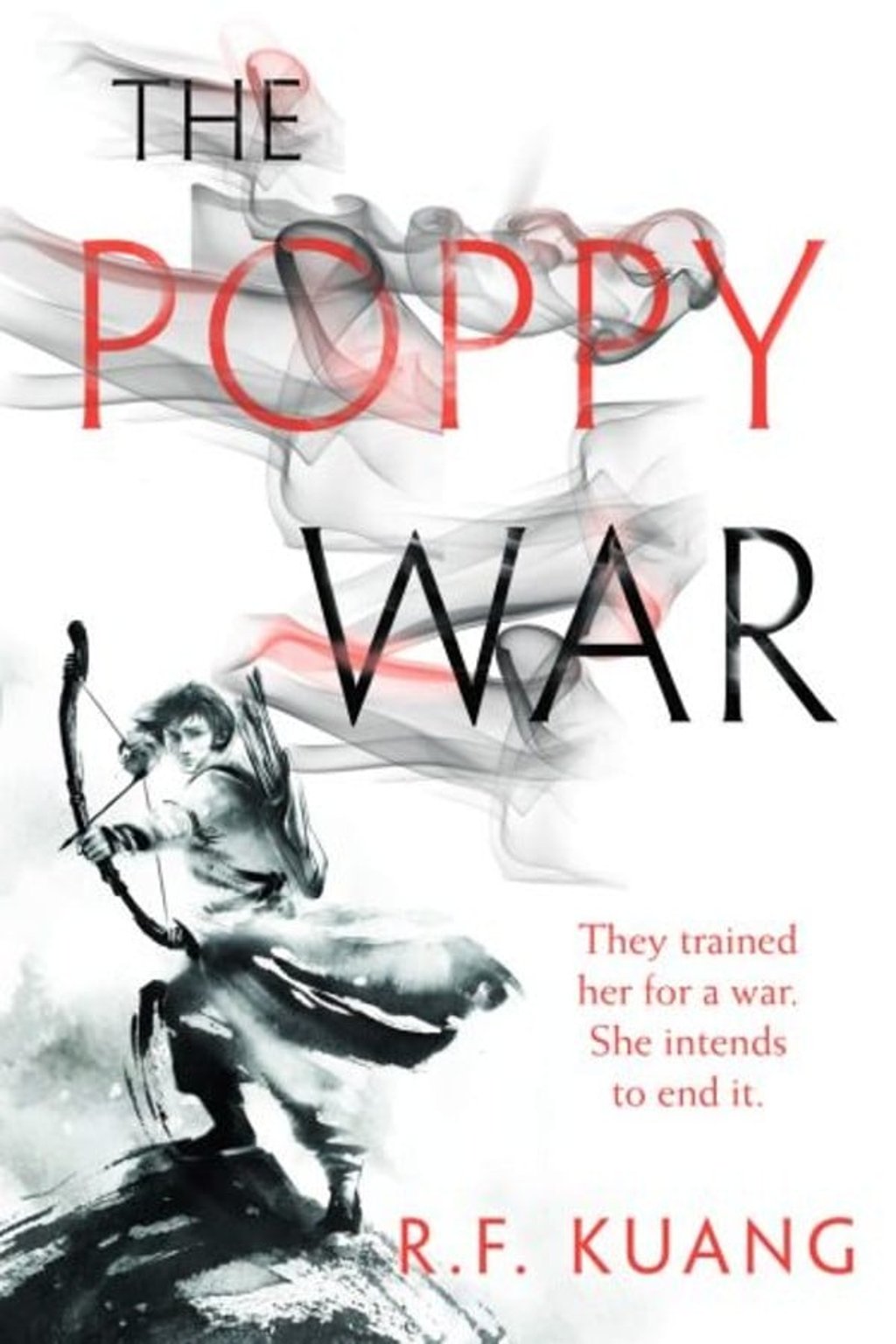

China’s bloody history and Game of Thrones-style fantasy unite in author R.F. Kuang’s debut novel

Described as a ‘revenge fantasy’, The Poppy War’s fictional world is steeped in brutal, historical fact

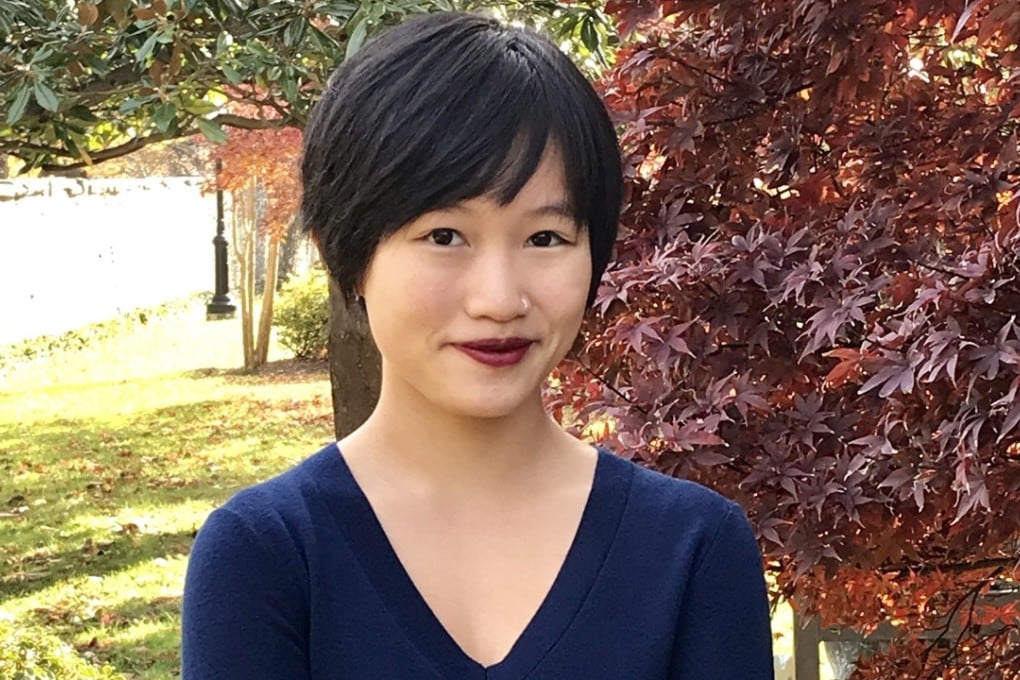

“I just think that novels are really cool,” says 22-year-old R.F. Kuang (the R is for Rebecca, the F remains a mystery). She has just released a very cool first novel of her own, The Poppy War (Harper Voyager), which kick-starts a trilogy boldly mixing 20th-century Chinese history with the country’s ancient past.

Think sci-fi writer Liu Cixin’s Three Body Problem crossed with Game of Throneswith a touch of Star Wars, and you’re not far off. As Kuang puts it, “The most interesting parts of books two and three have been working out the philosophical and ideological differences between the protagonists, but making it make sense in a Song-dynasty fantasy setting.”

It is a remarkable achievement, all the more so because Kuang, who was born in Guangzhou and raised in America, wrote this extensively researched epic while studying at Georgetown University, in Washington. In the autumn, she will begin a master’s degree at Britain’s Cambridge University and plans to write her thesis on an as yet undecided aspect of Chinese military history. Kuang agrees when I say there do not seem to be many female war historians. “I’m not sure why. It’s not like war is an inherently masculine thing.”

We speak during Kuang’s lunch break from her day job, in Colorado. “I am teaching debate camp,” she says. “This year it is ‘Violent revolution is a just response to political oppression’.” The proposition seems tailor-made for Kuang, given that The Poppy War can be read as tracing the roots of China’s own communist revolution.

“The problem is violent revolutions don’t always set up peaceful, democratic governments afterwards. But it’s a two-part question, right? A violent revolution can be justified even if the government that results is not democratic.” This includes China, she adds, “because a lot of things went wrong after 1949”.