10 of the best self-help books to improve your life, diet and home environment

Turn the page on unproductive old ways for a happier, healthier and less cluttered tomorrow

If Help! by the Beatles is your default theme tune, there is probably a self-help, or self-improvement, book for you.

Want to boost your brain power and enhance your happiness, survive a dysfunctional family, be lucky in love, make heaps of cash or beat depression? Just open the right book. The field is so extensive that a single volume can sometimes constitute its own subgenre, but general themes are often discernible.

The 10 recently released books here align vaguely, or obviously, with veganism, anxiety, and minimalism and decluttering. Or: eat, smile, chuck out your junk. If your problems prove too intractable, you might still need professional advice. In the meantime, help yourself.

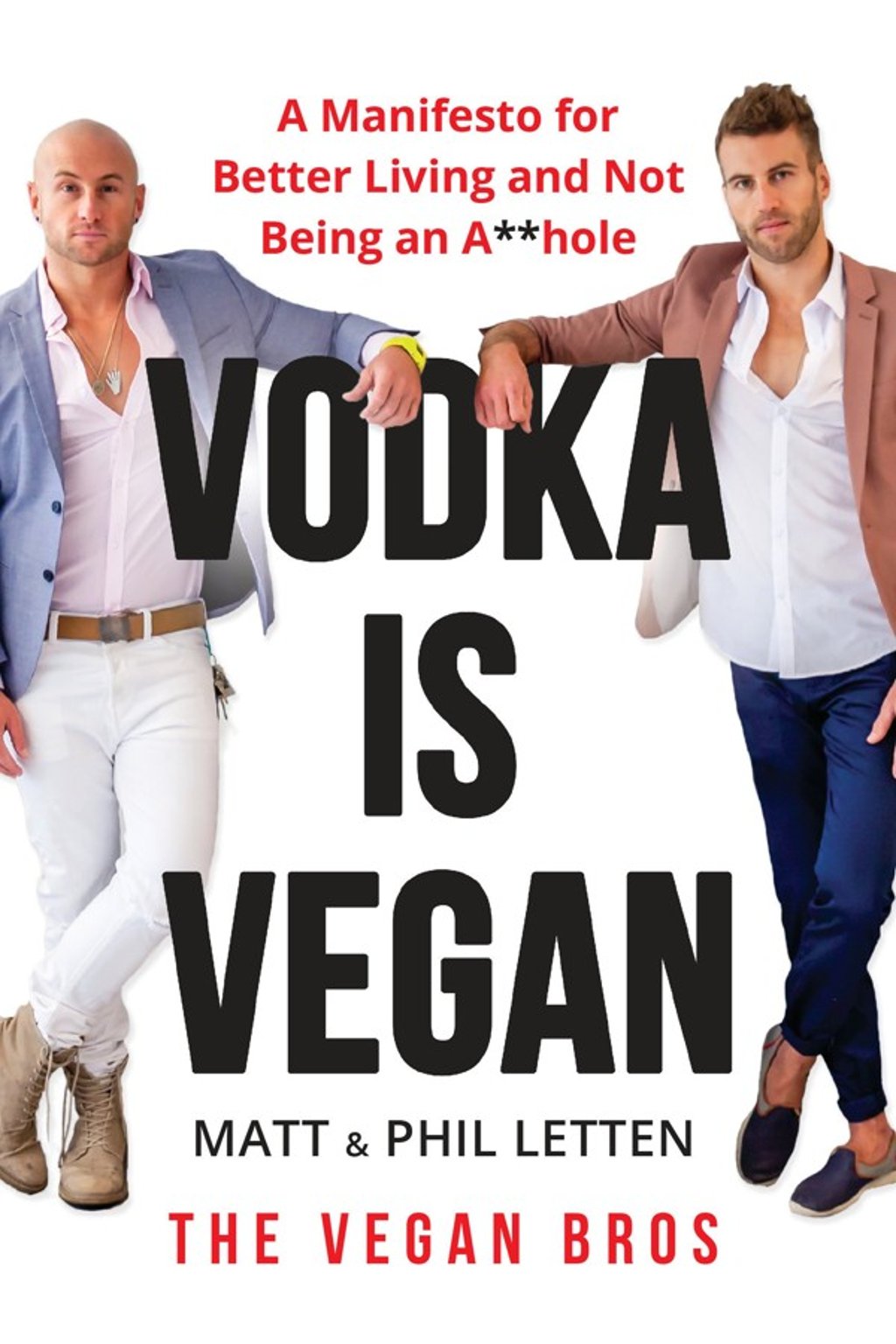

Vodka is Vegan

Their manifesto also explains that not all vegans are “a**holes [...] outspoken about their veganity”. Other “amazing, compelling reasons to eat vegan” include not having to join “some weird cult” or look like a “pencil-necked hipster”. But approachability aside, they pull zero punches in describing standard meat industry secrets, which include ripping “the testicles off conscious piglets without anaesthetic” and “cows having their throats slit while fully conscious and screaming”. Burger, anyone?

Little Panic