‘It wasn’t a sad camp’: Hong Kong POW diaries tell of hope and hardship

Interest in her war stories from grandchildren made British stenographer Barbara Anslow think they deserved a wider audience, but publishers initially weren’t interested in her memories of Stanley Internment Camp, where she, her mother and sisters and future husband were prisoners of war

It’s hard to know which is more remarkable – Barbara Anslow’s story, or the way it’s been published. The 99-year-old British woman is one of the diminishing number of survivors of Stanley Internment Camp, where she was held for more than three- and-a-half years during Japan’s occupation of Hong Kong during the second world war.

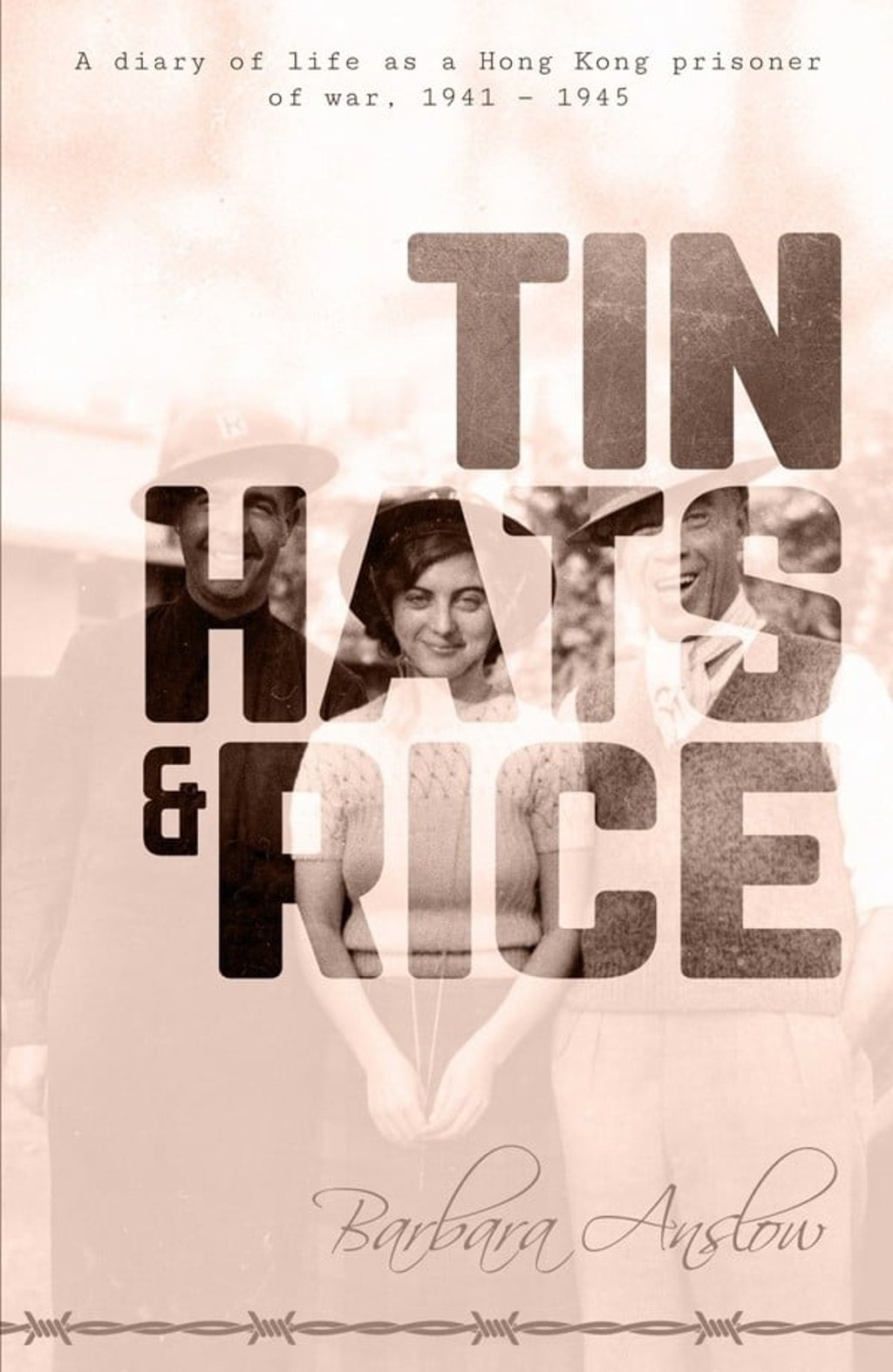

Anslow wrote a detailed diary of her experiences, starting in late 1941 and finishing after the war ended – which has finally been published in book form as Tin Hats and Rice, three-quarters of a century after the events it recounts.

Born in Scotland in 1918 – she will turn 100 on December 1 – Anslow, née Redwood, moved to Hong Kong with her parents and two sisters in 1938, working as a government stenographer. As war approached she was supposed to be evacuated to Australia with her mother and sisters but got only as far as Manila before receiving the news that her father had died, and returning.

Anslow was living in Happy Valley when the Japanese invaded, and was transferred to Stanley with more than 2,000 others. She met her future husband, Frank, there, although they weren’t romantically involved until after the war. Anslow went back to Britain after her release, in 1945, but soon returned to Hong Kong, finally leaving again in 1959.

“First of all, I tried sending extracts to some publishers, but they weren’t interested, so I thought the diary would just be something for my family,” she says. “Then I got an email from David Bellis, at Gwulo.