Review | The Fall of Gondolin, Tolkien’s posthumous Middle Earth prequel is driven by ‘magic and destiny’

Written before both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, The Fall of Gondolin – the last of the much-loved fantasy author’s three ‘Great Tales’ – has finally made it into print

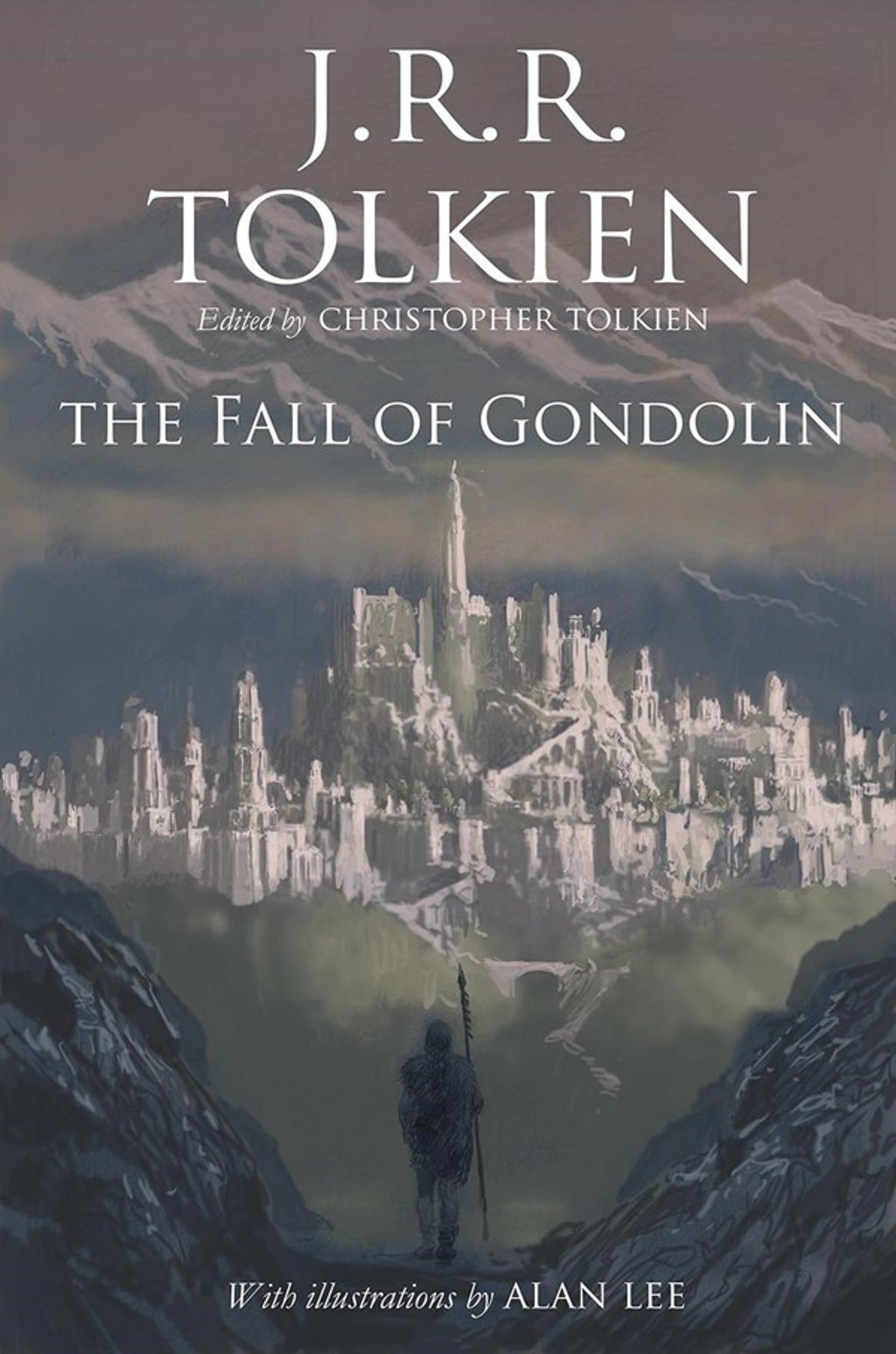

The Fall of Gondolin

By J.R.R. Tolkien

Harper Collins

You cannot move these days for ever-expanding big-budget fantasy franchises. Star Wars, Harry Potter and Marvel have all pushed beyond their original markets, and now can be found in cinemas, bookshops and video games, not to mention supermarkets, where you can buy branded T-shirts, lunchboxes, pencil sharpeners and more.

Following the surprisingly wild adventures of diffident Bilbo Baggins, who joins a band of dwarves on their quest to seize treasure stolen by the dragon Smaug, the novel became a global phenomenon but was hailed largely as a work for children. This success pushed Tolkien’s publishers to request – or probably demand – a sequel, and Tolkien delivered The Lord of the Rings 12 years later. Divided into three separate books (The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers and The Return of the King), the winding story required almost 10,000 manuscript pages and 455,125 final words. The central threads – the quest of two hobbits to destroy a terrible ring of power, and of one man to reclaim his lost throne – were woven into a vast tapestry of mythology, geography, politics, language and substories.

The resurgence of Tolkien mania has seen the release of a few additions to the writer’s vast narrative network: The Children of Húrin (2007), The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún (2009) and Beren and Lúthien (2017). All required the editorial intervention of Tolkien’s son, Christopher, to spruce up the text.