Review | Tale of four real-life escapees from 1949 Shanghai fails to captivate

- Helen Zia’s Last Boat Out of China is burdened by too much information, while the characters’ personal details seem tame compared with backdrop of war

- We follow police chief’s son Benny; twice abandoned Bing; Ho, the son of landowners; and Annuo, daughter of a Nationalist soldier

Last Boat Out of Shanghai

by Helen Zia

Ballantine Books

Historical fiction is a hybrid art form requiring a skilful fusion of narrative and research. When done well – as, for example, in James Clavell’s superb Noble House (1981) or War and Peace and A Tale of Two Cities – the results can be thrilling and informative. But when done badly, with the author failing to combine background and story, the result can be an unfulfilling mixture of half-digested factoids and characters that don’t offer insight into their motives.

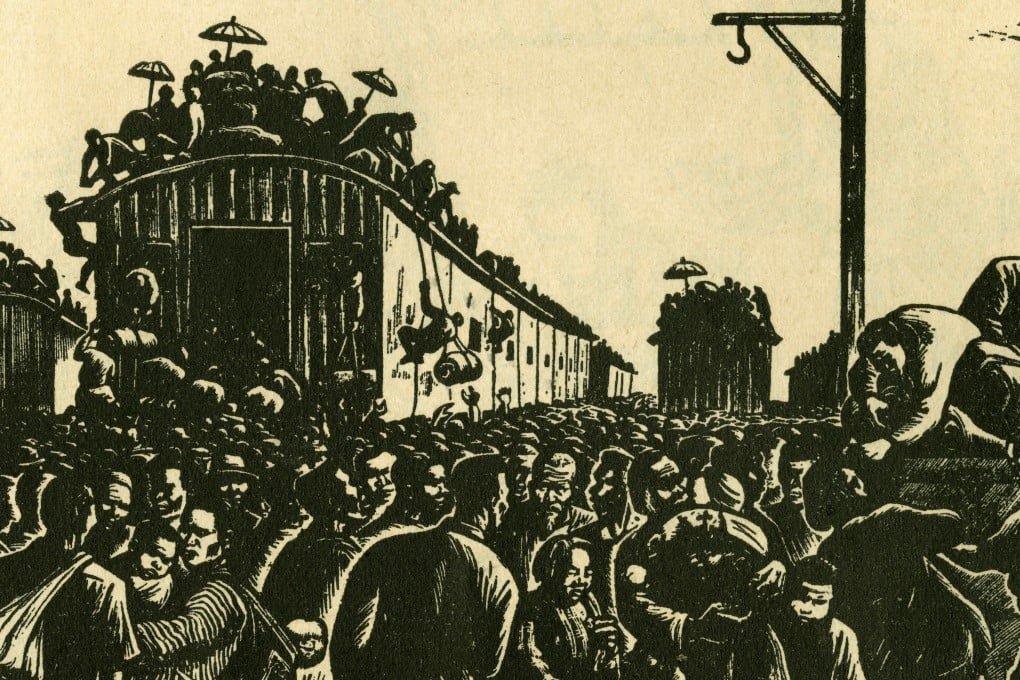

Helen Zia’s Last Boat Out of Shanghai fits into this spectrum somewhere towards the less effective end. The novel does many things well: Zia has conducted substantial research (the endnotes run to 17 pages); its evocation of pre-war, wartime and revolutionary China feels true to life; and the fears, hopes and anxieties of the characters are expressed humanely. It understands that choices during wartime can often be between bad and worse. And when the action hots up, it can be a fast-paced, dramatic read. The choice of topic is inspired, with the title suggesting end-of-days panic and a dissolution of the old order, and that alone should guarantee substantial interest in the book.

Last Boat Out of Shanghai follows four individuals who flee the city in the final days of Nationalist rule and find new lives in the New World and elsewhere. All real people, still living, who were children during the Communist takeover, making their experiences rather homogenous. They are Benny (from a wealthy Shanghai family, his father an accountant and auxiliary police officer before rising to become police commissioner); Ho (raised in Changshu, in Jiangsu province, and from a family of landowners, though he dreams of becoming an engineer); Bing (born in Changzhou, in Jiangsu, whose father takes her to a shopkeeper in Suzhou and heads out of the door without saying goodbye); and Annuo (whose mother is a doctor treating victims of Japanese bombing in Shanghai and her father a Nationalist soldier).

Each is given separate chapters within the novel, which is divided into four sections: “The Drumbeat of War”; “Childhood Under Siege”; “Exodus”; and “War’s Long Shadow”.

While this approach injects variety into the book, it makes the opening section slow going. The reader does get a firm grounding in the lives and backgrounds of the four, but it’s a grind.