In Gun Island, Indian author Amitav Ghosh explores human response to climate damage

- The New York-based writer’s ninth novel lays bare mankind’s failure to process the new realities of a changed environment

- The book also touches on an earlier time of folklore and the fantastic, when life moved much slower

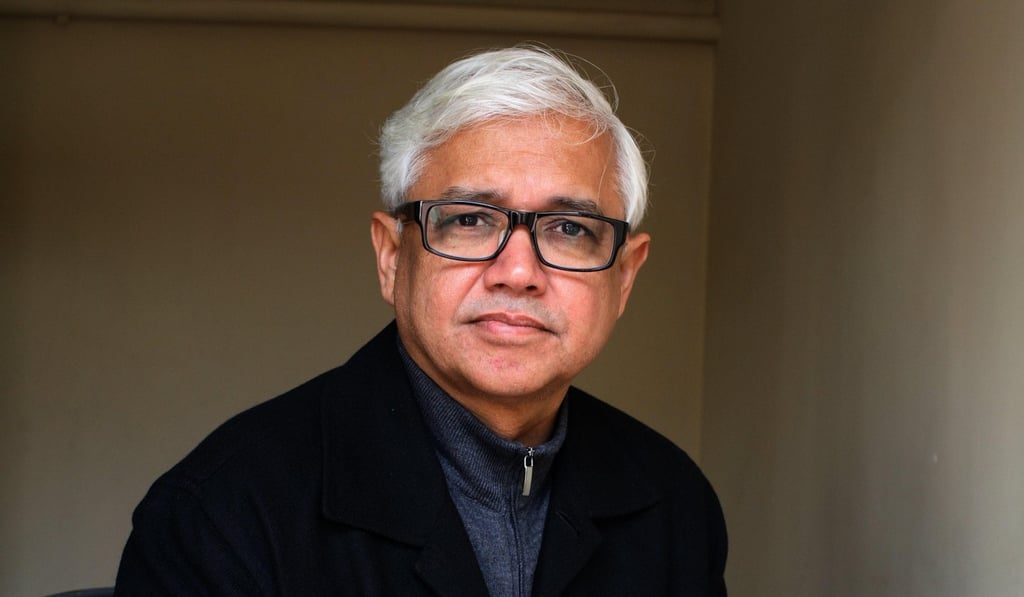

“Anyone who believes in human progress is delusional,” author Amitav Ghosh tells a rapt audience gathered among the old bookcases and oil paintings of the Shaw Library, at the London School of Economics. “Climate change is the biggest threat facing humanity. Our whole paradigm is to blame: wanting, owning, ‘developing’, ‘progressing’.”

Ghosh’s voice, soft and lilting, feels more suited to telling stories of adventures past than of impending apocalypse, but his measured tone makes the message all the more powerful. Discursive, rather than didactic, he invites the audience to engage with this most pressing of problems – and try to understand why our response to it has been so inadequate.

His 2004 novel The Hungry Tide is based in his beloved Sundarbans, a delicate ecosystem of mangroves and mud in the Bay of Bengal that has already been severely altered by climatic disturbance. And his book of essays, The Great Derangement (2016), explores why we are unable to grasp the scale and violence of climate change.

Now, Ghosh has released his ninth novel, Gun Island, which could be described as fictionalised musings on climate change. But dry and depressing this novel is not – far from it, in fact; the book is as readable and enjoyable as his other works, and even more likely to surprise.