Review | City on Fire revisits Hong Kong’s 2019 protests and asks ‘what next’?

- Lawyer Antony Dapiran gives voice to both sides in what publisher describes as an essential guide to ‘fight for the very soul of the city’

- He also explores a long history of dissent, including the 1967 riots and the 2014 ‘umbrella movement’

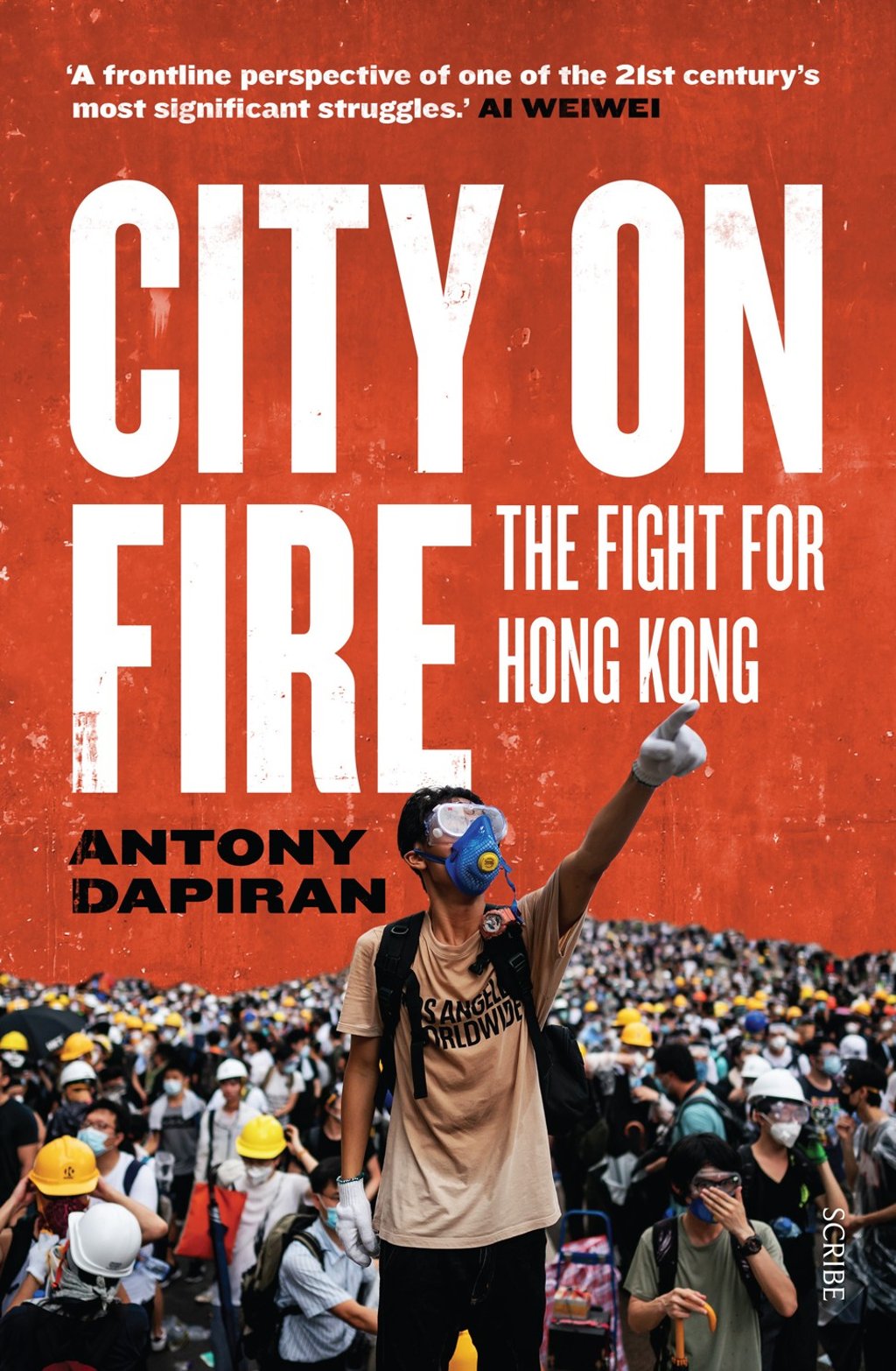

City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong, by Antony Dapiran, Scribe, 4.5/5 stars

City on Fire lives up to its publisher’s promise of providing an essential guide to the Hong Kong protests. Its author – writer, lawyer and long-term Hong Kong resident Antony Dapiran – is renowned as a clear-eyed observer of the city’s politics. His 109-page book, City of Protest: A Recent History of Dissent in Hong Kong (2017), was lauded for its incisive analysis of the “umbrella movement” and the emotions that propelled it.

But City on Fire is more than a mere extension of this history of dissent. It illuminates every phase, trigger and turning point, skirmish and tactic in what began as a protest against an extradition bill but became “a fight for the very soul of the city”.

“And what,” he asks late in the book, “is the soul of a place, but its identity?”

The prologue sets the tone and haunts the ensuing 20 chapters. Devoted entirely to a study of tear gas, it would be tempting to skip it – given its use in Hong Kong has been widely covered – were it not for its urgent, almost poetic potency. At the end of the prologue, Dapiran writes: “Hongkongers have a new saying, a new aspect to their identity: ‘You’re not a real Hongkonger if you haven’t tasted tear gas.’”