Review | Memoir of 15 years at Studio Ghibli, Japanese animation studio, is big on detail but lacking in the magic of the movies

- Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man, by Steve Alpert, tells of his time at the Japanese animation studio

- Part business memoir and part confessional about life as a foreigner in Japan, the American’s book fails to fully deliver on either

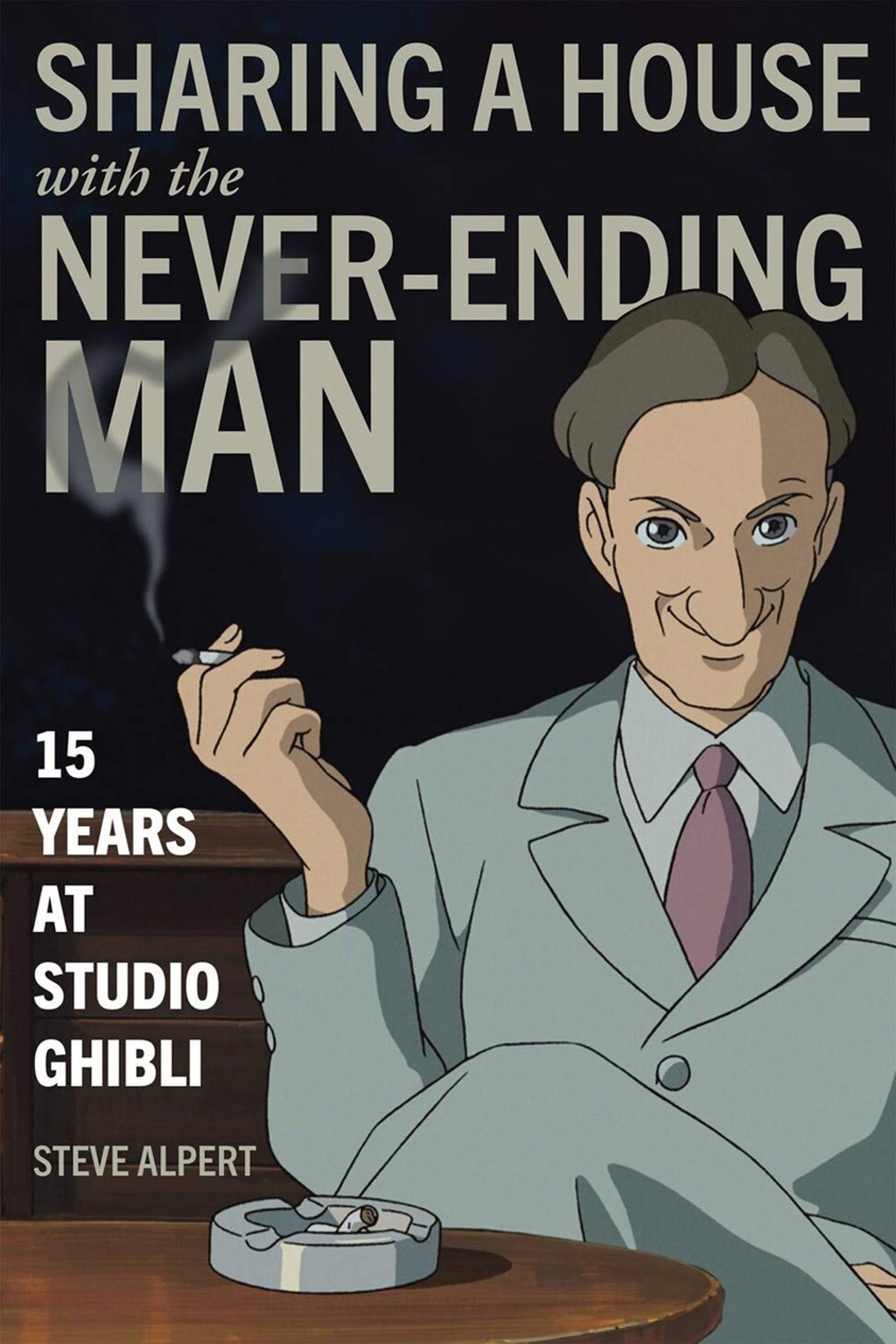

Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man: 15 Years at Studio Ghibli by Steve Alpert, Stone Bridge Press, 2/5 stars

Once a week the influential co-founder of Japanese animation giant Studio Ghibli would sit and draw at a modest wooden desk, to show fans how his films were made. Massive lines and crowds quickly formed to see Miyazaki; museum staff struggled to maintain order.

His appearances were eventually scrapped, but the desk remains at the museum today, cluttered with palettes of gouache daubs and half-etched drafts, as if the artist had just stepped away and would be back any second.

Such is the enigmatic aura of Miyazaki and his many creations under Studio Ghibli, the once-humble Japanese animation company that exploded onto the international stage with Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), My Neighbour Totoro (1988), Princess Mononoke (1997) and the Oscar-winning Spirited Away (2001).