Review | How Hello Kitty and other Japanese pop culture icons conquered the world

Japan may no longer be ahead of the creative curve, writes Matt Alt in his new book, Pure Invention, but its influence on everything from comics to computer games has turned us all a little bit Japanese

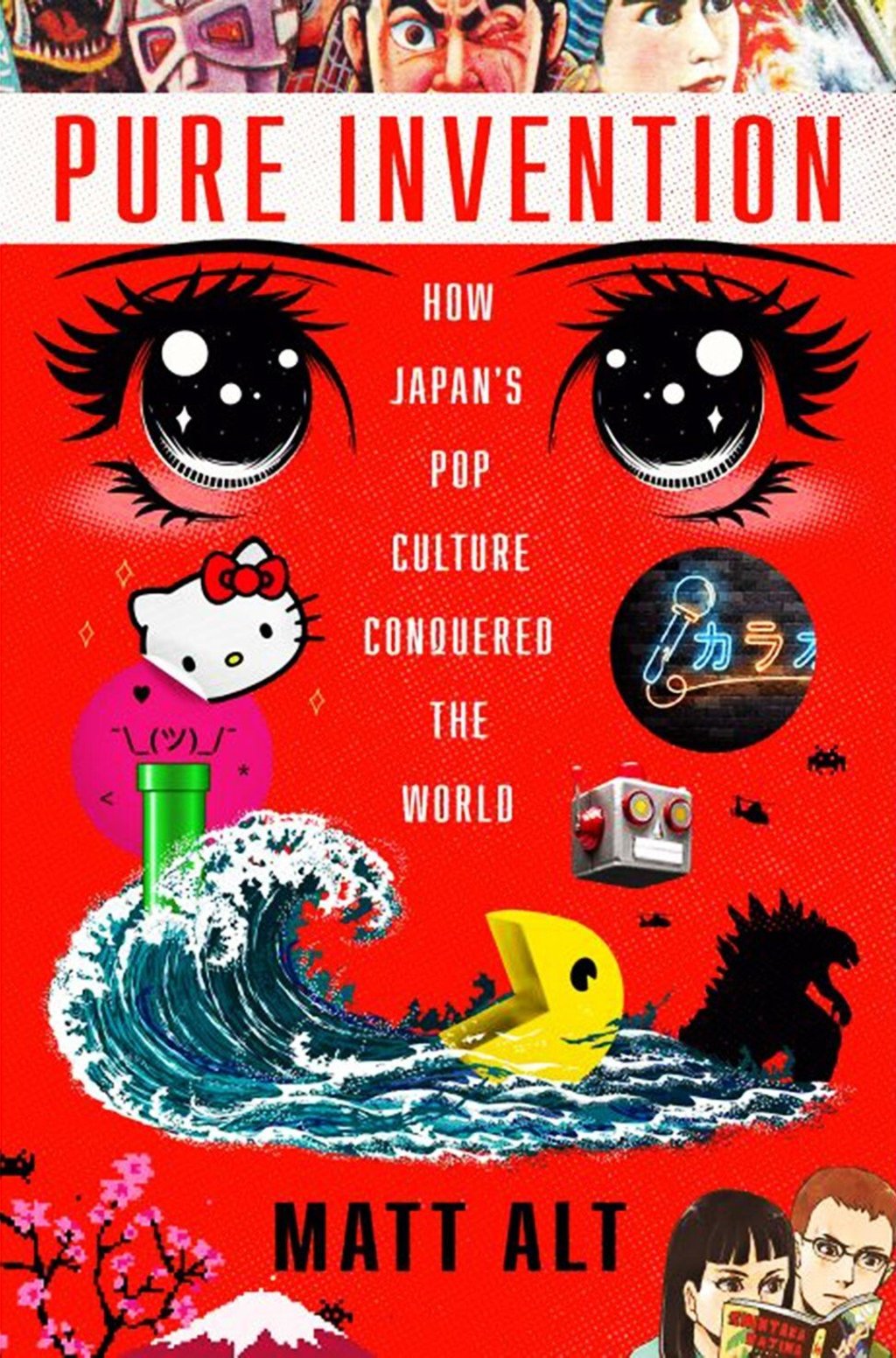

Pure Invention: How Japan’s Pop Culture Conquered the World by Matt Alt, Crown. 4.5/5 stars

You can almost hear the teeth gnashing that would have accompanied Nintendo’s decision to release Animal Crossing: New Horizons on March 20, days before the Tokyo Olympic Games were cancelled. But the height of the pandemic was the perfect time to engage gamers around the world. In just 12 days, 11.77 million copies were sold, allowing a captive audience the size of Wuhan’s population to visit the self-built, virtual islands inhabited, as Matt Alt writes, “by bobbleheaded kawaii animal characters”.

So it is with Alt’s Pure Invention, a classic in the making that traces the victorious arc of Japan’s pop culture since the 1960s. It feels like the right juncture to be reading about this soft-power triumph, even though the country is no longer ahead of the curve, according to the author.

To help us understand why Japanese fantasies were embraced by the rest of the developed world – which has caught up creatively – Alt takes us back to the pioneers, their products and significant periods of innovation. After World War II, he explains, Japan enriched itself by selling the automobiles, appliances and sundries we needed. “But it made itself loved by selling us things we wanted.”

In conquering the world, Japan’s pop culture also entered English usage, making permanent fixtures of words such as anime, manga, karaoke and emoji. We are equally at ease with superheroes Ultraman, Sailor Moon and Mighty Atom (Astro Boy to Westerners). Ditto arcade games Space Invaders and Pac-Man, and lest we forget, Tamagotchi, the digital creature that relied on our care to survive.

With truckloads of genius on hand, Pure Invention steers us down memory lane, reminding us who we were when, for instance, The Walkman claimed our ears, Totoro our emotions and Pokemon our time and money.