Jane Fonda is willing to get arrested to fight climate change – what can you do?

In her book What Can I Do? the American actor uses her celebrity to highlight the climate crisis and call armchair activists to action. Meanwhile The Planter of Modern Life and World of Wonders examine the environment and our relationship to it in different, but no less important, ways

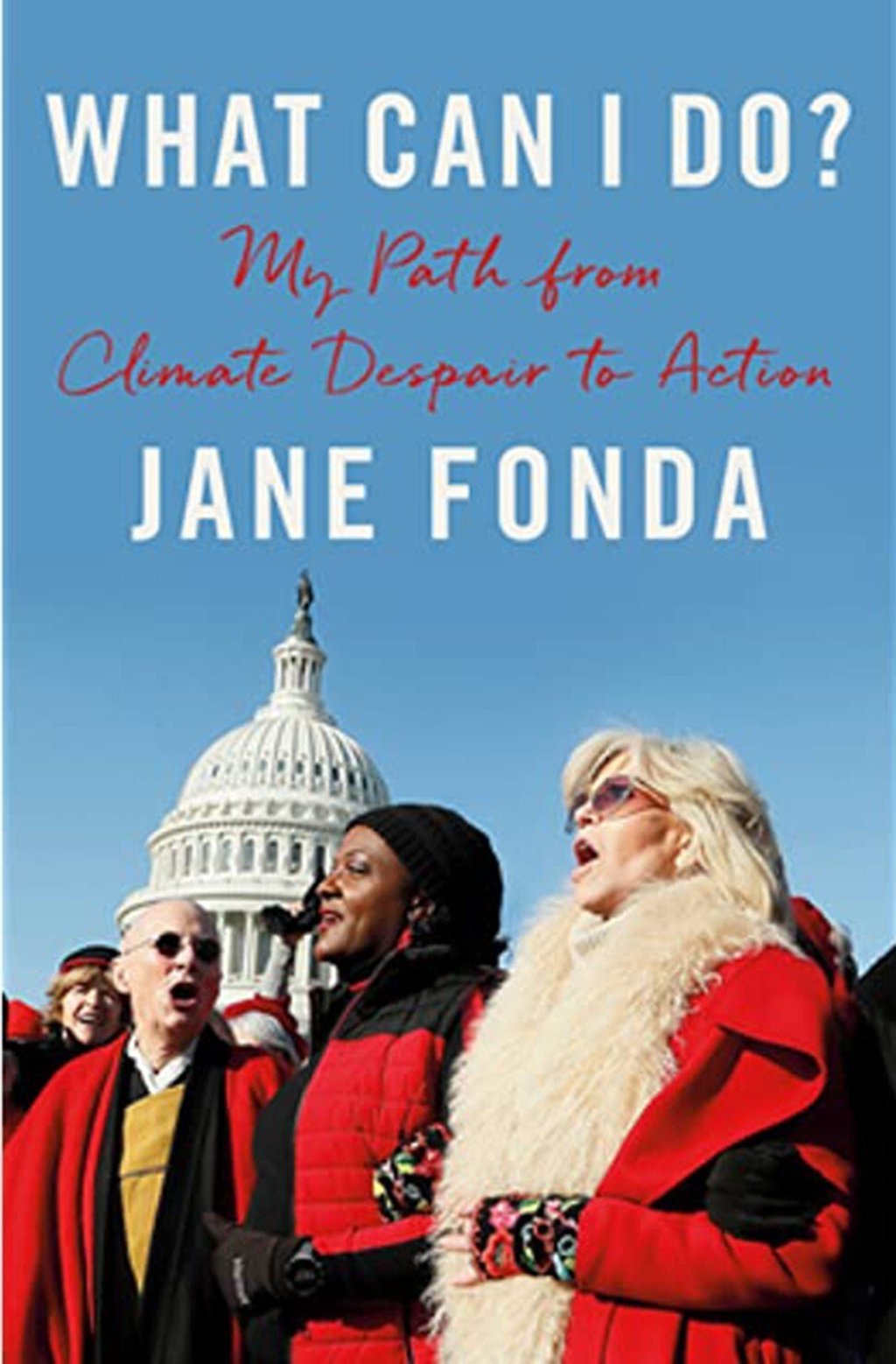

What Can I Do? by Jane Fonda, Penguin Press

Jane Fonda, it turns out, is both Grace and Frankie, the hit sitcom about diametrically opposite best friends: one is coiffed and confident (Fonda); the other a freewheeling tree-hugger whose moral compass remains stuck at trouble (Lily Tomlin). That’s not to trivialise Fonda’s latest book, an instructive volume aimed at levering armchair environmentalists out of their comfort zones.

Despite her infamous “Hanoi Jane” activism, she writes, “‘Fire Drill Fridays’ were my first (conscious) experience with civil disobedience.” Born of Greta Thunberg’s call to act like “our house is on fire”, the weekly protests saw the actor descend on Washington’s Capitol Hilllast year to demand legislative passage of the Green New Deal. Teach-ins at the events allow Fonda to share the opinions of experts before introducing practical What Can I Do? sections.

On the subject of throwaway living, the 82-year-old reminds us she was born “20 or more years before plastic was common in American households”. She suggests demanding bans on unnecessary plastic at schools and workplaces and, ultimately, reducing the availability of fossil fuels, chemicals from which 99 per cent of plastics are produced.

For press coverage, Fonda corralled Hollywood stars, including Tomlin and other Grace and Frankie collaborators, most of whom were only too happy to be arrested to make the headlines. A serial offender, Fonda had this to say to a reporter asking why she was willingly going to jail: “To get you to cover climate.”

The Planter of Modern Life by Stephen Heyman, WW Norton & Company