Review | Three books on privacy in the digital age – if our lives are lived publicly online, what remains personal?

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, by Shoshana Zuboff, explores how our data is used for corporate profit, Sarah E. Igo’s The Known Citizen looks at Americans’ perception of privacy, and The Lost Family, by Libby Copeland, studies the ethics of genetic testing

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff, Profile Books

In the digital sphere, the cliché runs, if you didn’t pay for it, you are the product. But that’s not quite correct. In her provocative book about “surveillance capitalism”, Shoshana Zuboff compares tech platforms such as Google and Facebook to elephant poachers and says we are the carcass. “The ‘product’ derives from the surplus that is ripped from your life.”

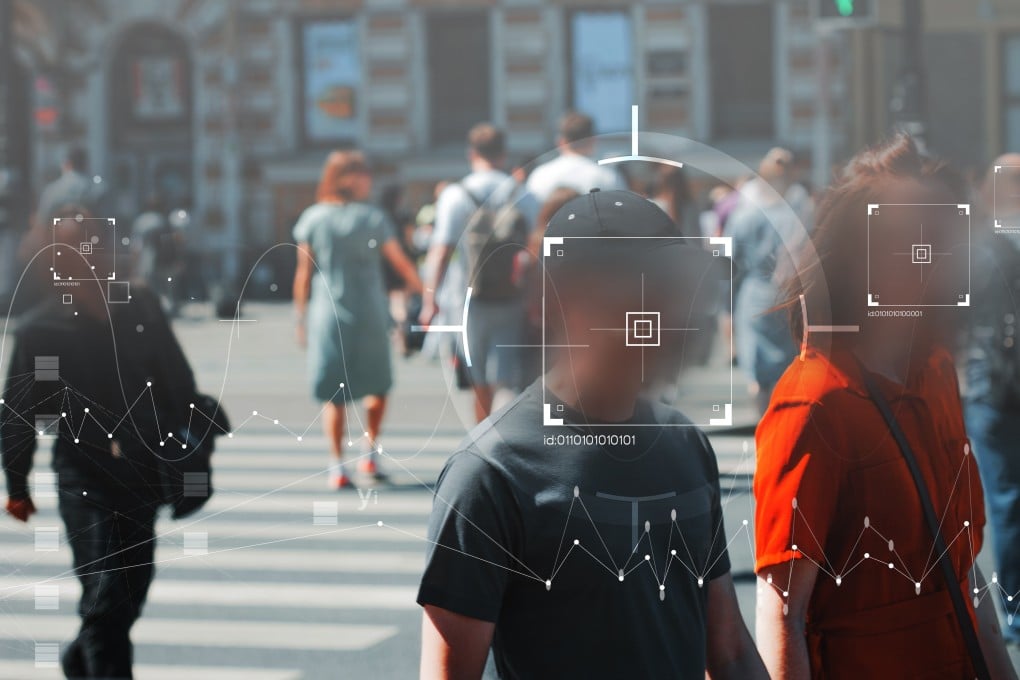

The author explains that surveillance capitalism is a new economic order that relies on the theft of our private experiences for raw data sold to businesses. These companies then create “prediction products” anticipating how we will act. In what she calls behavioural futures markets, the winners are the surveillance capitalists who feed on “digital exhaust” – jargon for leftovers – that can be recycled for profit.

To map its beginnings the author returns to the dotcom bubble, when Google’s prediction products were aimed at targeted advertising. In no time digital infrastructures were being used to provide a God’s eye view of ourselves, leading to automated processes shaping our behaviour for commercial ends. Think Pokémon GO, the hugely successful game app that grew from Google Maps.

This book is a keeper, not least to remind us how it was before and after rogue capitalists staged their coup, assaulting our autonomy so deftly that we didn’t even realise we were being robbed.