The Membranes: Chi Ta-wei’s eerily prescient novel on the terrors of technology available for the first time in English

- Published originally in Taiwan in 1995, The Membranes is set at the bottom of the ocean, where humanity has been forced to retreat because of climate change

- The author’s project is large, as is his vision, and imagines the future like the best of our dystopian meditations

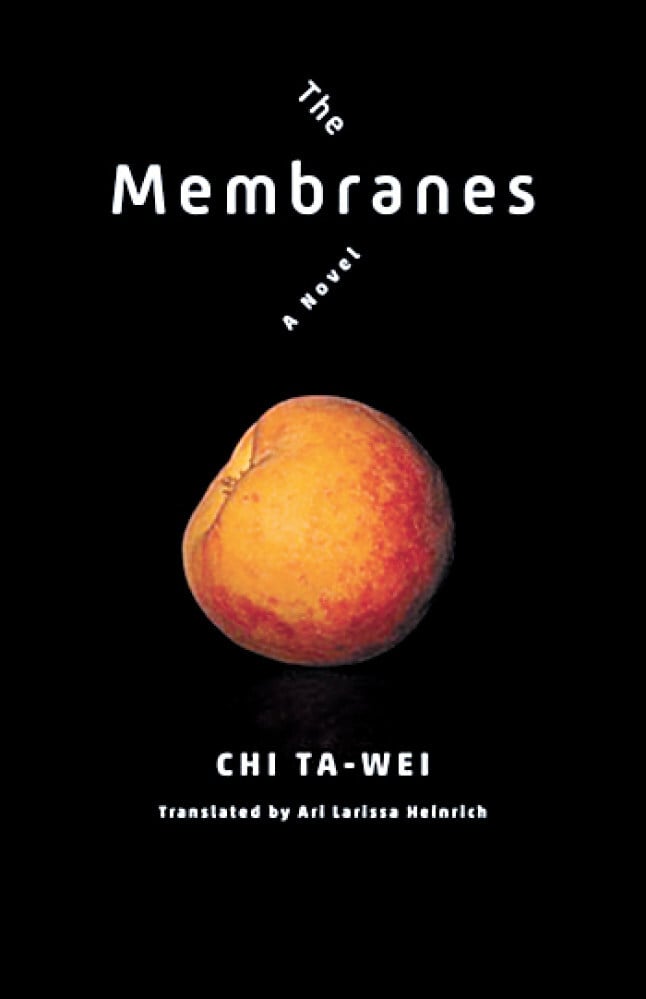

The Membranes by Chi Ta-wei. Columbia University Press

“Shadows, Momo thought. Everywhere.”

Momo is the main character in this philosophically rich, imaginatively potent novel. And her realisation about the “unknowable shadows” of our identity is the chief concern of this eerily prescient work.

Written in Chinese and published originally in Taiwan in 1995, the book is available for the first time in English, translated into impressive accessibility by Ari Larissa Heinrich, who also translated another cult classic of queer Taiwanese literature: Qiu Miaojin’s Last Words from Montmartre (1996). Given the erratic style and structure of that book, Heinrich was perfectly suited to tackle the altogether zany world that Chi Ta-wei constructs in The Membranes.

Momo is Japanese for peach, the fruit depicted on the cover whose delicate and permeable skin recalls the membranes that encase us all. The character Momo is a dermal care technician who lives in T City in the final years of the 21st century. The world is unrecognisable, though Chi’s vision is powerfully prophetic: humanity has been forced to retreat to the bottom of the ocean because of the irrevocable effects of climate change.

Earth’s surface is no longer inhabitable, and the only records of human existence above water are stored on digitised “discbooks”. But this new reality has not daunted ever-enterprising human beings, who have found a way to build underwater domes in which exist cities and countries as we have always known them (and, yes, there are conflicts over which nations get how much of the ocean’s sizeable real estate).

China’s leading foreign actor on his first book and being ‘erased’ from films

Momo is aware of these details – of the history of humanity’s migration underwater – but her thoughts lie elsewhere. As the best aesthetician in the city, she wants to make sure her Canary Salon gives its clients the best care they can find. And with a secret skincare treatment that keeps them coming back, all seems to be well.

As the novel progresses, however, Momo is forced to deal with the loneliness she feels due to the absence of her mother, whom she hasn’t seen in 20 years. As a child, Momo underwent surgery to repair damage to her organs caused by the Logo virus, after which her body changed in ways she only partially recognises. A few years later, she enters boarding school and is left on her own.

Unexpectedly, her mother contacts her wishing to meet again, and Momo is sent into a flurry of uncertainty about whether the memory of her childhood – and indeed her current existence – is as it seems. She wonders about the shadows of knowledge she has about her body, her life and the world in which she lives.

It is at this point the novel introduces its jaggedly surprising plot twist and in so doing affirms its preoccupation with the messiness of identity, the insufficiency of gender categories, the constructed nature of reality, the perversity of human ingenuity and the frailty of our most cherished systems. It is almost unfathomable that, in 1995, Chi could have imagined a world so full of the terrors that technological rises inevitably bring, but he does and mostly to devastating effect.

Chi’s project is large, as is his vision, and the novel often bends under the force of such weighty contemplation. To be sure, as a work that might be called speculative or even science fiction, the novel lives in the space of frenetic hypotheticals; it imagines the future like the best of our dystopian meditations. But its allegories and symbols are sometimes heavy-handed, encumbering its artistry despite its wonderful provocations.