Review | The cognitive dissonance in adoring pets while eating meat and ignoring wildlife extinction explored in Henry Mance’s compelling review of how humans see animals

- Species extinctions may be the biggest existential threat to life on Earth, yet people who abhor animal suffering can disregard wildlife and farm animals’ fate

- The divide doesn’t make sense, writes Henry Mance in his exploration of the dissonant ways humans love – or don’t love – other creatures

How to Love Animals in a Human-Shaped World by Henry Mance, pub. Viking

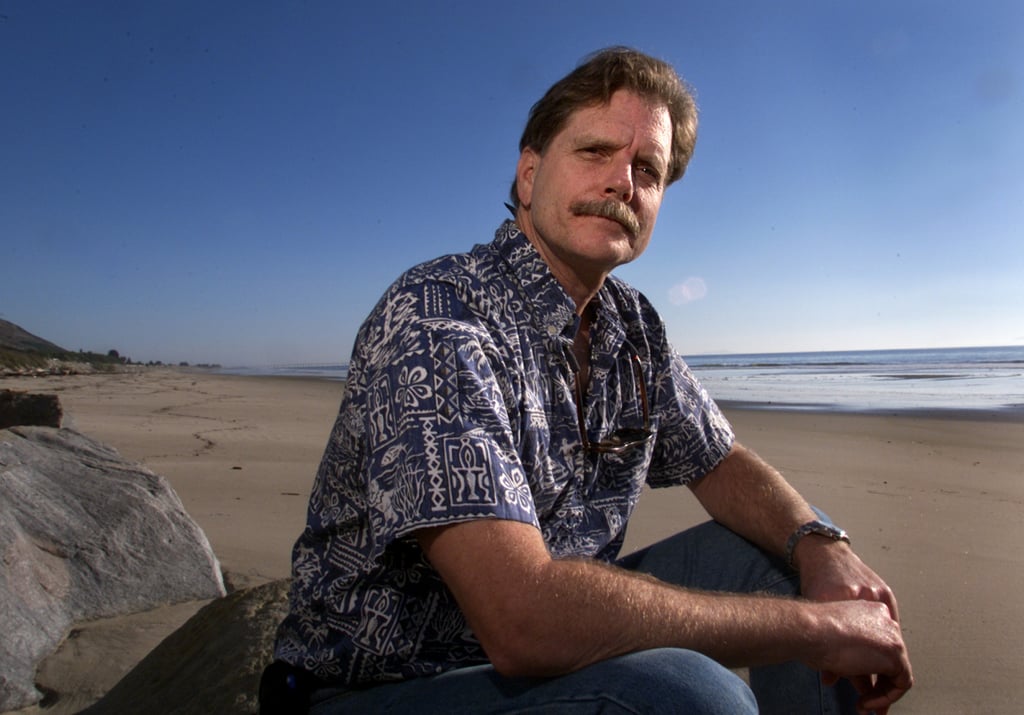

Rob Puddicombe’s alleged crime was trying to save rats. Two decades ago, the animal activist was arrested for scattering an antidote to rat poison across a small island park off the coast of California. He was hoping to spare thousands of rats, invaders to the island, from being poisoned. Park authorities wanted the rodents dead to save native animals, such as Xantus’ murrelets and Anacapa deer mice, from extinction. Puddicombe thought the rats deserved compassion, too.

His case became a cause célèbre: does loving animals mean an end to human-caused suffering for each living creature, great and small, or does it include killing some to save whole species?

The Puddicombe case – he was eventually acquitted for lack of evidence – isn’t mentioned in How to Love Animals in a Human-Shaped World, a sweeping and thought-provoking book by British journalist Henry Mance. But the central question looms large: what is the difference between people who love animals as individuals, each deserving an anguish-free life, and those who view animals as populations and species that need our protection to save the planet’s ecosystems?

Mance, the chief features writer for the Financial Times in London, doesn’t see one. He is both a vegan opponent of factory farming and an ardent proponent of biodiversity conservation. To him, “the divide doesn’t make sense”. To make his case, Mance takes readers on a ranging, first-person journey to a job at a British slaughterhouse, a Polish boar hunt, a blessing of the pets service at San Francisco’s Catholic cathedral and many other adventures.