Advertisement

Review | Tale of two Chinas – Taiwan and mainland, cosmopolitan and provincial – by Lo Yi-Chin, Faraway is a novelistic memoir about a father’s illness and a son’s dilemma

- Lo Yi-Chin’s memoir about the forces of illness, duty and bureaucracy sees its lead character torn between meeting the needs of a sick father and pregnant wife

- Faraway’s literariness references Italo Calvino, Gabriel García Márquez, Paul Theroux and V.S. Naipaul. But its terrain is that of two Chinas

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

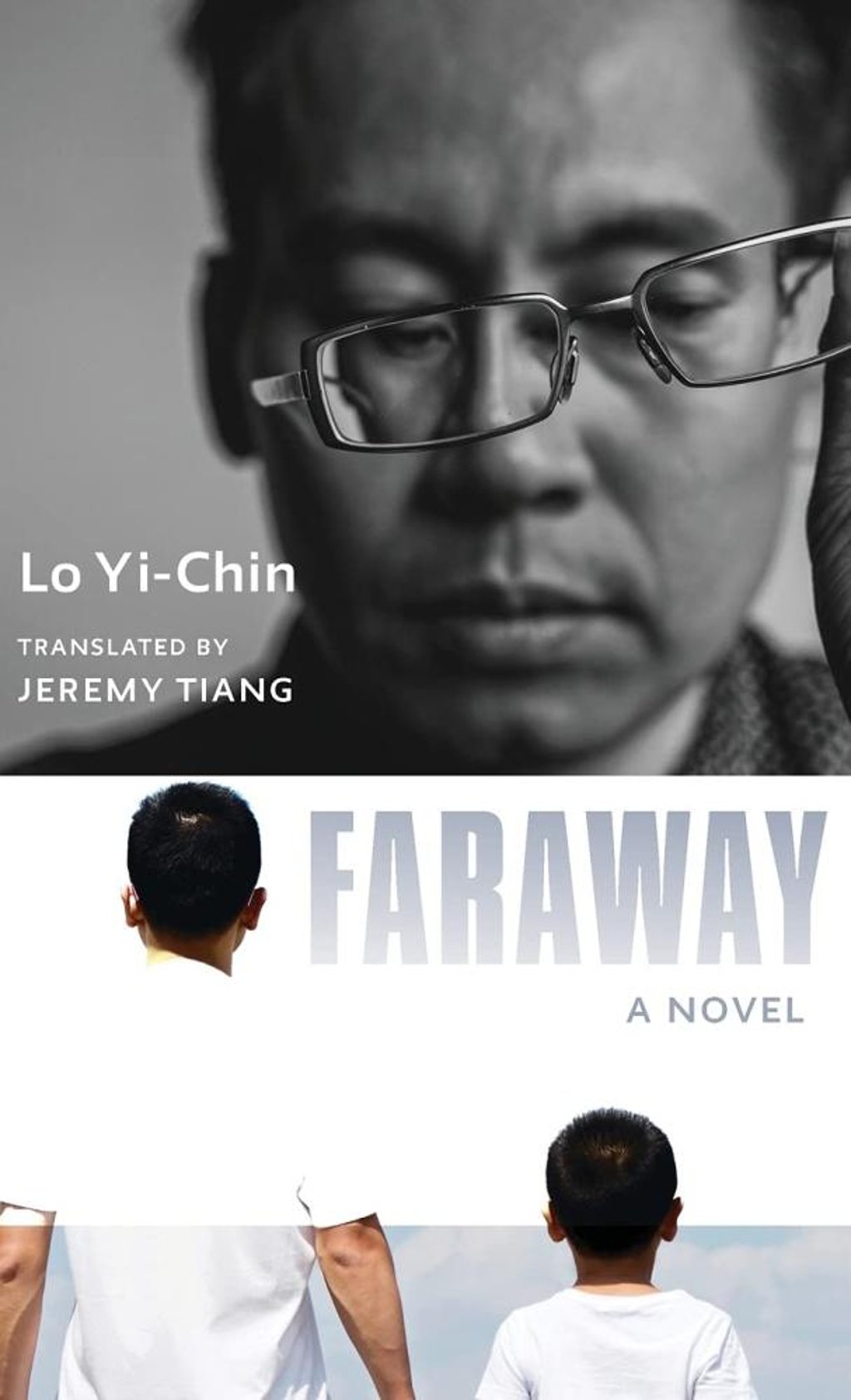

Faraway by Lo Yi-Chin (translated by Jeremy Tiang), pub. Columbia University Press

The latest work from Taiwanese author Lo Yi-Chin is a novelistic memoir, set between Taiwan and mainland China at the turn of this century.

Or perhaps it’s a novel where the main character shares the name of the author. According to its translator, “When I pressed him as to how much of the story was fictional, he claimed not to remember.”

Advertisement

Either way, Faraway is a work of deep introspection and sometimes overflowing imagery, a meditation on ageing and family, a memoir or novel of the wearing forces of illness, duty and bureaucracy.

It tells the painful story of Lo Yi-Chin’s journey to mainland China to bring back his aged and critically ill father.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x