Why painters can’t wear Crocs at work, and Jackson Pollock’s spotless shoes: author Charlie Porter on getting closer to artists by talking about how they dress

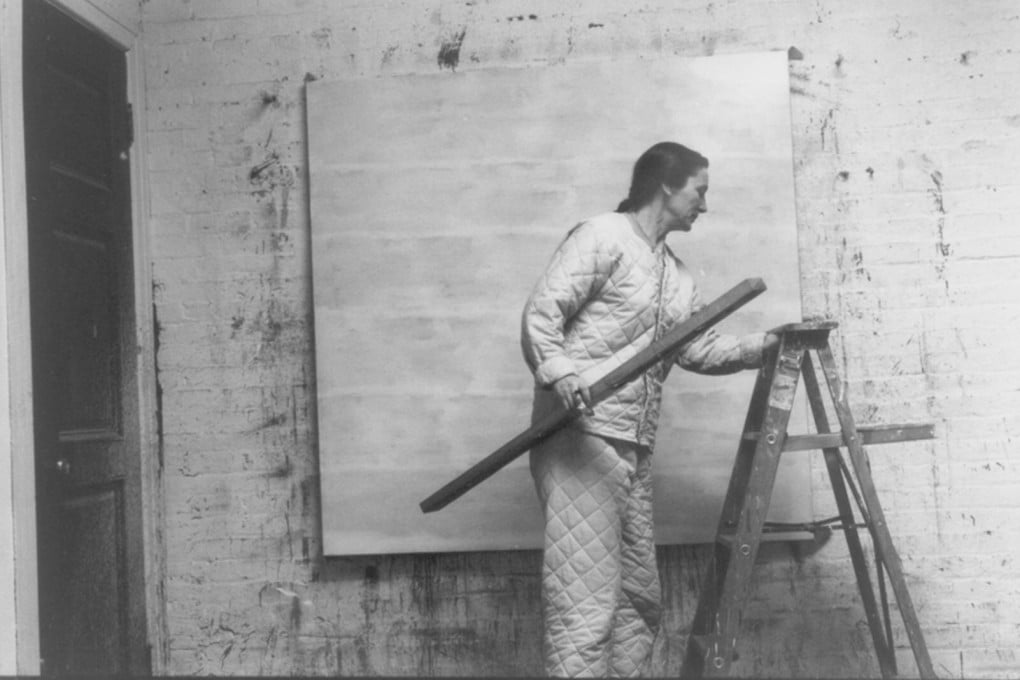

- A photograph of artist Agnes Martin in quilted jacket and trousers – ‘garments of supreme function and beauty’ – so intrigued a fashion writer he penned a book

- Charlie Porter has collected a mass of detail about what artists wore from head to toe, and says talking about their clothing ‘brings us closer’ to them

What Artists Wear by Charlie Porter, pub. Penguin Random House

In 2015, London’s Tate Modern held a retrospective of the American artist Agnes Martin, who had died in 2004. The catalogue included a 1960 photo by Alexander Liberman of Martin at work in her New York studio. She is perched on a ladder in quilted jacket and trousers.

“They are garments of supreme function and beauty,” Charlie Porter writes in his book, What Artists Wear. “The quilting makes a grid. Her hair is kept out of the way in a plait, which itself makes a grid. There is the grid of the bricks on the wall.”

Martin is known for her grid paintings. Porter, then a fashion journalist who also wrote about art, was so intrigued by the connection between her utilitarian clothing and what she was creating that he wrote a newspaper article about it. Then he began to explore the concept more widely. He found that many artists, who disliked analysing their work, revealed more about it – and themselves – when they talked about what they wore. His book is the enthusiastic result.

Porter dates the year a garment became art to 1913, when the French artist Sonia Delaunay made – and wore – the Simultaneous Dress. (The French poet Guillaume Apollinaire described it as “a living painting”.) With more than a century of subsequent activity to choose from, he leaps between artists with unflagging delight. Occasionally, the reader has to take a break from the Ohmygods and breathless passion; at one point Porter himself writes, solicitously, “Let’s get some air …”