Then & Now | Who writes Hong Kong memoirs? Examples from World War II survivors to policemen to those who just want to settle scores can reveal history in a new light

- Police memoirs have begun to appear in quantity from Hong Kong which, until recently, were among the most elusive

- Some recent offerings were clearly written in response to earlier works by former superiors or contemporaries; a desire to ‘set the record straight’ is apparent

Looking back is a corollary of advancing age. Life’s arc tends to make more sense as the trajectory reaches certain vantage points, and distance – whether from places, people or events – lends valuable perspective.

Retirement, sometimes far away from a life once lived, spent among those who stayed at home who – all too often – have little interest in someone else’s very different life lived on the other side of the world, brings formerly exotic, everyday experiences into sharp contrast.

Individuals mostly remember what they “choose” to remember. Without detailed diaries or other aids to accurate chronological recall, human memory gradually sifts recollections and reorders events, usually not from a deliberate desire to rewrite the past, but to make sense of it, in terms of a coherent story.

Personal motivations for memoir writing are various; a desire to be better understood by later generations of one’s own family often plays a key role. Dedications to children and grandchildren, as well as a spouse who shared long-ago, far-off adventures, are commonplace.

Whether a personal story is released close to the events it chronicles, or some decades later, often affects how accurate and decisive a memoir is. A degree of individual score-settling characterises some later publications; with potentially controversial people safely dead – and the risk of libel suits thus eliminated – more honest accounts become possible.

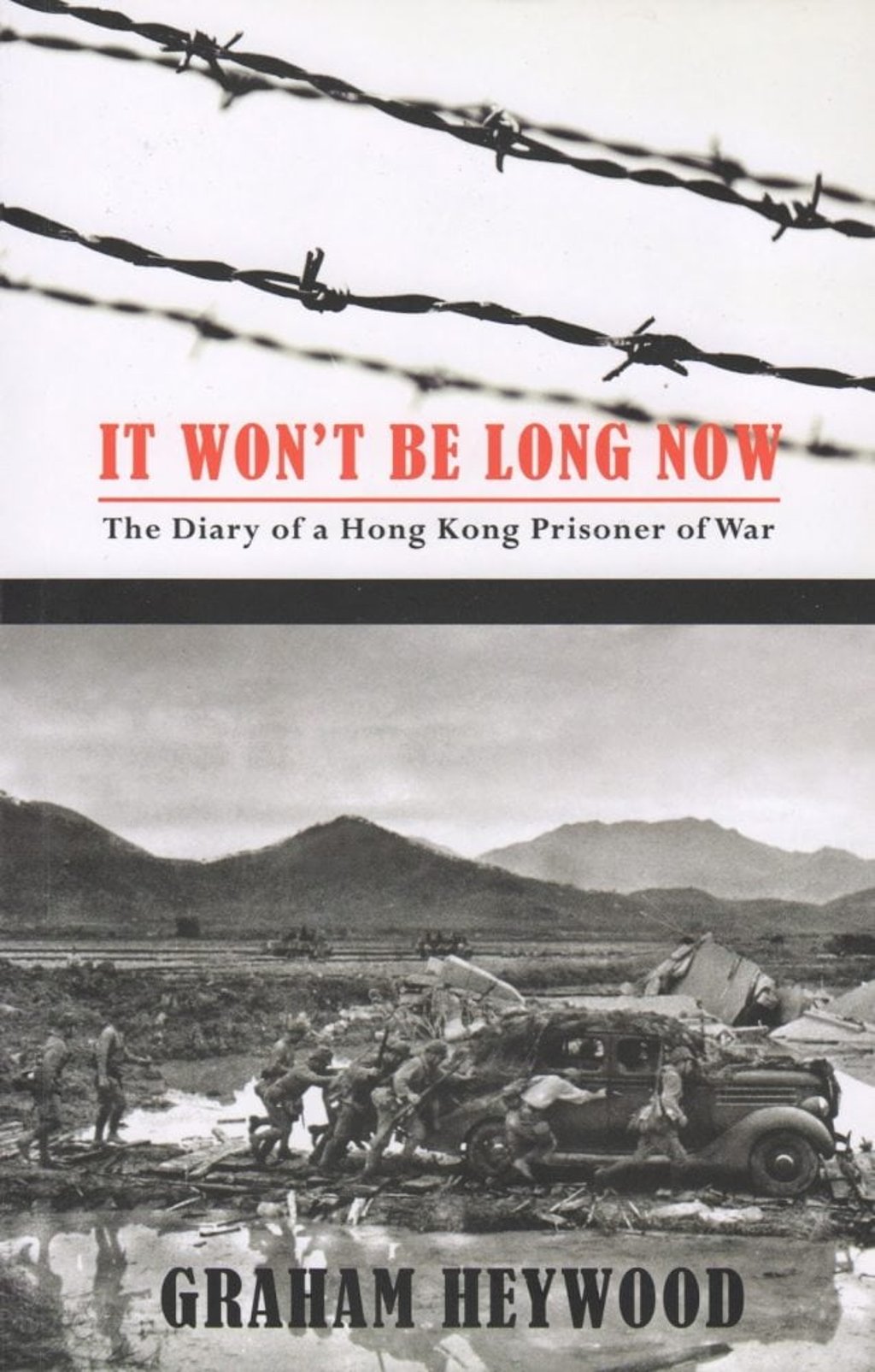

Distinct genres exist within Hong Kong memoir writing. Accounts of prisoners-of-war and of civilian internee camps enjoyed a brief flowering after World War II ended. As immediate interest tapered off, and people went on with their renewed peacetime lives, publications dwindled. Intermittent releases continued, until public interest resurged from the 1970s to the 1990s when significant historical anniversaries chimed.