Review | The Sassoon dynasty and its succession problem: how bad decisions and infatuation with the English aristocracy destroyed its business empire, told by a Sassoon

- The Sassoon dynasty built the greatest family business empire of modern times with astonishing speed, and just as quickly successors frittered its fortune away

- Joseph Sassoon charts its rise, which saw the first woman run a global business, and its fall, which he blames on poor choices and the family’s anglicisation

The Global Merchants: The Enterprise and Extravagance of the Sassoon Dynasty, by Joseph Sassoon, pub. Allen Lane

At its height, in the early 20th century, the Sassoon dynasty far exceeded just about any other family business in history. Stretching from roots in Baghdad, spanning the Indian subcontinent, becoming a force in the coastal cities of China and the smart drawing rooms of Mayfair, the dynasty had wealth and staying power … until it didn’t.

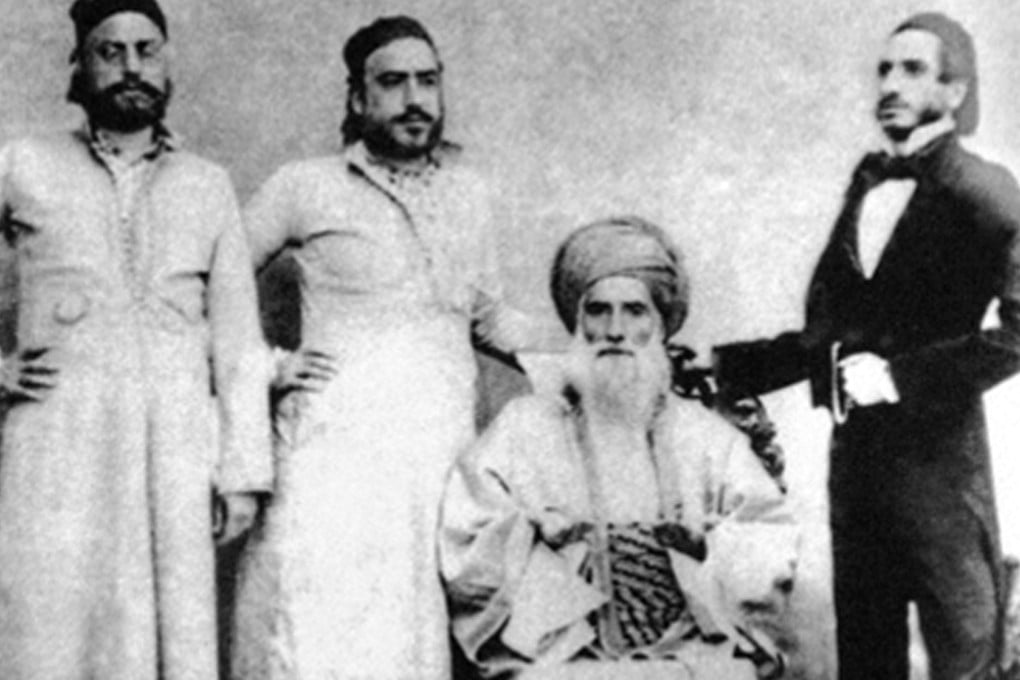

There is a shelf of books on the Sassoons, but this is the first comprehensive history by one of its own. Joseph Sassoon, an American academic specialising in Iraq, hails from a branch of the family descended from Sheikh Sassoon (1750-1830) that divided from the main bough in the 19th century.

Fortunately, given the wealth of archives consulted for this book, Sassoon is fluent in Arabic, Hebrew and the Baghdadi-Jewish dialect, the arcane patois of much of the family’s internal business correspondence.