‘The big lie of the Marcoses …’ For Filipino novelist Miguel Syjuco, reality is uncomfortably close to his satire about a Philippines presidential election

- Novelist’s second book, I Was the President’s Mistress!! sends up a scandal-plagued government and a succession of corrupt Philippines statesmen in bawdy style

- His satire is not without hope but he fears it comes too late to dissuade Filipinos from voting into power ‘inept’, ‘big-mouth liar’ Ferdinand Marcos Jnr

I Was the President’s Mistress!! by Miguel Syjuco, pub. Farrar, Straus and Giroux

“We’ve had the erosion of democratic checks and balances, of freedom of the press … deported foreigners critical of [the] administration, jailed opposition candidates. All of that.”

“The Duterte campaign slogan was ‘change is coming’. Well, yes: people are less free, much more violent, we’re a poor country with a weaker economy and are consistently ranked last in the Covid resilience ratings. We’re a shambles; that’s the change that has come.”

The Philippines is the setting for Syjuco’s second novel, I Was the President’s Mistress!! Coming 14 years after its first draft and Syjuco’s Man Asian Literary Prize-winning debut, Ilustrado (honoured at a ritzy shindig at Hong Kong’s Peninsula hotel), on its most accessible level it is a bawdy gambol through the salacious recollections of Vita Nova – “singer, dancer, movie star, philanthropist, former paramour to the most powerful man in the realm”.

Fundamentally, however, it is a caustic exposé of the state of the nation as also revealed by Vita’s friends and enemies, including the president, a bishop, a DJ, a journalist, an ex-sailor, an opposition politician and a failed assassin.

Marcos’ message is essentially ‘make the Philippines great again’, but he’s so feckless and inept that he doesn’t show up for debates

A professor of literature at New York University Abu Dhabi, from where he is speaking, Syjuco, 45, has no regrets about not following his parents into politics, even as he contemplates the increasingly bleak future into which he fears the Philippines is plunging.

“Marcos’ message is essentially ‘make the Philippines great again’,” he says, “but he’s so feckless and inept that he doesn’t show up for debates, he doesn’t stand before real journalists.

“He’ll get interviews with sympathetic or lifestyle journalists, with their softball questions, and when it comes to real scrutiny he’s absent – all the other candidates show up.

“He has been dismayingly popular in the polls – and not all of them can be cooked. We’re a country that praises celebrity and increasingly infamy, that’s the sad thing.

“The lie is that the allegations – the convictions, actually – all the embezzlement, all the sins of the Marcoses, are being cast by the Marcoses as lies. They are using their lies to try to cast the truth as a lie.”

I Was the President’s Mistress!! turns up the heat, Syjuco unleashing it to sizzle with lurid sex, Rabelaisian jokes and bacchanalia; douse in vitriol a scandal-lashed government; tear down racists and misogynists; serve as an ironic equal-opportunity goader of assorted belief systems; and scathingly lampoon history’s parade of corrupt Filipino statesmen responsible for “bulldozing limits to presidential authority”, as one character puts it.

All this is wrapped in a blizzard of pop culture and occasional sporting references – Billy Joel, the Green Bay Packers, Edward Hopper, Metallica, AC/DC, John Mellencamp, Fenway Park, Bonnie Tyler, Frank Zappa – that itself comes, at times, in a torrent of “modern-day” language (and titular punctuation) shaped by social media.

It is a work, says Syjuco, coloured by “the way we speak now” and one illuminated by ready-made aphorisms (“corruption thrives when temptation meets tolerance”; “the world can’t stand a free woman”; “politics is showbiz for ugly people”; “chaos offers everyone opportunity”). Even allowing for a century of literary evolution, comparisons with Ulysses are inevitable.

If there is any hope for “new life” for the fictional Philippines, it is embodied by the 30-something Vita Nova herself: despite being another flawed character, Syjuco says she “comes in with community support, good ideas and a heart in the right place – which should be enough for anyone in a democracy to have access to power”.

He does, however, caution against putting real faces to the names of his creations: “they are everybody and nobody, my characters are based on archetypes, not people”, he says.

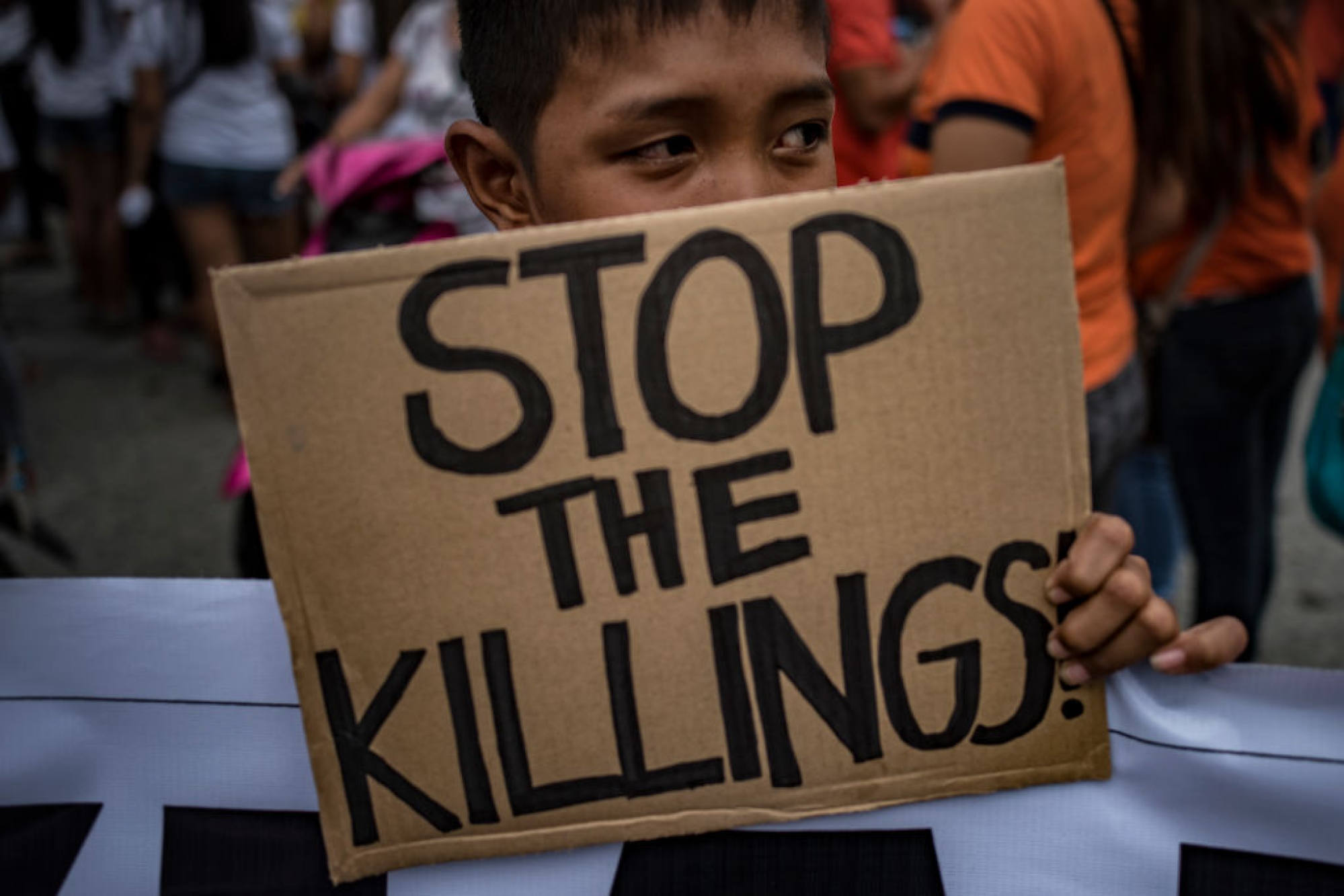

Not that he can be accused of being merely a distant observer of events in his homeland, about which he writes for The New York Times. “I go in under the radar,” he reveals, which allows him to report from crime scenes and within communities where there is “fear and dismay”.

And although he realises the book will appear too late (“we novelists work at a glacial pace”) to affect this year’s vote, Syjuco says, “If I can change just one person’s mind, that’s what it’s about, engaging readers one at a time.

“People will see what’s in the book, what’s happening in the elections, in the campaigns, on the streets. Things will resonate and maybe have some influence in the long term. The book is about our relationship with truth. Whom and what do we believe?”

And because it encapsulates a zeitgeist reaching far beyond the Philippines, it is also a novel “designed to play with offensiveness, to examine and maybe push the boundaries of free speech”.

“Why do we have to be afraid of offending people?” asks Syjuco. “Why do we have to make everybody happy?”