Review | Novel gives voice to the girls Mao Zedong had sex with, in the powerful form of a confessional

- Vanessa Hua’s Forbidden City tells its story in the form of a confessional by the fictional Mei Xiang, pulled at 15 from a dance at China’s Zhonghanhai compound

- ‘Fiction flourishes where the official record ends,’ Hua writes, and, with sections that convey a powerful verisimilitude, her book mostly bears this out

Forbidden City by Vanessa Hua, Ballantine Books

“Like boxes within boxes, and puzzles within puzzles”: this is how one American writer described the layout of old Beijing. At the heart of the city’s nested squares sat the Forbidden City, where the emperor ruled and resided, his ceremonial halls set along the “dragon’s vein” that runs north to south through the centre of the city.

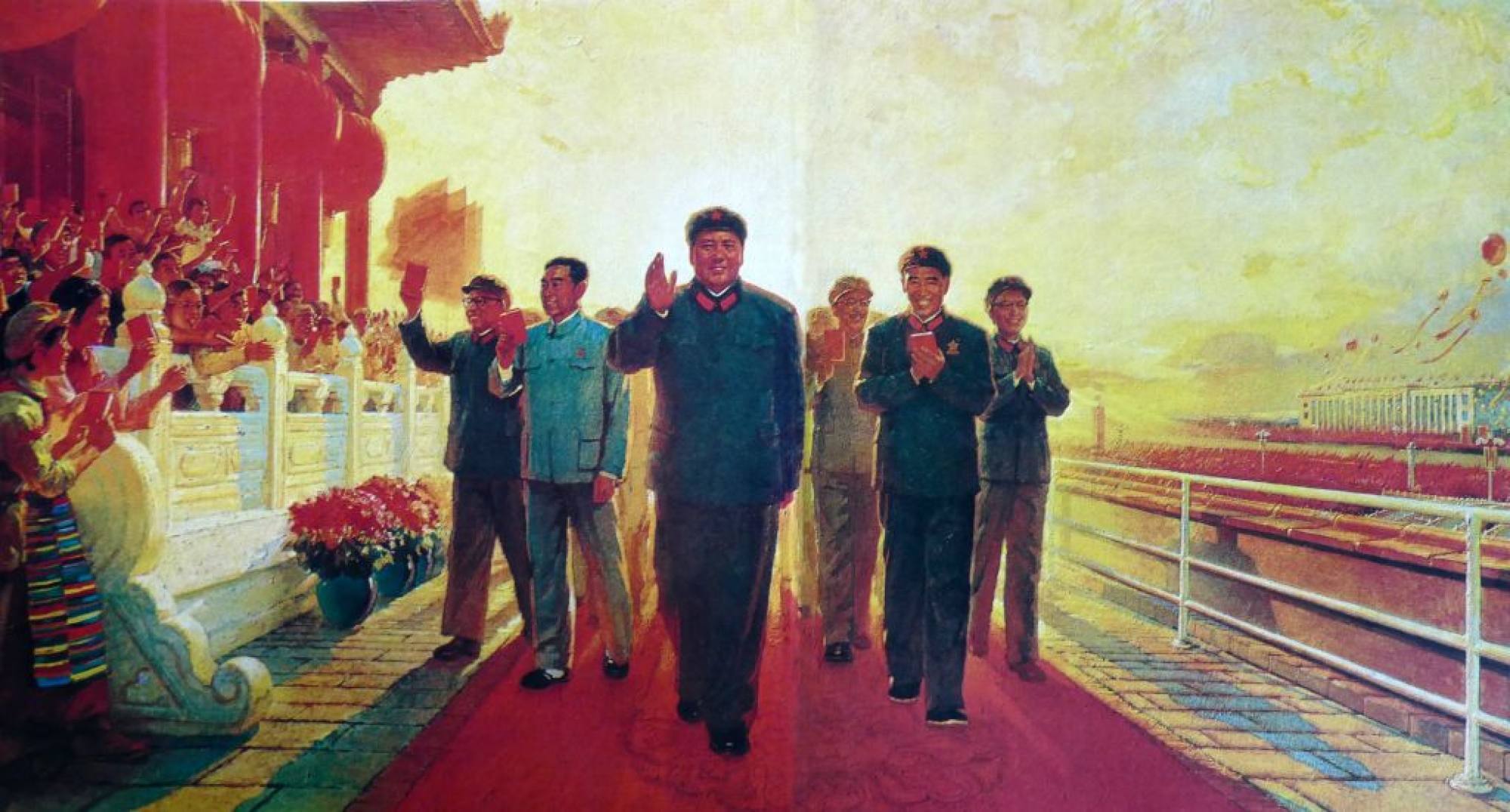

In 1949, the new leader, Mao Zedong, took up residence at Zhongnanhai. He had been sceptical of establishing himself and his government in the heart of imperial Beijing, but after a short stay in the Western Hills he was persuaded to move into a courtyard compound there. In 1966, he relocated to lodgings attached to the compound’s indoor swimming pool.

Zhongnanhai became the black box of Chinese politics; behind its high vermilion walls, the highest echelons of the party lived and worked beyond the sight and scrutiny of the people.

Accounts of life in Zhongnanhai are few. In 1994, the memoirs of Mao’s personal physician, Li Zhisui, were published, offering a detailed – though not uncontested – account of the politics and personalities at the top of the party. The book’s most lurid sections include descriptions of Mao’s sexual proclivities: in particular, his predilection for selecting young women at leadership dances in the compound, and leading them away to a specially prepared room containing a double bed.

Li’s memoir tells of Mao spreading venereal disease among members of the dance troupe who provided partners for the cadres, resisting the doctor’s urging to cease his activity, or even to observe basic hygiene: “I wash myself inside the bodies of my women,” he apparently told Li.

In Vanessa Hua’s novel Forbidden City, the author attempts to give voice to those voiceless and exploited girls who were ferried into Zhongnanhai for Mao’s pleasure, offering a confessional narrative told by Mei Xiang who, at the beginning of her story, is not quite 16.

Mei’s narrative, told in retrospect from 1976 San Francisco, feels most powerful when it is personal: her worries about the family she has left behind in the village; her profound sense of insecurity as to her position in the troupe and, later, her relationship with the Chairman; the increasing strain of claustrophobia – such sections strike the reader with a powerful sense of verisimilitude and insight.

The sex scenes describing the encounters between the 72-year-old Chairman and the teenage Mei are startlingly frank; Hua resists the urge to euphemise or redact these encounters, and there is a nauseating force to their reality.

The challenge of first person is always in exposition, though; and Hua’s novel necessarily incorporates explanatory sections to introduce the swirling and complex politics of the era.

Done either as dialogue or internal monologue, these passages impose on the narrative, pulling the reader out of the compelling emotional world of Mei’s individual experience.

Hua writes in her Author’s Note that “fiction flourishes where the official record ends”; it is an assertion that Forbidden City mostly bears out, despite some of the challenges of melding the personal and political, compelling the reader to contemplate the emotional reality of experiences that demonstrate how absolutely power corrupts.