Advertisement

Hong Kong in the late 1990s the star of ‘A Catalog of Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On’ – think Hello Kitty, PalmPilots and everything Japanese

- Hong Kong author Dung Kai-cheung paints a picture of Hong Kong just after the handover from Britain to China in 99 ‘sketches’ translated into English

- A Catalog of Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On is a remembrance of things past and the city’s youthful obsession with all things Japanese, like Hello Kitty

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

1

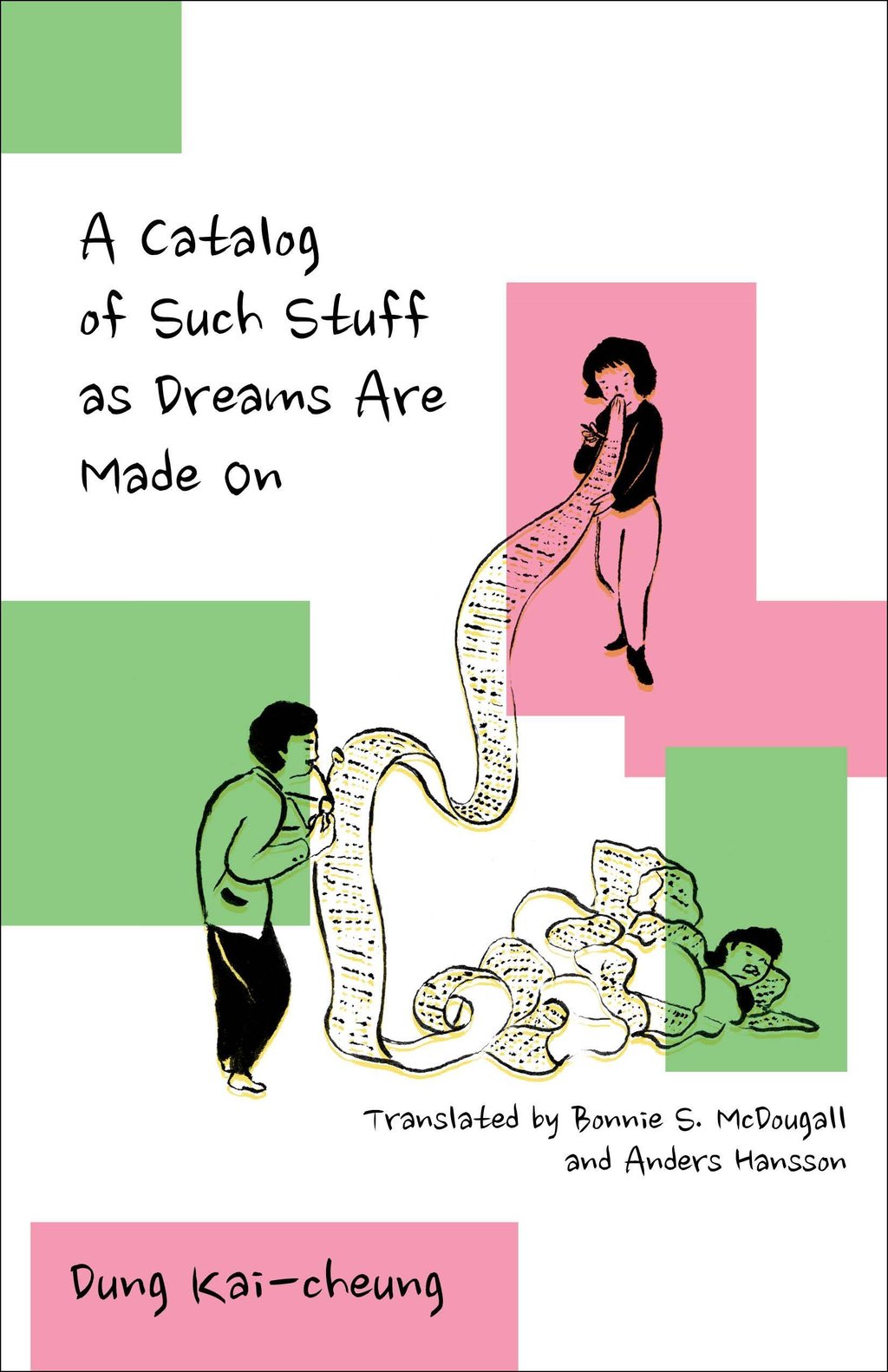

A Catalog of Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On, by Dung Kai-cheung. Published by Columbia University Press

Dung Kai-cheung may be one of Hong Kong’s most original, lauded and prolific authors but for English-language readers the pickings have been slim.

Atlas: The Archaeology of an Imaginary City, which he wrote in 1997, was the first of his books to be translated into English. That was in 2012. The translators were Bonnie McDougall and Anders Hansson.

Advertisement

In 2017, a slender volume called Cantonese Love Stories appeared; this was their translation of 25 of the 99 tales in The Catalog, which had been published in Chinese in 1999.

Now, all 99 “sketches”, as Dung prefers to call them, have been published as A Catalog of Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On. Again, the translation is by McDougall and Hansson but the English title, taken from a line in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, was chosen at the last minute by Dung.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x