Review | Decolonising culture: Paul Gauguin’s Javanese ‘mistress’ Annah and ‘Malay girl’ in a W. Somerset Maugham short story given voices in novellas of Mirandi Riwoe

- Australia-based writer Mirandi Riwoe retells the story of Annah the Javanese, raped as a child and traded to Paul Gauguin, who painted her naked on a chair

- She gives a name and a voice to the ‘Malay girl’ servant of W Somerset Maugham’s The Four Dutchmen, and a clear-eyed, furious consciousness too

The Burnished Sun by Mirandi Riwoe, pub. University of Queensland Press

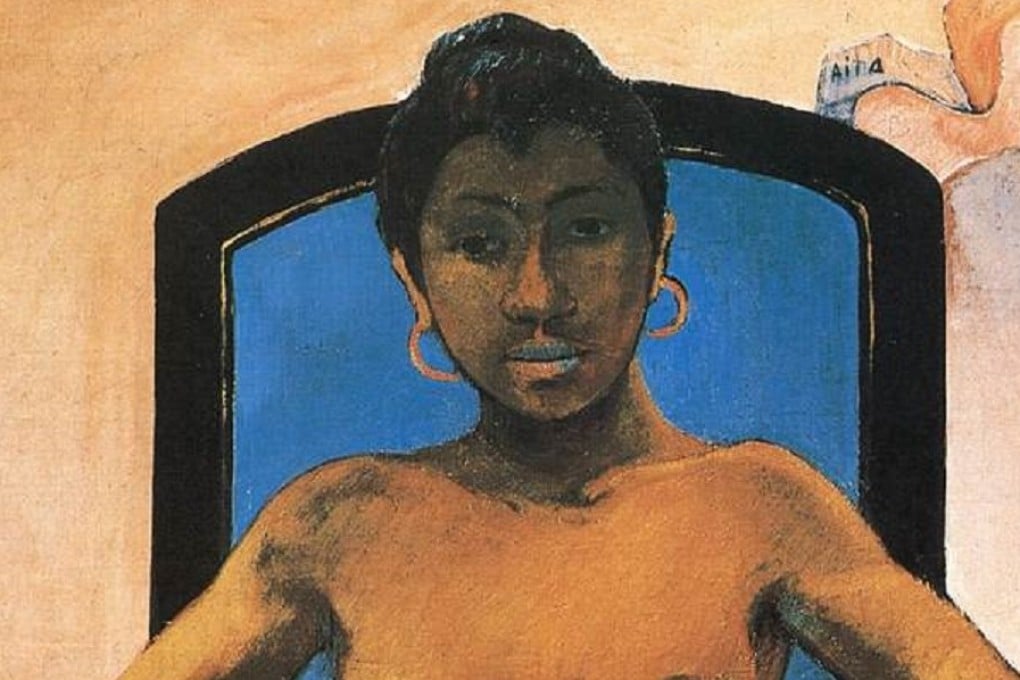

Paul Gauguin depicts Annah the Javanese perched awkwardly at the front of a blue upholstered chair, naked, meeting the painter’s gaze, in an 1893 canvas.

She is described in various sources as his “lover”, and the common version is exemplified in this one from the Art Institute of Chicago’s 1959 book, Gauguin: Paintings, Drawings, Prints Sculpture: “While visiting Brittany with his mistress, Annah the Javanese, Gauguin became embroiled with sailors who had molested Annah. He suffered a fractured ankle and was laid up for weeks. (Annah, incidentally, repaid his gallantry by ransacking his studio in Paris and vanishing forever.)”

Brisbane-based author Mirandi Riwoe’s novella Annah the Javanese, selected for the prestigious Griffith Review Novella Project in 2019, and the opening story in her collection The Burnished Sun, present the same sequence of events. Here, though, the polarities are reversed, nothing is distorted through the thick fog of Gauguin’s artistic genius; instead, it is sharpened through the eyes of Annah, a child raped and traded by powerful men.

Riwoe’s Annah is intelligent and analytical, and through her eyes we see Pol (as she calls Gauguin) as a multifaceted character – artistry and arrogance, sympathy and fixedness of mind – and never as the protagonist.