Inside the surveillance state: how China coerces its people by making them think their every move is being watched

- The tools of modern surveillance, created and perfected in Silicon Valley by Facebook, Google and Amazon but married to a state power, have a powerful impact

- China’s spy cameras and data collection may not be all-seeing, but people only need to think they are for them to work, say the authors of Surveillance State

“State surveillance has been with us as long as there have been states,” point out Josh Chin and Liza Lin in their new and thoroughly researched guide to the Chinese Communist Party’s attempts to mould society through observation and mass-data collection.

In a way, they tell us in Surveillance State, there’s nothing new here.

“As far back as 3800BC, Babylonian kings in what is now Iraq pioneered an embryonic form of mass-data collection, using cuneiform and clay tablets to keep a constantly updated record of people and livestock.”

“China didn’t invent any of this,” says Chin, with Wall Street Journal colleague Lin on a video call from Singapore. “Almost all these technologies were invented in Silicon Valley by Google and Facebook and Amazon, perfected by them, and arguably used more effectively in terms of collecting data and using them to analyse and predict human behaviour.”

But whereas these tools were originally intended for what is now known as surveillance capitalism – compiling digital dossiers on consumers to better sell their attention to advertisers – the Communist Party’s application is more sinister. Or more public-spirited, it might claim.

“The difference is what happens when you marry those technologies to a state power,” Chin points out.

My family’s Hainan holiday nightmare shows misery of travel in zero-Covid China

China’s monitoring is on a scale big enough to be seen from space. By early 2020 there were already 350 million cameras installed in China’s public areas, while 840 million smartphones provided a constant stream of location data.

Moreover, China’s tech companies have been willing accomplices in providing access to their own vast stores of information on consumer behaviour, often linked to real-time observation of subjects.

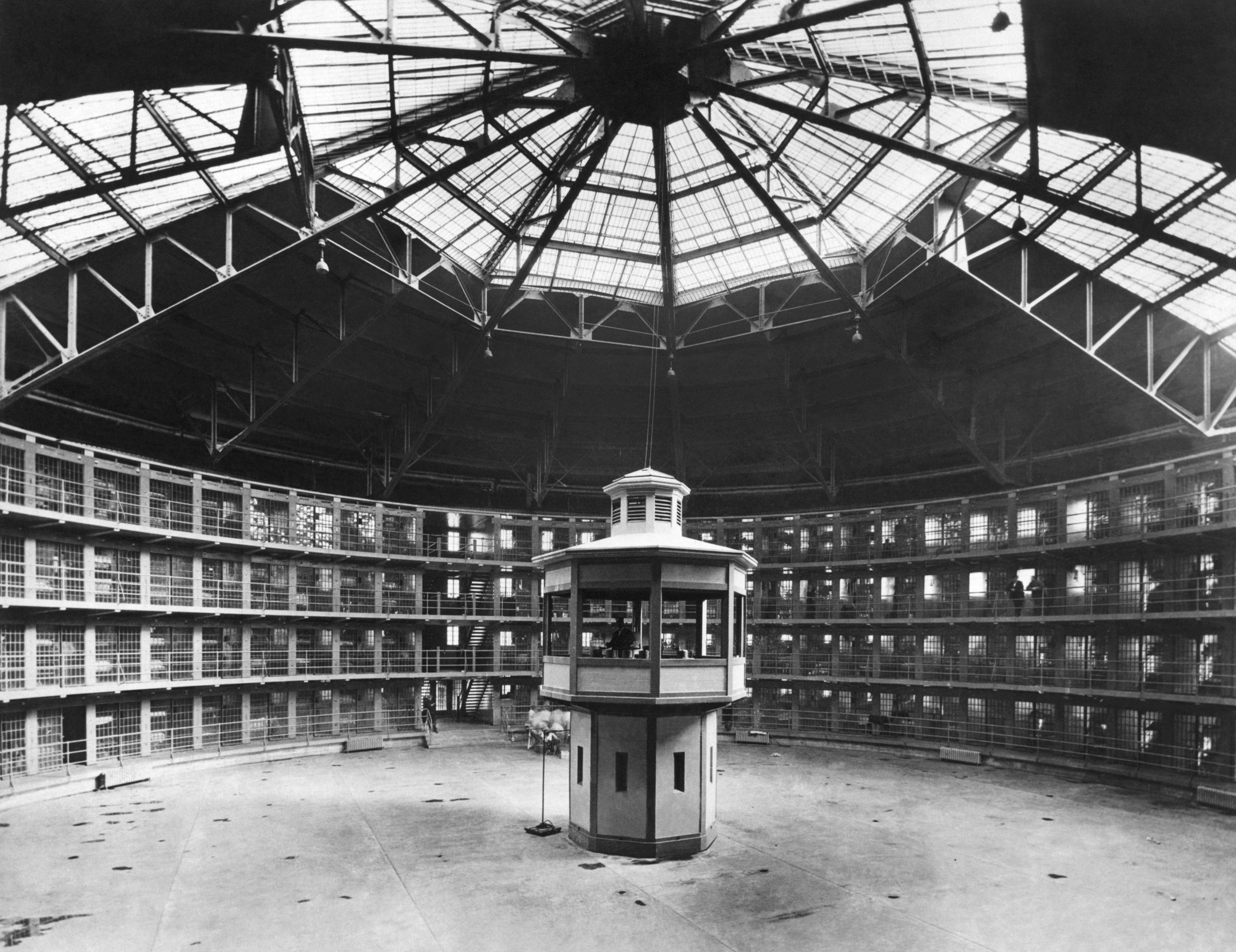

The underlying idea seems to be that of philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, a prison design that allowed for continuous observation of inmates in cells down multiple arms viewed from a central point.

In fact it was impossible for all the prisoners to be observed continuously, but the fear of being watched was supposedly sufficient to quell bad behaviour, and the Communist Party is apparently attempting to apply this effect to the entire country.

Be flagged as suspicious in China or buy a catapult online just for target practice, and soon afterwards there may be a knock at the door, as one of the authors’ interviewees discovered.

“They thought I was going to use it to shoot out their cameras,” he told them.

You can’t really run a modern state without collecting a lot of data and information about the people who live in it. That’s just as true of the UK or the US as it is of China or Russia.

“Facebook can do a lot of things with your data,” says Chin, “and maybe do more with data than the Chinese government can. But you do have a very clear choice whether or not to use Facebook, and now in Europe you can go to Facebook and demand that they delete all of your data. In China you don’t have those choices.”

And Facebook cannot arrest you. Google cannot put you in jail. Amazon cannot execute you.

But Chin and Lin are no hawkish think-tank desk warriors who may be dismissed as “China-bashers”. They’ve reported for The Wall Street Journal everywhere from the bustling boulevards of China’s coastal cities to the more remote corners of Xinjiang, thousands of kilometres away.

A theme of the book is the contrast between how surveillance is proudly promoted to the Han majority in the east of the country as the means to make lives safer and more comfortable, and its application in the west to control the often restive minority populations by identifying for detention individuals the algorithms pick out as possible future threats. But the authors acknowledge the benefits of mass surveillance, and the willingness of many ordinary Chinese to embrace it.

“You can’t really run a modern state without collecting a lot of data and information about the people who live in it,” says Chin. “That’s just as true of the UK or the US as it is of China or Russia.”

Surveillance is not necessarily authoritarian in itself, but systems that use AI and algorithms are opaque, often even to those employing them. And when these systems are used predictively, there’s no way to interrogate the conclusions they come to, although there’s evidence of error from around the world.

Police have been known to tweak surveillance systems to nudge them to support conclusions already reached.

“Xi Jinping thinks that he has a system that is not only more responsive but can tell the future if you give it enough data and if you have the right algorithms,” says Chin.

Some police officers were delighted to give the authors a tour of their operations, busy identifying those seen parking illegally or fly-tipping, and smoothing traffic flows by predicting congestion. More significant was the identification and rescue of kidnapped children who had passed in front of the omnipresent cameras. But some claims were overblown.

“There have been several studies in the past that show that cameras will reduce crime – petty crime and smaller crimes,” says Lin. “But it’s nothing to do with the cameras themselves. It’s the idea that the cameras are watching. The crime goes down in that neighbourhood but you see more crime in surrounding neighbourhoods that don’t have cameras. So you’re essentially pushing the crime from one neighbourhood into another.”

There’s also evidence that the technology isn’t entirely up to the job, that various systems are not as coordinated as claimed, that they are being ineptly operated, or have been installed as vanity projects, perhaps principally to send the right messages back to Beijing or for the fat kickbacks such multimillion yuan purchases can produce.

“I think we shouldn’t be so arrogant as to say that China is doing all this in order to wreck the democratic social order,” says Lin. “The bottom line is that it is doing all this for its own purposes and to justify itself to its own citizens more than anything.”

“It’s totally possible this whole thing is going to fail,” says Chin. “But they have implanted in the minds of Chinese people that they’re being watched all the time. And that certainly is paying dividends.”

To read Surveillance State is to watch the watchers.

Surveillance State: Inside China’s Quest to Launch a New Era of Social Control by Josh Chin and Liza Lin, pub. St Martin’s Press