Review | Italian-American story of migration suffers from too many plot strands that get in the way of the main narrative

- Maria commits a transgression in Italy that forces her and her mother to emigrate. In due course she gains a job in Hollywood and a boyfriend, but then comes war

- If Anthony Marra had kept his novel Mercury Pictures Presents focused on her story instead of pursuing multiple other narratives, it would be more satisfying

“It was a long time since he felt at home anywhere,” the narrator in Anthony Marra’s Mercury Pictures Presents tells us about a character we meet only in passing but who embodies the sense of displacement almost every character in this novel feels.

Most often, that sense of homelessness is the result of being uprooted geographically. At other times, it is born from relationships and situations that wander too far from the safety of certainty. The characters try to make the most of circumstances entirely out of their control, tenaciously reinventing themselves as often as they need to.

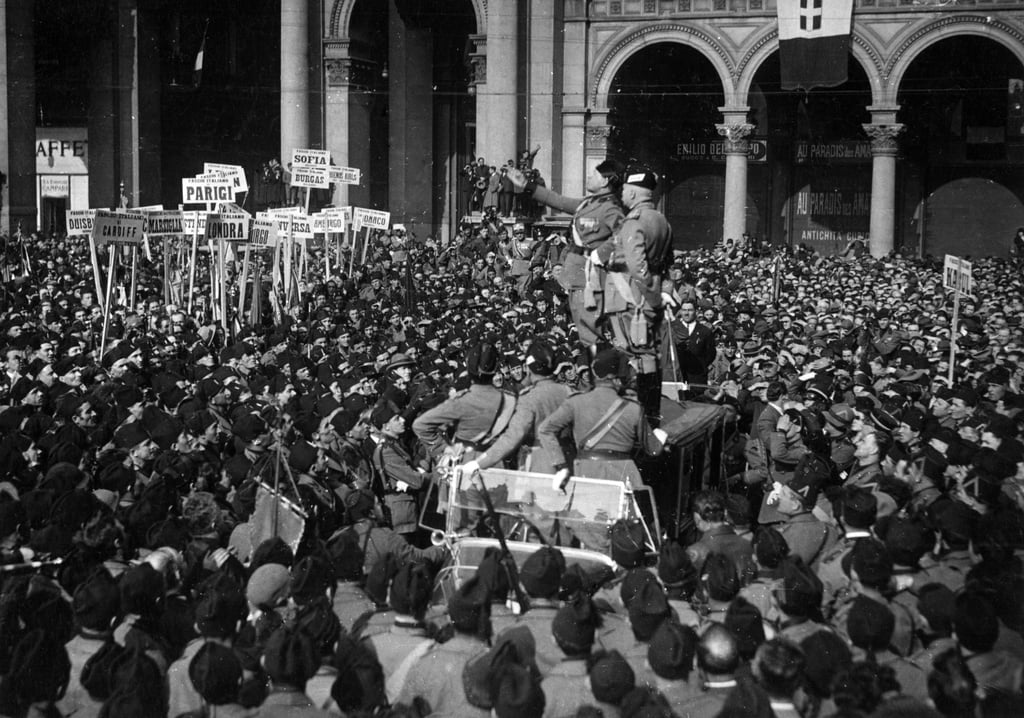

Though the sprawling novel contains multiple narratives, its focus is on Maria, whose childhood transgression in Mussolini’s Italy changes the trajectory of her family’s life.

Precociousness causes her to make an irrevocable mistake that reveals to the government her father, Giuseppe Lagana’s, anti-fascist advocacy. For this he is sentenced to confino, or internal exile.

As a result she and her mother, Annunziata, emigrate from Rome to Los Angeles to live with her three great-aunts and to make a life for themselves no longer possible in Italy.