Then & Now | How Hong Kong tailors made the colour coordinated ‘Matchee-Matchee’ look the city’s signature style

- From the 1920s to the 70s, Hong Kong’s gold standard for women was “Matchee-Matchee” – an attempt towards stylistic, fabric or colour coordination

- The name comes from the pidgin English term deployed by dressmakers, ladies’ tailors, cobblers and other sartorial artisans

Was there ever a distinct Hong Kong fashion “look”, that translated across the ethnic and national groups that made their homes here from the colony’s mid-19th century beginnings, and on to the present day? One commonality existed; from the 1920s to the 70s, Hong Kong’s gold standard for women was “Matchee-Matchee” – the pidgin English term deployed by dressmakers, ladies’ tailors, cobblers and other sartorial artisans to signify a valiant attempt towards stylistic, fabric or colour coordination. To a remarkable degree, this distinctive fashion statement retains contemporary local echoes, in certain circles.

To enable this look among the cognoscenti, an ever-enterprising, perennially smiling little chap, tucked away down an otherwise unpromising Kowloon backstreet and up a few flights of dingy stairs, and too shrewd by half for his customers’ good, would gleefully chirrup “Hello Missee! Matchee-Matchee …” the moment Madame walked through the door. Bundled up in Madame’s woven-rattan Hong Kong basket, she concealed a few more frock lengths, ready for the next thrilling instalment in her blissfully unaware, ongoing sartorial saga.

Many was the Hong Kong maven who hit her personal stride in her 20s, and stayed fiercely loyal to her chosen style and colour combinations, with only minor variations on the general theme, until – inevitably – death did them part. And after all, why not? Understated elegance is not a Hong Kong hallmark; never was – and never will be.

Artisanal labour standards in China – as elsewhere in pre-industrial Asia – seldom reflected actual prices charged; high quality workmanship was simply expected. And in the days before machine-driven mass production dramatically lowered costs, a pair of shoes – handmade or otherwise – was just a pair of shoes. More affluent shoppers – much like today – ordered as many outfits as they wanted. And if “Missee” wanted everything she wore to “Matchee-Matchee” – then so much the better.

And whatever her heart desired – and the old man’s purse could accommodate – was readily available. If the fright-inducing combination of Lime Cordial, Olde Rose and Bottle Auburn had somehow become an individual’s preferred and perennial palette, then – almost quicker than he could say “mo man tai” – something in that order of magnitude could be magicked up by her preferred tailor. A snippet of verse from the late 30s amusingly sums up the type:

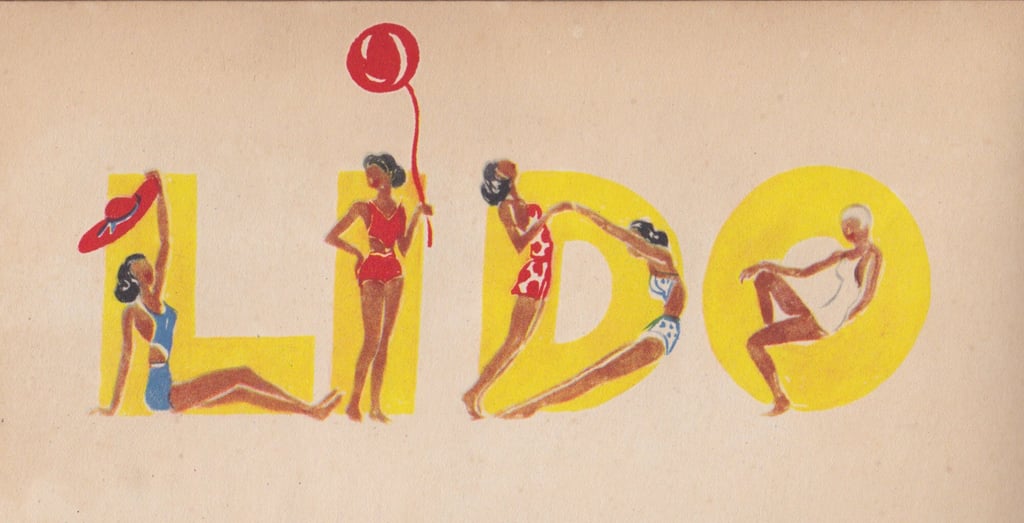

She ordered gowns

made by the score

Of styles defying speech –

For swimming,

Madame’s bathing suits

Caused riots on the beach!

“Matchee-Matchee” shoes, in particular, were handmade in the exact colour of a frock or other outfit, and on occasion from the same material – satin was a favourite. Sometimes leather could be dyed to the same shade; this was more serviceable than a fabric upper, which would become scuffed and sweat-stained after a few parties, or being trodden upon by left-footed dance partners. Belts, hats, bags and other accessories, such as sprays of artificial flowers, ruffs, muffs, collars and cuffs, were also coordinated, as were fabric-covered buttons.