- The once niche New York trend has become a dominant form of culture and a huge influence on high fashion – but there are still those not getting their dues

Hip hop has come a long way over the past 50 years, from humble New York roots to dominating global youth culture, and it will be hard to escape the half-century celebrations this year.

Questlove – The Roots’ drummer and beloved DJ – curated a 15-minute medley with some of the biggest names from hip hop’s half centenary at this year’s Grammy Awards, and 2022’s Super Bowl half-time show, arguably the biggest gig on the planet, featured west coast luminaries Snoop Dogg and Dr Dre, joined by Eminem and 50 Cent.

Then there’s the new four-part documentary Fight the Power: How Hip Hop Changed the World, airing on the BBC and PBS. In New York, the Fotografiska museum is showing “Hip Hop: Conscious, Unconscious”, a 200-strong collection of street fashion and iconic rap photographs.

Now a billion-dollar business, the music and culture hip hop birthed are a long way from its genesis on August 11, 1973, in the recreation room of an apartment building at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, in the Bronx, New York, when Cindy Campbell put on a “Back to School Jam” with her older brother, Clive, aka DJ Kool Herc, behind the turntables.

Cindy, who wanted to raise money to buy clothes for school, charged 25 cents for girls and 50 cents for boys (a handwritten invitation to a similar event, in February 1974, sold for US$27,720 at Christie’s’ “DJ Kool Herc & The Birth of Hip Hop” auction in 2022).

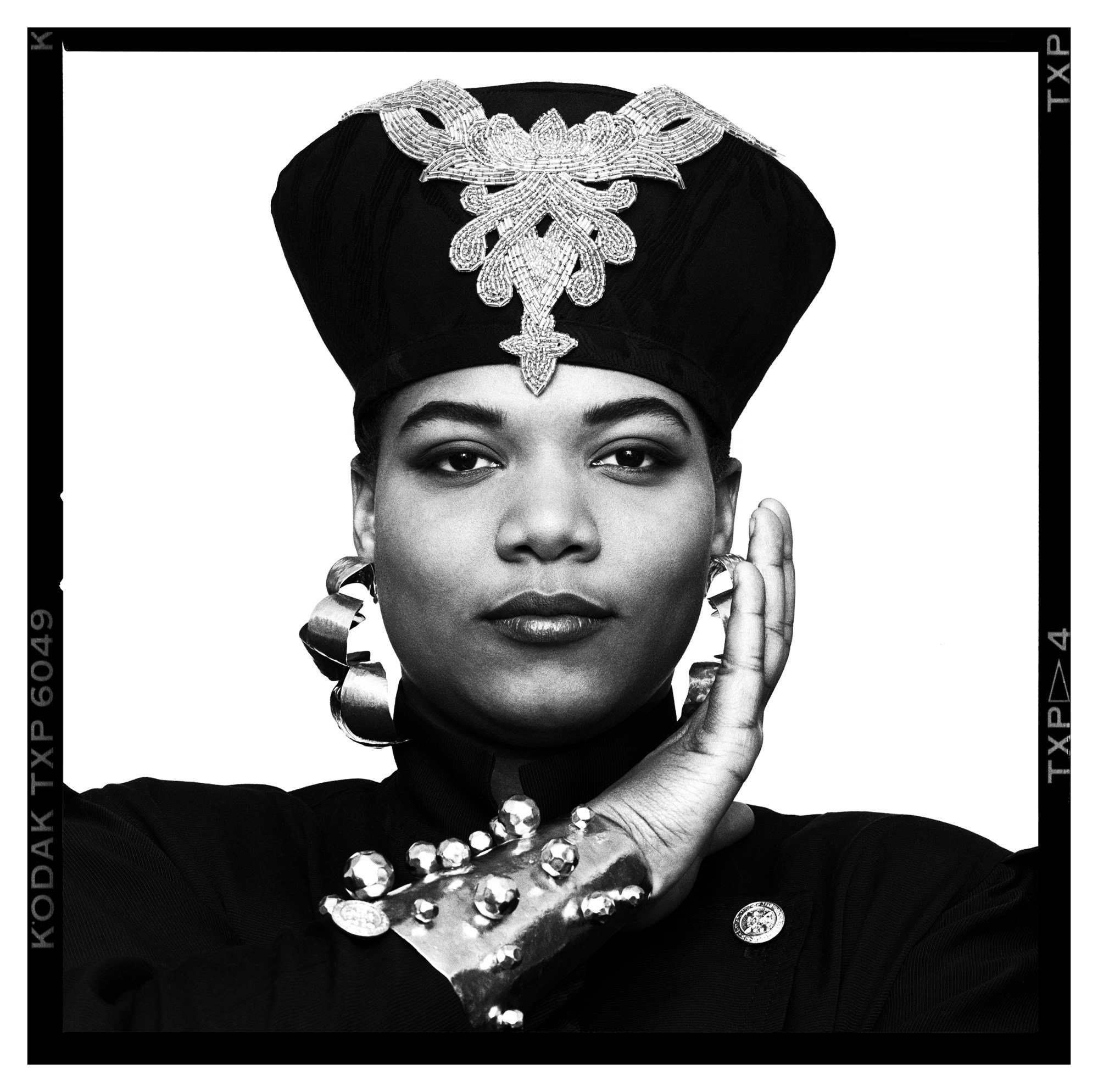

From that rec room came the five elements of hip hop – emceeing, DJing, breakdancing, graffiti and beatboxing – but there is an unnamed sixth element, fashion, which is being celebrated at the “Fresh, Fly and Fabulous: Fifty Years of Hip Hop Style” exhibition at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT).

“Style is definitely an unnamed element of hip hop,” says co-curator Elizabeth Way, associate curator of costume at The Museum at FIT. “The other elements all embraced fashion,” from graffiti jackets, early B-boy athleisure and all that garb that contributes to the peacocking of MCs and DJs.

Fashion is a cultural signifier, says fellow co-curator Elena Romero, an assistant professor and assistant chair of marketing communications at FIT. “Fashion is responsible for expressing what we believe, how we feel and, most importantly, being seen.”

Hip hop, more than other art forms or cultures, has long been obsessed with image, from the lyrics of early rap records to today.

“Being fresh is more important than having money,” rapper Kanye West, who now goes by the name Ye, states at the beginning of the 2015 documentary Fresh Dressed. “The entire time I grew up, it was like I only wanted money so I could be fresh.”

‘No space for us’: black hip hop artists help the scene grow in Hong Kong

While hip hop style has often been aspirational – see the legendary tailoring of Dapper Dan of Harlem using illicit logos of fashion houses such as Gucci and Louis Vuitton or knock-off versions of those big names – 1980s and ’90s high-fashion brands long kept their distance from the young men and women of hip hop, not wanting to associate themselves with the demographic.

Rap records and rappers were scapegoated by United States Republicans in that era and associated with criminality for their lyrics. The association extended to fashion, with the Polo Ralph Lauren-obsessed rappers among the Lo Lifes telling tales of “boosting” clothing from Manhattan stores, or the Notorious B.I.G. rapping about robbing someone for their North Face jacket.

A watershed moment came in 2004, when hip hop producer and sometime rapper Sean Combs (also known as Puffy, Puff Daddy, P Diddy) was named menswear designer of the year by the Council of Fashion Designers of America.

His Sean John label was part of a movement of hip hop clothing brands such as FUBU, Rocawear and Phat Farm, some backed by rap record labels.

Nowadays, luxury fashion shows have been soundtracked to rap songs that shout out the brand.

“Hip hop is in the very fibre of the fabric of luxury wear,” says K. Tyson Perez, a former stylist and designer of his HardWear Style brand.

“You have luxury brands like Louis Vuitton and Balenciaga sending complete streetwear looks down the runway. Hip hop is definitely embedded in fashion at every angle, even at The Gap.”

“Inevitably, what hip hop has started, mainstream culture has adopted, adapted and appropriated,” states the FIT exhibition introduction.

Appropriation remains a hot topic as hip hop style has become the mainstream.

“Today’s consumers are both judge and juror as to whether fashion companies are demonstrating cultural appreciation – a celebration of culture – or cultural appropriation – a total rip-off of culture,” says Romero.

“They are hyper aware of this and are quick to call out companies that profit from historically marginalised communities.

“For companies to avoid these pitfalls, they must do their homework, give credit where credit is due and be authentic and committed to the cultural investments they pursue.”

Perez has direct experience of Givenchy copying his zipper hat design, for example. “It wasn’t until I called them out on it, then they wanted to backtrack,” he says.

The Bronx-born designer believes that the threat of social-media uproar has seen brands give more credit to where they take inspiration from, rather than passing ideas off as their own, but even with the nods, those in the original culture are not seeing a share of the profits.

“They’re presenting it as an homage but it’s an homage that you’re profiting from and the people that you are taking from are not profiting the same way,” he says. “Fashion has changed slightly for the better [but] I believe a lot of it is performative, fashion is all about keeping up appearances, right?”

Rappers could also do more for the culture by mentioning labels other than the biggest luxury houses to receive “validation that they are rich”.

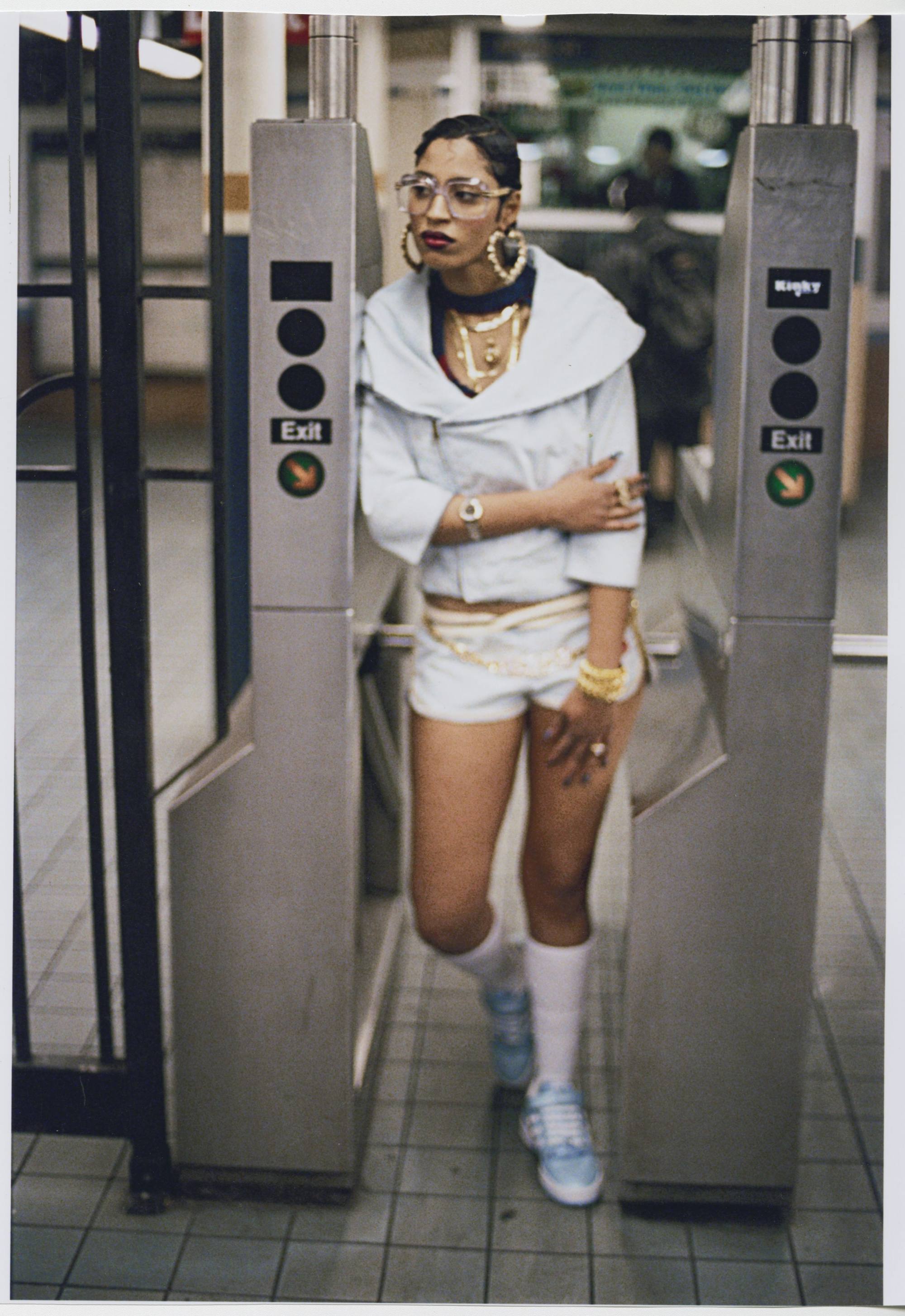

“Hip hop has always been about being flamboyant, about the biggest gold chain, the fattest laces and the sneakers, the sheepskin, the four-finger rings,” says Perez of classic hip hop fashions, many of which are on show at the FIT exhibition.

For co-curator Way, meanwhile, “I love the ensembles lent by individuals that showcase their personal style as devotees of hip hop during the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s. These people were B-boys, photographers, and students – people who just loved hip hop and showed that through their dress.

“They held onto their outfits and we are so lucky to be able to show them in the exhibition.”

Romero points out Chance the Rapper’s 1990s Polo Stadium collection-inspired suit from the 2021 Met Gala as a highlight. “It’s about being flamboyant, and fashion right now is all about flamboyant.”

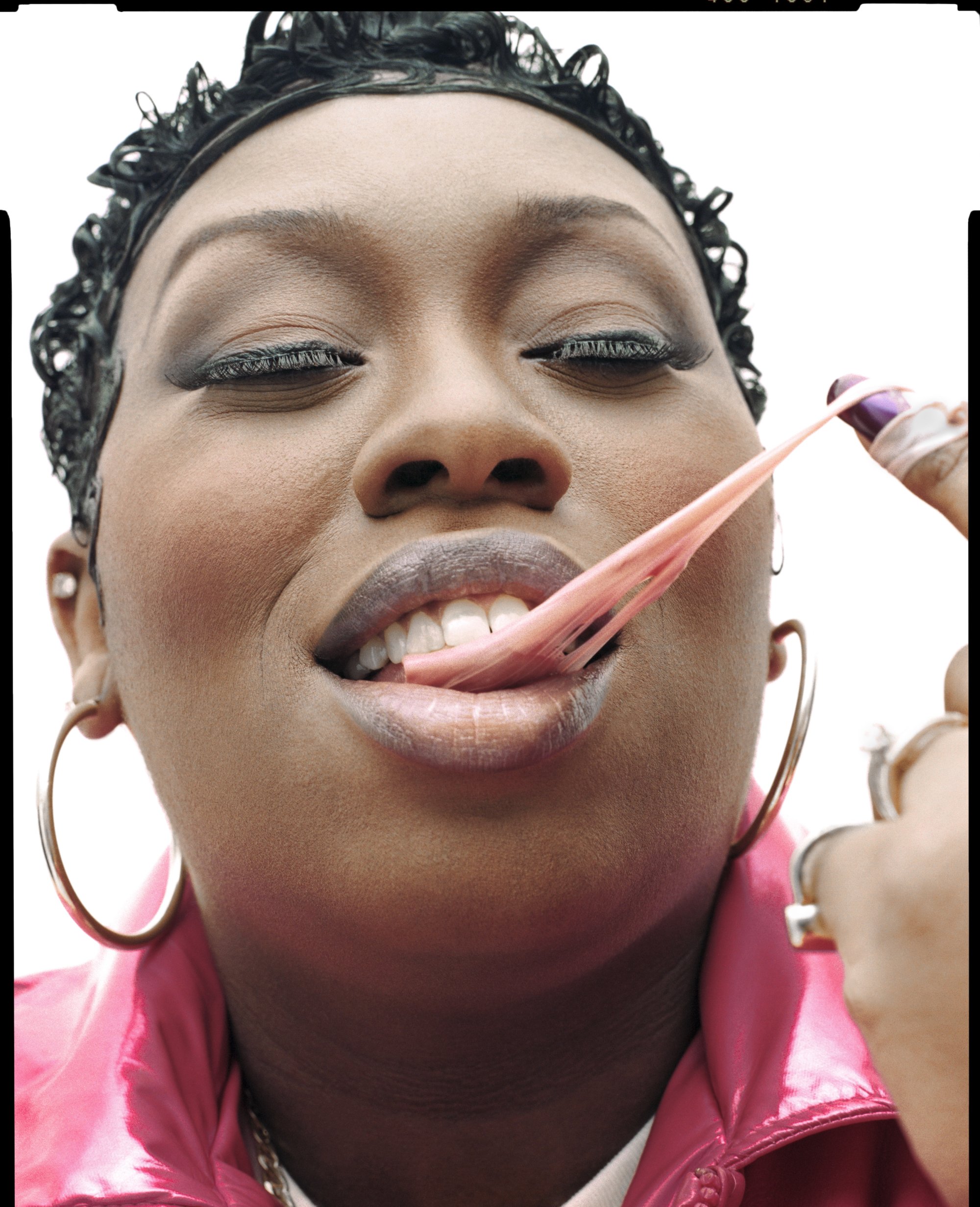

Athleisure, logo-mania, streetwear and nail art are just some of the style movements that have been greatly popularised by hip hop, says Way.

“With each generation,” adds Romero, “hip hop style gets reinterpreted and recreated locally and around the world. It’s what keeps it fresh, alive and well.”

“To me, hip hop says ‘Come as you are,’” DJ Kool Herc writes in the introduction to Jeff Chang and Dave Cook’s 2021 book on hip hop, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop. “It’s about you and me, connecting one to one. That’s why it has universal appeal.”