Recipe book: non-fancy dishes for a Chinese emperor

Su Chung's Court Dishes of China - The Cuisine of the Ch'ing Dynasty features dishes such as steamed carp, and five-spice pork liver, and are not as elaborate as you might think, writes Susan Jung

Anyone who thought the life of a Chinese emperor meant a life of leisure - extravagant meals, walking through the magnificent rooms and grounds of the Summer Palace, and consorting with concubines, with maybe an hour or two each day spent putting the royal stamp on edicts composed by ministers - is in for a surprise with this book. It offers glimpses of Qing dynasty court rituals that are as interesting as the recipes.

"No one in any dynasty of China ever lived a more rigidly controlled court life than the emperor of the Ch'ing. Due to strict observance of traditional conventions of the court, the freedom of the emperor was far less than that of an ordinary man," writes Su Chung (the name given to Japanese-American Yokiko Toshima, when she married a man whose family had close ties to Emperor Puyi) in this book, first published in 1965. "When he lived in the Imperial Palace, he had to rise at four o'clock. This early rising was called ch'ing chia, meaning, 'Your appearance is begged in court' … [The emperor] proceeded to attend the early audience which he gave to courtiers daily … From his chambers to the hall he rode on a palanquin, four guards in front and several eunuchs in the rear, and returned in the same manner. He slept again until seven o'clock and at nine he had breakfast … The only amusements the emperor could enjoy in the court were to attend a stage show, to practice calligraphy, and to paint. No other amusements were permitted …

"As long as the emperor stayed within the court, he was restricted in every way by tradition. Consequently, it was only natural that the emperor wished to stay away from court as much as possible. When the emperor lived in a detached palace, he could lead a comparatively free life, for he was exempted from the early-morning audience, he could dine with his consorts, and every manner and custom was simplified. Nevertheless, he was not as free as an ordinary person, for he still had to give daily audiences and promulgate instructions considering the documents submitted to him."

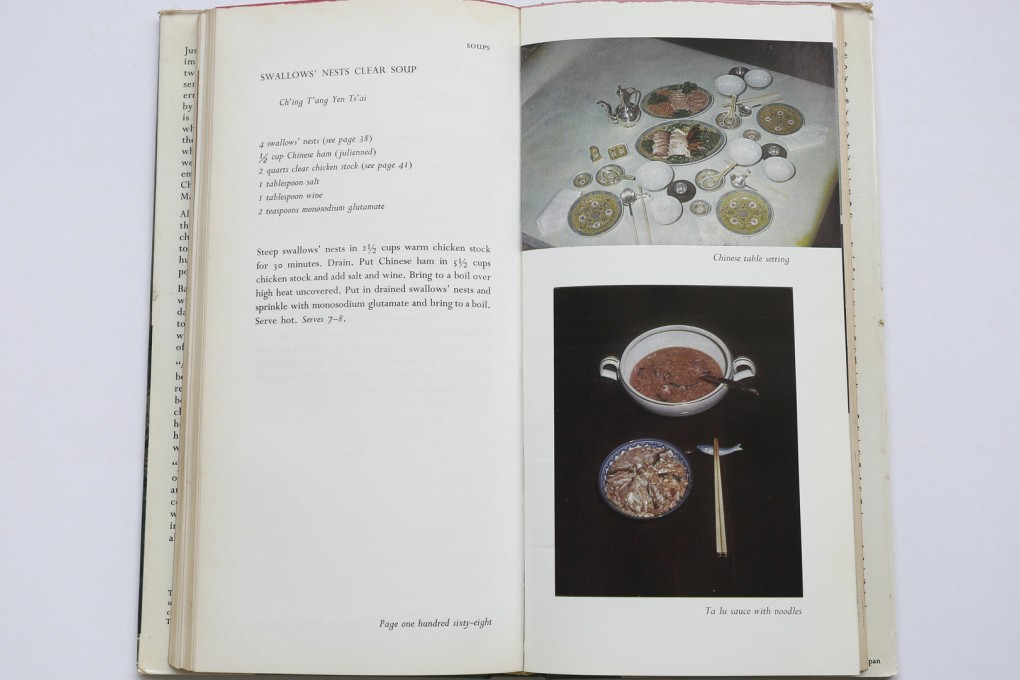

Bureaucracy, formality and tradition extended to the food the emperor ate.

"Meals for the emperor were not as fabulous as is generally imagined by outsiders, but the system of preparing them was on an extraordinarily large scale … The imperial cuisine consisted of five divisions: fish and meat, vegetables, roasts, refreshments, and rice. The divisions were divided into two sections, each having a chef and five cooks. In addition, each division included a supervisor, charged with watching over the cooks, and an accountant whose responsibility was the procurement of materials and the accounting for them …