Chef Roger Vergé’s cookbook has French recipes suitable for all abilities

- A proponent of lighter nouvelle cuisine dishes, Vergé’s recipes are divided into menus – some easy, others more difficult

- ‘The successful realisation of a menu depends on intelligent shopping – unless you are lucky enough to have a garden,” he wrote

French chef Roger Vergé seems larger than life as he admits to an enormous capacity for eating in the introduction to his book, Roger Verge’s Entertaining in the French Style (1986). “Some of these menus may strike you as overabundant, but they are scaled to my own appetite, which is not small,” he writes.

Fortunately for his waistline, Vergé was a proponent of nouvelle cuisine, which was a lot lighter than the cream-and butter-laden dishes of haute cuisine (Vergé died of complications from diabetes, however, in 2015, at age 85).

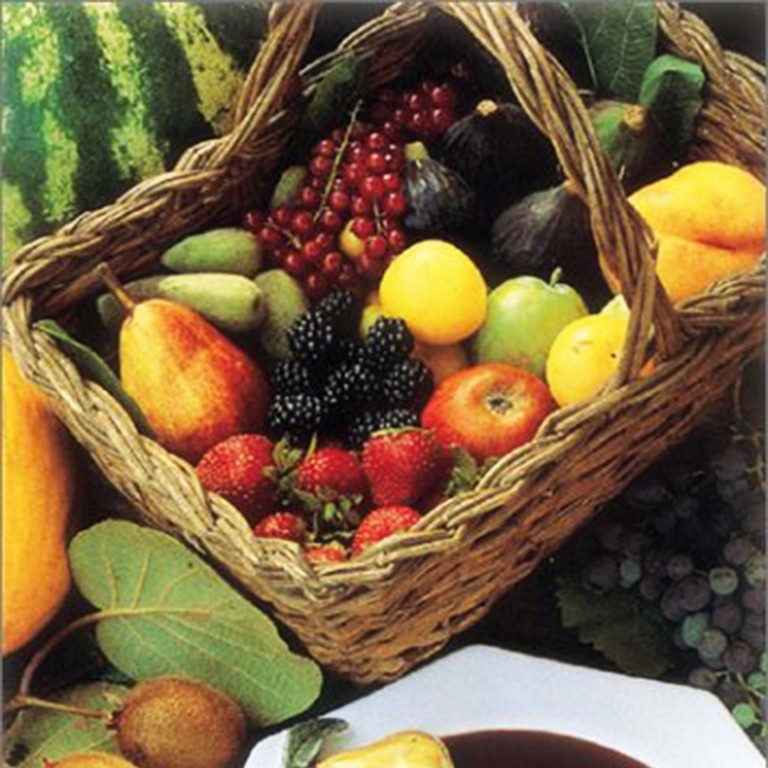

Like so many other great cooks, Vergé – who owned, among other restaurants, the three-Michelin-starred Le Moulin de Mougins, in Cannes – believed good food starts with good ingredients. “The successful realisation of a menu depends on intelligent shopping – unless you are lucky enough to have a garden. Nothing equals the aroma of freshly cut vegetables, fruits and herbs.

“At the Moulin, the gardener brings me fresh figs for the fricassée de volaille, but he has found uses for the leaves as well. In the back of the restaurant, the herb garden supplies an abundance of thyme, chives, chervil, and so forth.

“But if you don’t have a garden, you must learn how to shop. I was fortunate to learn this art in my early childhood, and that is probably what made me a chef.”

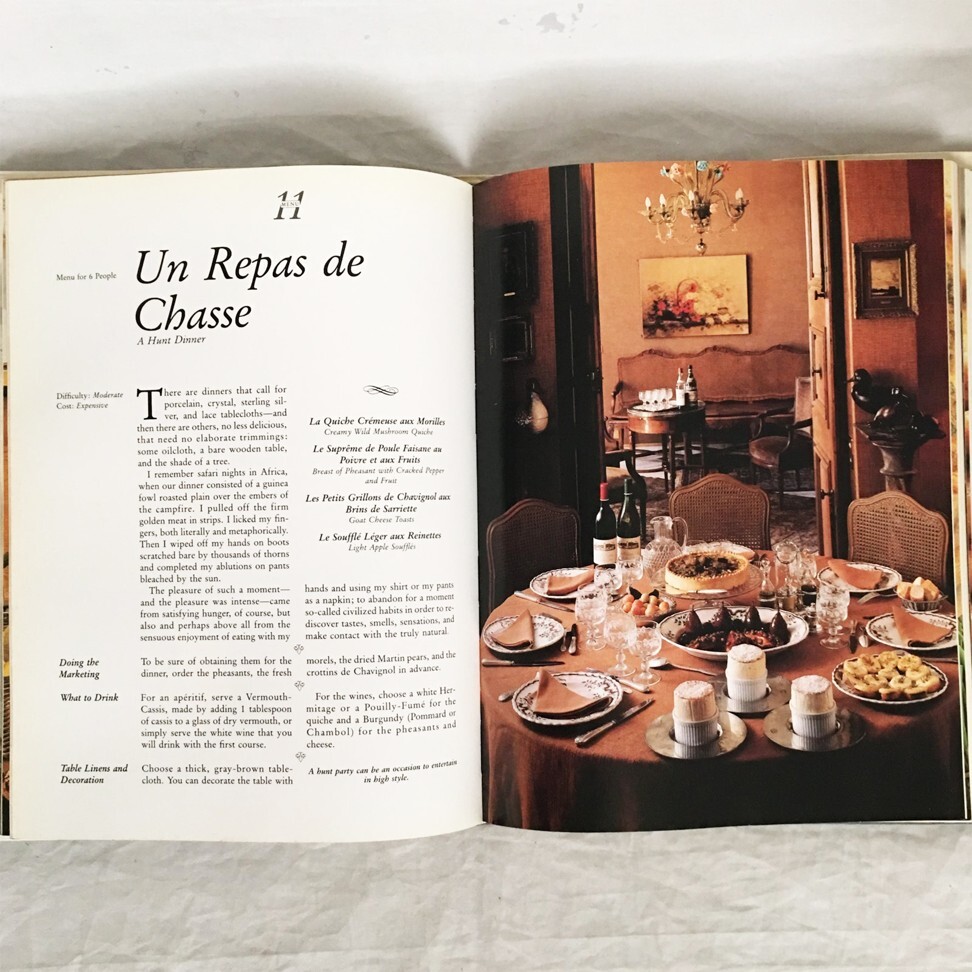

In the book, Vergé doesn’t just give recipes. He composes menus for different occasions, suggesting what to drink, what kind of table linen, decoration and tableware to use to set the tone, and giving tips on what can be prepared in advance and what needs to be cooked at the last minute. “I also offer all sorts of advice on giving your guests a relaxed and confident welcome,” he writes.

And he encourages the cook to “interpret” the dishes to please themselves, suggesting that those who want to (and can afford to) can add a pound of black truffles to a homely dish of grandmother Catherine’s chicken pie, as one of his recipe testers did.

The menus range from moderately easy and moderately priced to difficult and expensive, although keep in mind that Vergé’s idea of easy might not be the same as that of his readers. Among the former is a menu for “under the arbor”: roasted sweet pepper and anchovy compote, grandmother Catherine’s chicken pie, salad of chicory with hazelnut oil and tarragon dressing, dome of fresh cheese with green herbs, and seasonal fruit tartlets.

And the “at the bistro” includes recipes for Les Halles onion soup, chavignol goat cheese omelette, braised pig’s feet with roasted new potatoes, chicory and bacon salad, and individual apple and walnut tarts.

Difficult and expensive menus include “a grand occasion”: new potatoes with caviar, lobster and macaroni gratin, tomato and lime soup, heart-shaped hot quail pies with truffles and foie gras sauce, and individual vanilla soufflés with fresh fruit and armagnac sauce.