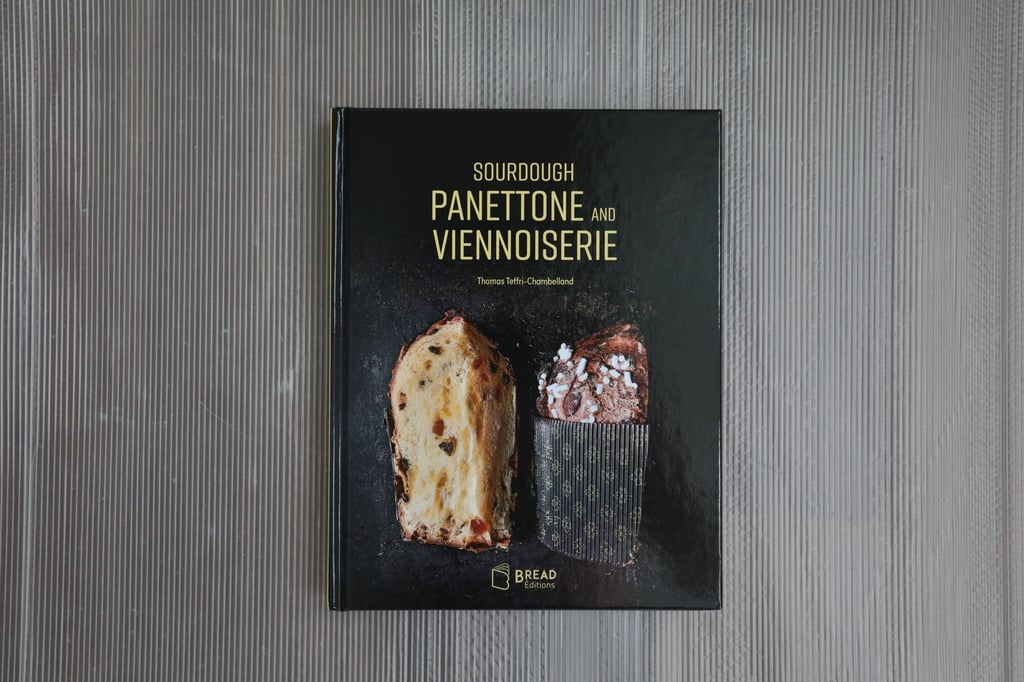

Sourdough Panettone and Viennoiserie: how the history of bread in France is ‘the story of people’

- In his 2020 book, Thomas Teffri-Chambelland explores how ‘celebration breads’ tell of people’s ‘joys and sorrows, their farming, their trading, and their social classes’

- It also includes recipes for Vesuvian apricot panettone, chocolate panettone, kugelhopf, croissants, Belgian cramique, brioche and more

If you’re one of the many home cooks who got into bread baking last year, during the pandemic, and panicked when stores ran out of commercial yeast, knowing that you could let your breads rise with a natural starter might have come as a revelation. But wild yeasts have been around since before our ancestors even began baking the first forms of bread.

As Thomas Teffri-Chambelland writes in the introduction to Sourdough Panettone and Viennoiserie (2020), “The purified yeast that is now used in nearly all bakery fermentations only became widespread in the early 20th century. This is an absolutely key point. It is important to understand that before the end of the 19th century, all bread dough, whether plain or enriched, was fermented with leaven. The products had virtually nothing in common with the ones we are familiar with today such as croissants and Parisian brioche.

“These items, which we call viennoiseries, appeared with the use of yeast. In a way, yeast brought them into being. So they are relatively modern products, having only been around for just over a hundred years.”

At its most basic, bread is composed of only three ingredients: flour, water and yeast or starter (we’re talking about leavened breads, as opposed to flat breads such at matzoh or tortillas, which don’t contain yeast).

Teffri-Chambelland, a biologist by training and founder of L’école Internationale de Boulangerie, in Noyers-sur-Jabron, France, does not cover these relatively simple breads in this book (he does in his previous two volumes, which are not available in English). In Sourdough Panettone and Viennoiserie, the author is writing about far more luxurious breads, ones eaten for celebrations. “For centuries, all over the world people’s daily bread was enhanced for celebrations by adding sugar, eggs, fat, or dried fruit depending on what was available […] No era or area of France is without its specialty celebration bread.