Then & Now | How the cutlet reached Hong Kong and Singapore from India, and its culinary cousins the ‘aloo chop’ and chicken chop – the latter still served today

- A cutlet in its basic form is a breadcrumbed, oval patty of minced meat, but every Asian subculture developed its own variety

- Largely gone from dinner plates now, it had a vegetarian version, the ‘aloo chop’, and a cousin, the chicken chop, that’s on Asian cafe menus to this day

Creolised cuisines are a permanent marker of Asia’s otherwise disappearing “crossover” societies. From the 16th century onwards, successive waves of Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, British and French arrivals – along with their latter-day American successors – all left their mark wherever they settled across Asia.

Over time, the most popular recipes from these communities, gradually altered by successive generations of their hybrid descendants, have become keynote dishes served at community reunions anywhere diasporic emigrant groups have appeared.

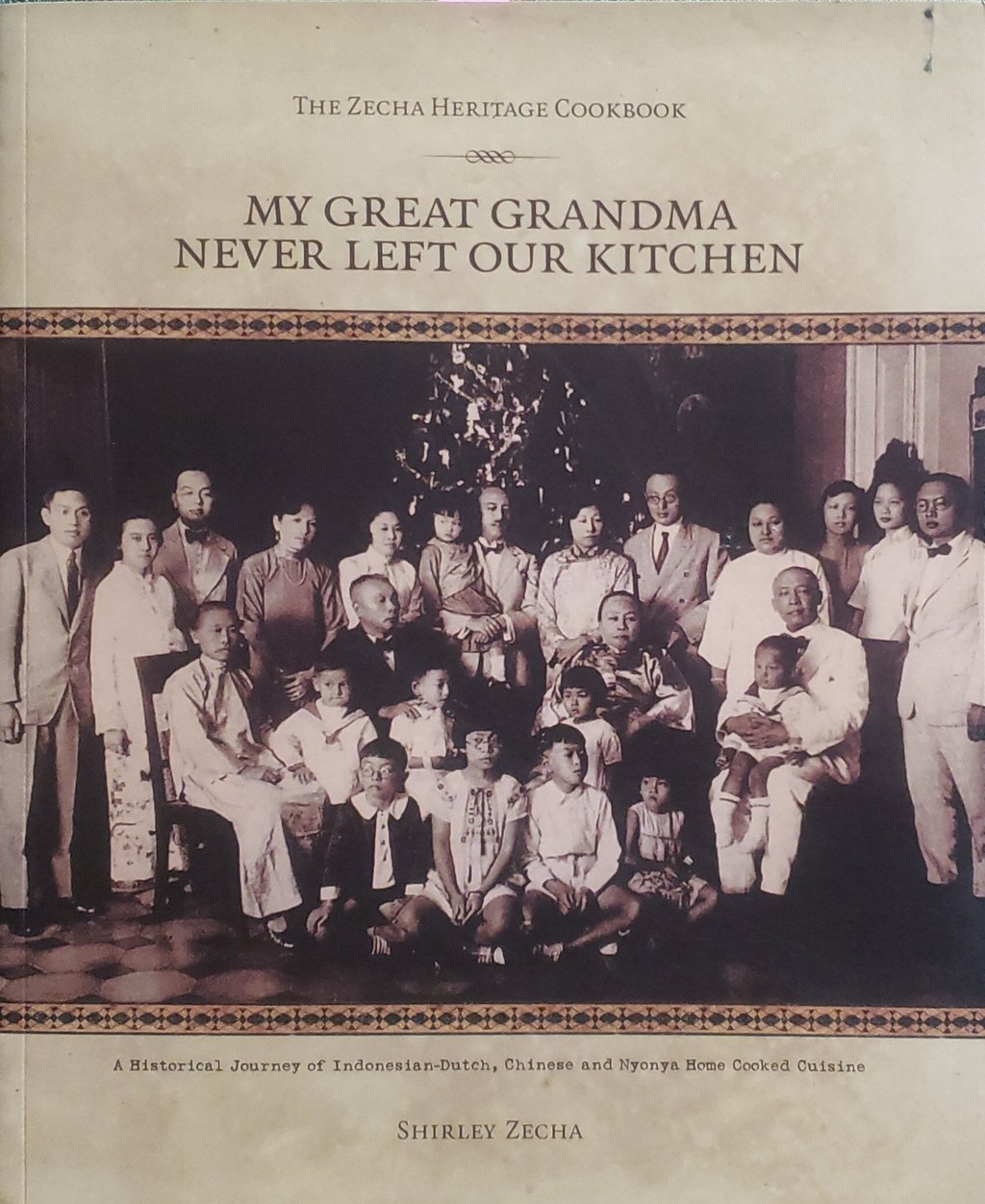

Traditional foods form the centrepiece of various nostalgic, heritage-themed recipe books, which have proliferated over the past couple of decades as older family members, with direct personal connections to original homelands from India and Indonesia to Macau and the Philippines, inexorably pass away and take their own living memories with them.

The best of these volumes artfully combine period photographs – often grainy due to poor interior lighting – with ephemera such as original kitchen equipment and recipe books, leavened with tantalising glimpses of otherwise hard-to-learn elements of social history.

Food preparation, after all, is among the most basic of human connections, long shared with members of one’s own group, and offered to others.