The rise and fall of the Hong Kong tailoring industry

With competition from fashion brands and a lack of fresh apprentice blood, things may not be so dandy for the city’s tailors, who only 50 years ago outshone Savile Row

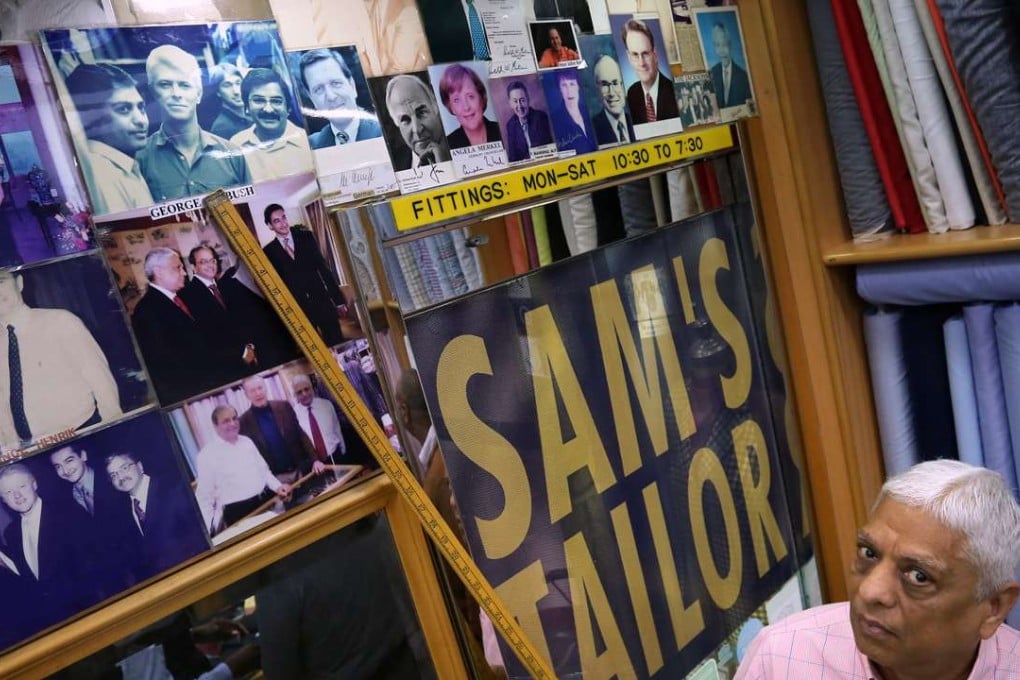

Hong Kong’s most famous tailor’s shop has been open for less than half an hour and customers are already standing shoulder to shoulder, being deftly measured by a platoon of men armed with tape measures.

Fifty years ago, there were an estimated 500 shops such as this in Tsim Sha Tsui and customers from all over the world, including political leaders, Hollywood celebrities and pop stars, beat a path to their doors.

On August 10, 1966, the South China Morning Post ran a headline announcing that London’s Savile Row, until then the undisputed international home of bespoke tailoring, had been overtaken by Hong Kong. The article suggested the city was now “the sartorial capital of the well dressed man’s world” – but much has changed in the subsequent five decades.

In an era of disposable fashion, with international brands dominating the men’s market, few young people are entering the industry and many fear the future of Hong Kong’s proud bespoke tailoring tradition is hanging by a thread.