The China gene genius: from Hebei to the pinnacle of American science

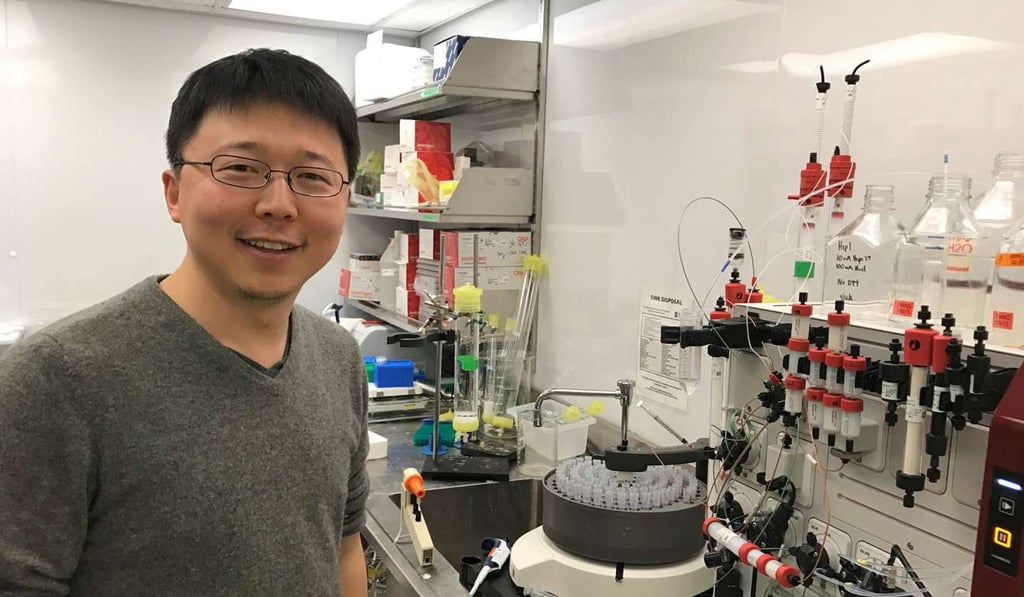

Meet the young China-born American scientist who is making waves with a technique that could roll back disease and usher in “designer babies”

Feng Zhang occupies a corner office on the 10th floor of the gleaming, modern biotechnology palace called the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the United States. He is one of the most acclaimed young scientists in the US, regularly mentioned, even at 35, as a possible Nobel laureate.

That’s because of CRISPR, the gene-editing technique that lets scientists manipulate the genetic code of organisms almost like revising a sentence with a word processor. Zhang was one of its pioneers, and last month he emerged victorious after a bitter patent dispute.

The ruling, by judges with the US Patent and Trademark Office, declared that Zhang’s work on living plant and animal cells was sufficiently original to deserve its own protection. It was a decisive outcome that will surely prove lucrative for Zhang and the Broad Institute, but he did not do anything special to celebrate. He made no immediate public comment. He did not even read the news coverage, he says.

“The patent stuff is not so interesting, and it can be distracting,” the soft-spoken scientist offers a day later, finally addressing the issue as he sits down for a previously scheduled interview. “Now we can get back to work.”

CRISPR is an all-purpose tool that promises great advances in the prevention of diseases caused by genetic mutations. In China, Zhang’s country of birth, it is already being used in human clinical trials.

Yet the technique has also raised unsettling possibilities for cosmetic human enhancements and “designer babies.” Last month, the National Academy of Sciences and National Academy of Medicine produced a report on the ethics of gene editing, arguing for extreme caution when dealing with heritable human traits but leaving open the possibility of use to remove disease-causing genes.