How China’s ancient carrot-and-stick concept guides its rise, and why it has just 15 years to secure its place in the world

Howard French, American China watcher, talks about Xi Jinping, Donald Trump, and his new book looking at how the nation’s rise accords with a concept it has long taken for granted – tianxia

“China’s policy [regarding] North Korea, the South China Sea or the big question of the day is driven by a sober assessment of whatever China’s national interests are. China has not cracked down on North Korea to the extent that one American president after another would like to have seen, not because China is recalcitrant or fails to understand American concerns; China has its own concerns, which are pre-eminent. That’s normal. That’s how countries work.”

So says American journalist and writer Howard French when discussing recent developments in Asian geopolitics. An associate professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, in New York, French is an excellent guide. His 20-year career as a foreign correspondent for The New York Times includes stints as bureau chief in Tokyo and Shanghai. His 2014 book, China’s Second Continent, explored the country’s imperial ambitions in Africa.

The follow-up, Everything Under the Heavens (2017), could not have been timelier if recent news headlines had been stage-managed by a publicist. An incisive, readable history of China’s foreign policy within Asia, the book focuses on the country’s fluctuating, often turbulent relationships with Japan, Vietnam, the Philippines and the Koreas. The historical scope is equally impressive, sweeping from Zheng He’s 15th-century maritime explorations to Beijing’s present-day ambitions in the South China Sea.

Nevertheless, so rapid is the speed of change in Asian realpolitik, in stark contrast to book publishing, that what seems up-to-date one minute feels archaic the next. Open the index of Everything Under the Heavens and one name is conspicuous by its absence – that of Donald Trump. French is sanguine about the omission; historical depth, not topicality, is Everything Under the Heavens’ raison d’être.

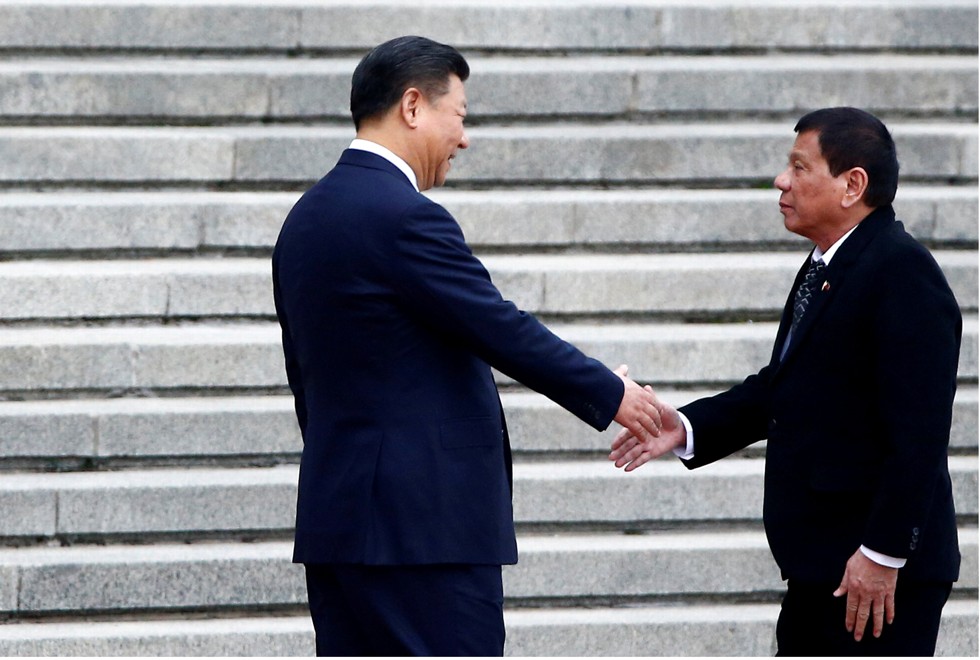

A book, unlike a journalistic article, simply can’t keep pace with breaking news. He cites the election of Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, which happened shortly after Everything Under the Heavens was completed, in the summer of 2016. Duterte’s arrival required small, if significant, additions to the text.

“Let’s just pray that nothing else really dramatic happens,” French recalls thinking at the time. “Then a few months later Trump gets elected president. Few people expected that, including Trump.”

Even if he’d had the time to assess the new American president’s early foreign policy stance, French isn’t sure what he could have said.

“There has been no grand elaboration of policy vision,” he says. “We don’t have any Trump doctrines about geopolitics or Asia.”

There was the famously obstreperous tone of Trump’s campaign, which included the accusation that China was raping the United States economically: “It’s the greatest theft in the history of the world,” he railed at one point.

French translates this aggressive tone into the language of Trump’s “Putting America First” spiel.

“There was a lot of rhetoric about the limited or even negative value of alliance for the US,” says French. “Bilateral relations are going to be the name of the game. That strikes me as a disastrous approach to international affairs on many levels – politically, economically, militarily, in terms of security.”

Nonetheless, French does detect reasons for cautious optimism in what he calls Trump’s “rapidly evolving presidency”, or “a more thorough-going coalescing of a world view in this man who has no prior experience in anything like political leadership”.

There was the seemingly affable summit in Florida with President Xi Jinping last month.

“One can be comforted on the one hand. Trump and Xi in a superficial way seemed to get along well,” says French. “Trump clearly abandoned a lot of his hostile language towards China and his crude, rough-edged formulas that he had thrown around so loosely during the campaign.”

At the same time, examples of Trump’s inexperience on the global stage were all too evident.

“When I hear Trump saying, ‘If China takes care of North Korea, then we will give them a better trade arrangement,’ I can’t help but think that this is quite a naive understanding of how the world works.”

French’s own understanding of China began in childhood. He heard stories about his African-American grandfather, who admired what he perceived as China’s sense of national superiority.

“As a boy, I experienced these stories the way most [African-Americans] would: the thought that there could be a people that think of themselves as fully the equals, and maybe the betters, of Westerners really impressed me as a boy,” he says. “East Asia is proof that white superiority is baseless – that there is no reason why the current racial hierarchy that one imagines in the world would persist, or that one should even give credit to it.”

French developed this interest as an undergraduate at the University of Massachusetts in the mid-1970s.

“I was a political science major in college and read a lot about China then. This was towards the end of the Cultural Revolution and I was fascinated by Mao Zedong, and, indeed, admired him as a leader and revolutionary and strategic thinker. Of course, the picture that most outsiders had of events in the country, at least since the late 50s, was very incomplete.”

His father’s work for the World Health Organisation saw the family relocate to the Ivory Coast. In 1979, French worked as a translator (between English and French) in Abidjan, before teaching English literature at the University of Abidjan, until 1982. His journalism career also began in Africa: as a freelance reporter for The Washington Post, before he joined The New York Times in 1986.

For the best part of the next two decades, French served as bureau chief in various locations: from the Caribbean to Central America to Pakistan. He was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for his writing about Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), covering the fall of dictator Mobutu Sese Seko.

French, who was The New York Times’ Shanghai bureau chief from 2003 to 2008, describes the experience of working as a foreign correspondent in China as “nothing unusual”. For example, when he covered the Dongzhou protests in 2005 – organised in opposition to government plans to fill in a bay and build a power plant in the Guangdong village – “The entire area [...] was cordoned off to prevent press access,” he says. “To be able to report on events there required lingering on the perimeter and finding local residents who were still coming and going.”

French’s work in Asia began in Tokyo, where he reported on Japan and the Koreas, before moving to Shanghai. He had first visited China in 1999, as a fellow of the East-West Centre.

“I had just spent a year in preparation for assignment to Japan, and I had been working hard to learn that language,” he says. “I had no idea at the time that I would eventually go on to cover China.”

French landed in Beijing within days of the US bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, during an international effort to stop Yugoslavian president Slobodan Milosevic’s assaults on Kosovo.

“The streets near the hotel where I stayed in Beijing were full of student protesters,” French says. “We were warned to avoid them, but I wandered around and was not subjected to any direct hostility.”

French’s intention in Everything Under the Heavens, as he puts it, is “to normalise China”.

“‘Normalising’ China means saying that China isn’t alone in having its own culture, history and ambitions,” he says. “I don’t want the reader to think I am being alarmist, or making the case for some deep Chinese exceptionalism. Britain has a history. So does America, France, Russia. Normalising means understanding [China] is one story among others.”

What are China’s neighbours and the Chinese public to make of two small, ethnically Chinese societies, Hong Kong and Taiwan, that don’t want Chinese authority? This is too glaring an insult for China

China’s story just happens to be intimidatingly vast and complex, which partly explains French’s decision to filter its history through a central concept: tianxia, an ancient Chinese cultural concept that gives his book its title. The literal translation of the word is “everything under heaven”.

What tianxia means in practical political terms, French writes in the book, is “China’s tribute system”.

“Tianxia emerges as a paradigm for China’s geopolitics from a correct sense that it is vastly larger and, for most of its history, vastly richer than any neighbouring state,” French explains during our conversation. “Out of this flows an ideal, from the Chinese perspective, that order can best be established in our neighbourhood by a situation whereby the neighbours defer to us.”

In the most technical sense, deference is expressed through a highly ritualised series of ceremonies: embassies dispatched to pay obeisance to the emperor; the adoption of the Chinese calendar and language. In broader policy terms, tianxia combines carefully deployed “sticks” and “carrots”. French points to historical evidence to argue that China uses inducements first and force only as a last resort: the Sino-Vietnamese war of 1979 is an example. Carrots include access to Chinese trade, to its potentially vast market, and to what French describes as “patents of authority. China essentially legitimates local leaders by endorsing them”. On this basis, “a harmonious pattern of coexistence can endure in the region. One could say only on this basis”.

“China didn’t say, ‘You are infringing upon tianxia’, but that’s very much what was going on,” French says. “[China says] ‘We control those waters. You should get with the programme and defer to us.’”

After Duterte’s conciliatory gestures during his China visit in October, Beijing responded in classic tianxia fashion by offering US$24 billion in investment and financing deals.

“China astutely begins to ply inducements to arrive at a situation whereby the new president, to most people’s surprise, tables the Philippines’ legal victory and gets back on the boat with China,” French says. “This is tianxia brought up to date.”

One factor that distinguishes 21st-century tianxia is China itself. Now extremely powerful economically, it is seeking to correct what French calls “a century of national humiliation” at the hands of colonising Western and Japanese powers. He sees the rebirth under Deng Xiaoping, expressed through his famous 24-character strategy from the early 1990s, as promoting a more modest form of tianxia: “Hide our capacities and bide our time […] Never claim leadership.”

That moment, French argues, arrived in 2012, with the ascent of Xi.

“The first thing Xi did was announce this theme of rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation: the ‘China dream’. That very much involves restoring Chinese prerogatives of a tianxia sort in the immediate neighbourhood.”

One consequence of Xi’s recalibrated tianxia is Beijing’s relationship with Hong Kong. French has written at length about the challenges posed to the territory by the economically and politically dominant mainland. Viewed in a context of tianxia, he says, Hong Kong, like Taiwan, is an anomaly.

“The norm for China is to loom pre-eminent in its immediate neighbourhood. What are China’s neighbours and the Chinese public to make of two small, ethnically Chinese societies that don’t want Chinese authority? This is too glaring an insult for China to allow such a thing to come to pass. China is hell bent for this reason on bringing them to heel, to make sure they are not only reinserted into the fold, but they abandon any notion of separation, in a psychological or political way.”

The tianxia carrot is mainly financial.

“As the economic balance has shifted so heavily in Hong Kong’s disfavour, the carrot is finding ways of keeping the territory flush with money,” he says.

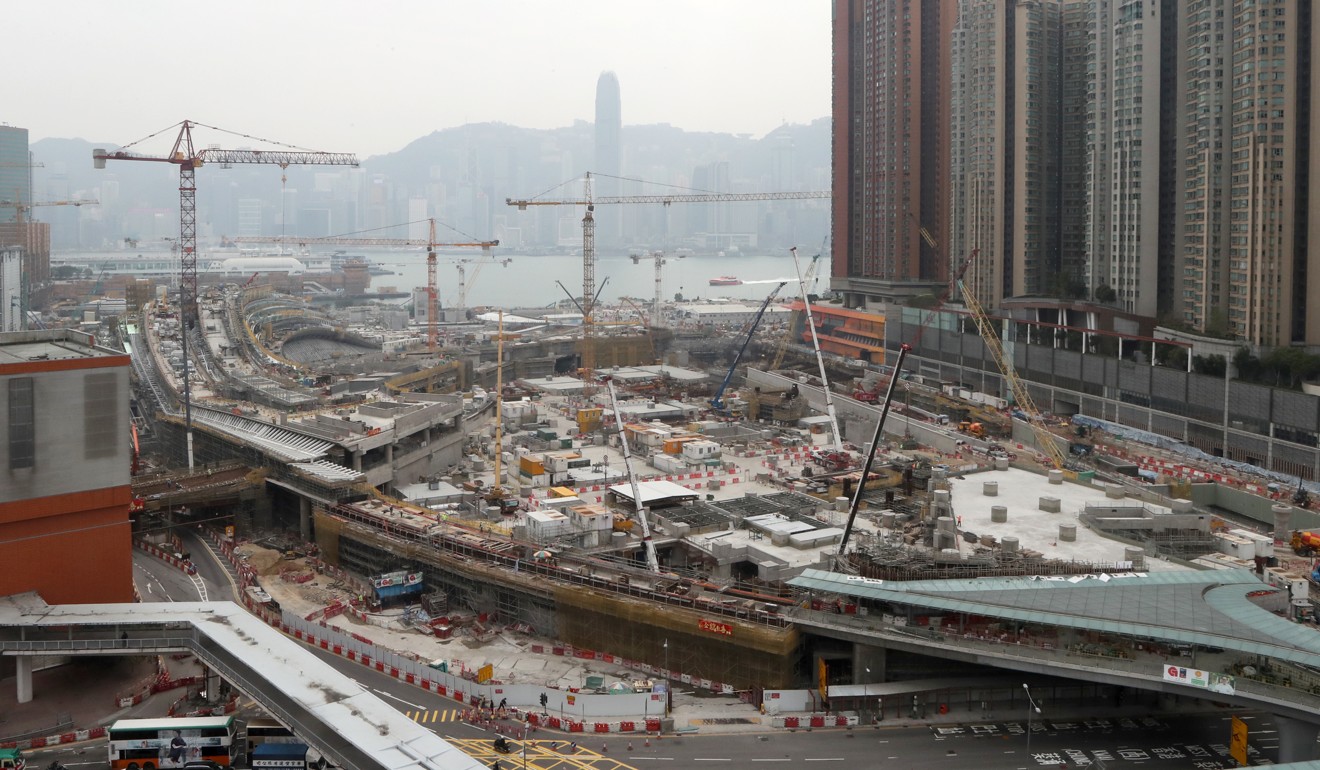

French sees the efforts to integrate Hong Kong into China via immense infrastructure schemes in the Pearl River Delta as one way of this happening.

Another is the transference of economic power.

“China can liberate markets in places like Shanghai and Tianjin and send the message to the world that this is where East Asia’s great financial transactions should be conducted. This will pull the rug out from under Hong Kong.”

French doesn’t believe China wants to do either of those things, but that doesn’t mean it won’t.

“The carrot part it is doing. The stick part looms, and everyone knows it.”

Britain has been noticeably muted of late when it comes to criticising Beijing’s relations with Hong Kong, whether its alleged interference with democratic elections or the city’s publishing industry. Is this an example of tianxia spreading into Europe? Is Britain showing deference to the new superpower?

“From the Chinese perspective, Europe is a bunch of very small countries that can be played off against one another,” French says. “This is one of the central ploys of the tianxia playbook. Britain, as the least European, has always seemed to the Chinese as perhaps the most susceptible to this kind of thing, the easiest to pick off.”

These suspicions have only grown following Brexit.

“The British leadership feels it needs to score some kind of gain in terms of trade relationships to show that Brexit is not going to be a total disaster. China is awake to this and will find ways to play its advantages vis-à-vis a disaggregated Europe.”

Nevertheless, French does offer words of caution about the sustainability of such an approach.

“For all of China’s startling recent show of ambition and assertion, there are many reasons to think that this is a special phase,” he says. “We should not plot a direct graph line from the last 10 years and then extrapolate.”

China’s future progress faces an obvious impediment.

“Demographics are the key challenge to China over the next three to four decades,” he says. “China’s response is going to be the main determinant of where it ends up in the geopolitical scheme of things.”

By 2050, an estimated 400 million people in China will be over the age of 65.

“The ratio of [young to old] is going to tilt dramatically and on a scale we haven’t seen before in history.”

Other nations – Japan, Italy, Russia – are ageing with commensurable speed, but they have the advantage of smaller populations, higher levels of per capita income and superior social-security systems in place.

“You are going to see young Chinese couples who have four living parents turn to the state to help provide for their elderly relatives. This is going to create a burden on the Chinese state and the Communist Party that will become absolutely decisive.

“This partly explains why Xi appears to be in such a hurry. He understands that China has a small and narrow window of opportunity on the global stage to push for the locking in of its prerogatives.”

French cites the assertiveness in the South China Sea, the development of “One Belt, One Road” and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

“In 15 years at the outside, the demands of taking care of the ageing will simply make it impossible to create big new initiatives like these. Do it now, lock it in and pivot your attention after Xi has moved on to this big ageing avalanche that is about to hit China.”

This avalanche will hit no matter what. One consequence of failing to deal with this demographic time bomb would be China’s having to choose between its global ambitions and domestic stability.

“If things break the wrong way – an economic crisis, for example – or if China simply muddles along and doesn’t attend to the demands of caring for the ageing, it could be sufficiently profound to force a very dramatic inward turn.”

For Beijing, the choice is not between guns and butter, as macroeconomic theory puts it, but guns and canes.

“The political legitimacy of the Communist Party is going to depend very much on how it negotiates this. There are those that wish to push for greater Chinese assertion in East Asia, and perhaps more widely. And there will be those who say, ‘That way lies ruin’ – meaning revolt. Revolt because too many grandmas are dying in the tiny back rooms of crowded houses and not being cared for in nursing homes.”

If you want a worst-case scenario, Everything Under the Heavens provides one from the late-15th century. Approaching the height of its power, China retreated from the world stage, dismantling its shipyards and citing Confucian ideas of self-reliance at the precise moment that the world began looking outwards. In the book, French describes this as “one of history’s greatest turning points – or as some have characterised it, greatest blunders.”

Could a similarly profound shock cause China to withdraw from the global stage once again?

“If [the demographic challenge] is mismanaged, it will be as profound as that. The key is managing it well enough now so that China doesn’t have to make too absolute a choice between pushing for international benefit and prerogative and turning inward to take care of this huge population problem.”