Can Taiwan’s Formosan clouded leopard claw its way back from extinction?

With no confirmed sightings of the big cat in decades, some question whether a Taiwan subspecies of the predator ever existed; it’s a question some say should be answered before captive clouded leopards are released into wild on island

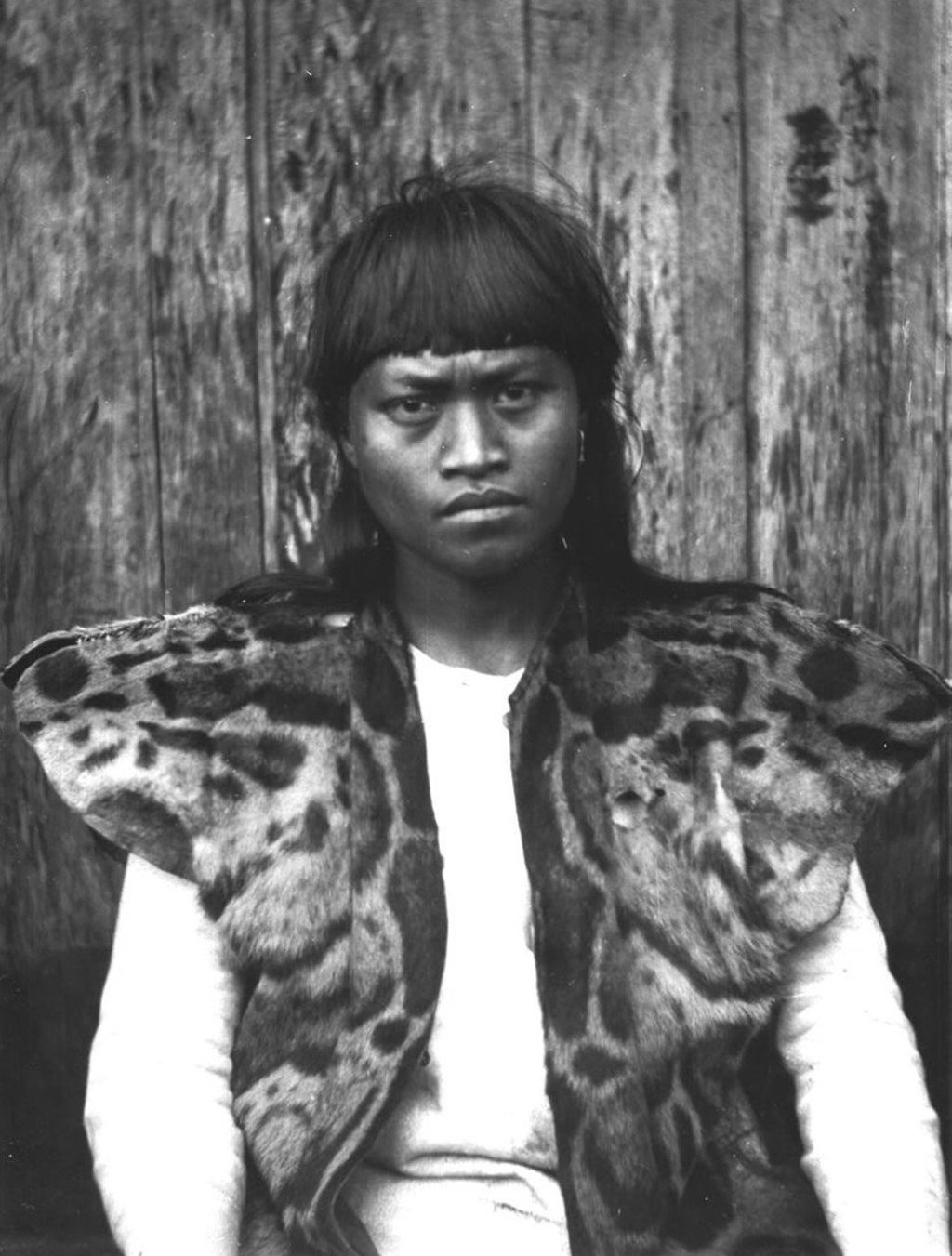

“This is another animal from the distant wilds of the interior, whose skins the savages bring to the borders to barter with the Chinese.”

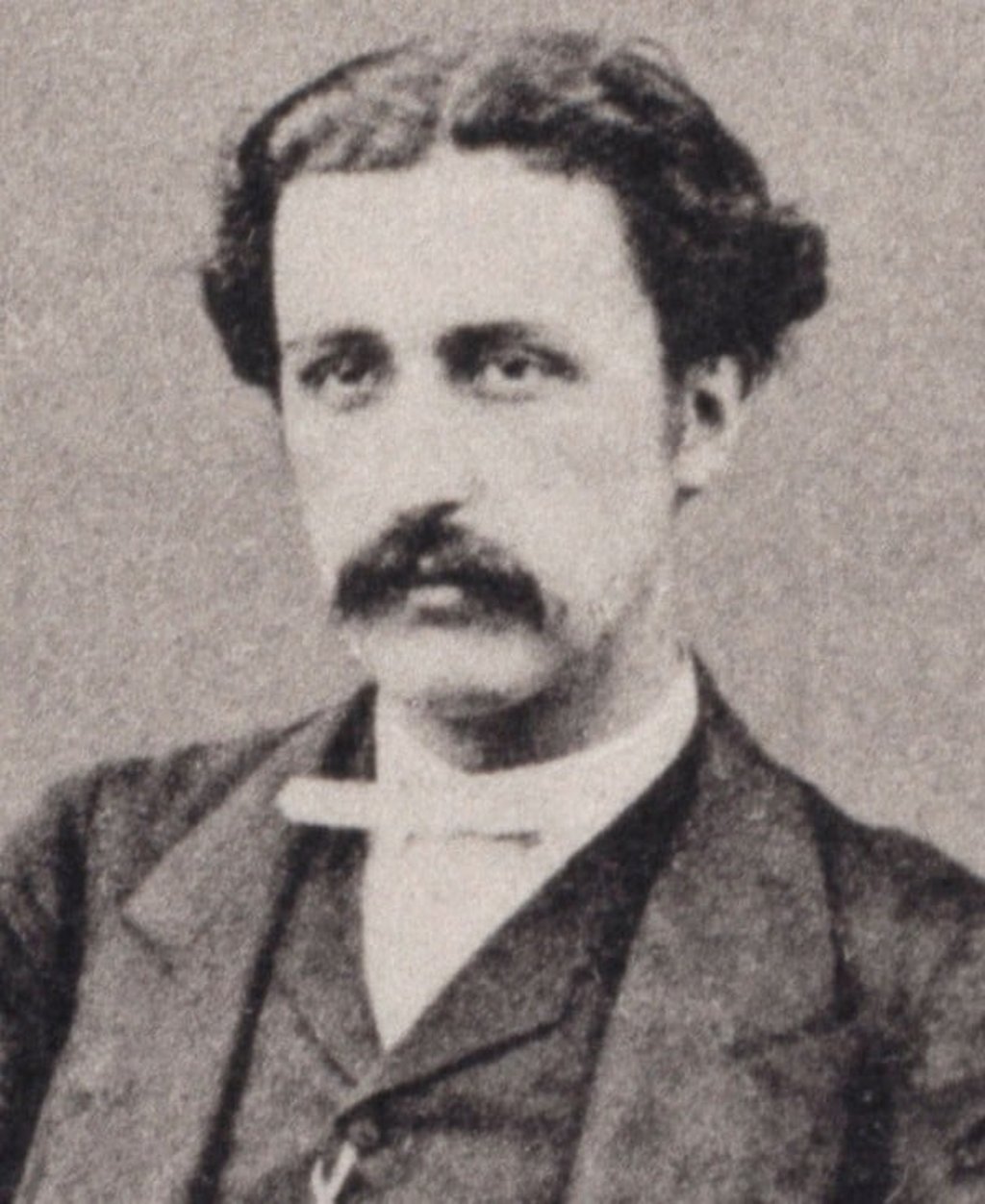

With these words, published in 1862, British naturalist Robert Swinhoe introduced the Formosan clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa brachyura) to the Western world. Europe’s consular representative to Taiwan, he had seen only a few flattened skins on the island, but this was enough for him to distinguish it as a species new to science. Unlike its relatives elsewhere in Asia, wrote Swinhoe, the Formosan clouded leopard had a short tail.

It was declared extinct in 2013, but this is no ordinary story about a big cat being wiped off the planet. There’s a catch. Plans are afoot to bring the svelte feline’s closest relative back to Taiwan – despite lingering questions over whether the Formosan clouded leopard ever existed at all.

Today, Asia is home to two species of clouded leopard: Neofelis nebulosa (clouded leopard), found across the Asian mainland, from the Malay peninsula to the Himalayan foothills of Nepal, and Neofelis diardi (the Sunda clouded leopard), found on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. Both are at risk of extinction and rarely glimpsed in the wild, even by those who study them.