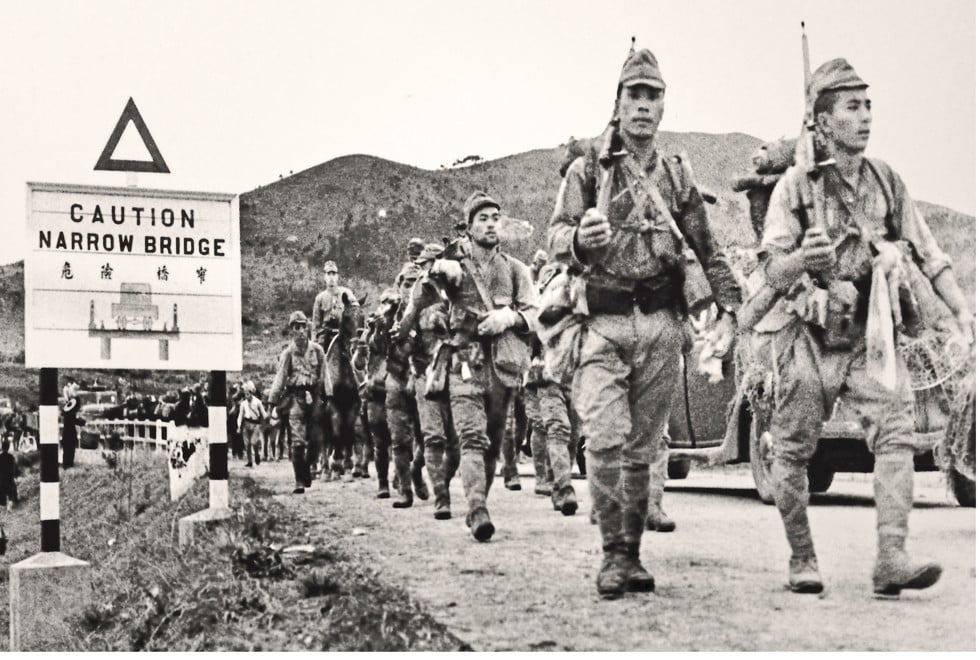

Witnesses to horror: the Allied civilians in wartime Hong Kong who watched, helpless, as Chinese starved at hands of Japanese

Fear, isolation and constant danger were the lot of Allied civilians initially spared internment in second world war Hong Kong, but that was nothing compared to the atrocities Japanese perpetrated on city’s Chinese population

Soon after dawn on Sunday, May 2, 1943, a contingent of Japanese marines made a dramatic entrance into the compound surrounding St Paul’s Hospital, in Causeway Bay. Behind them was a team of gendarmes from the Kempeitai – the dreaded “Japanese Gestapo”.

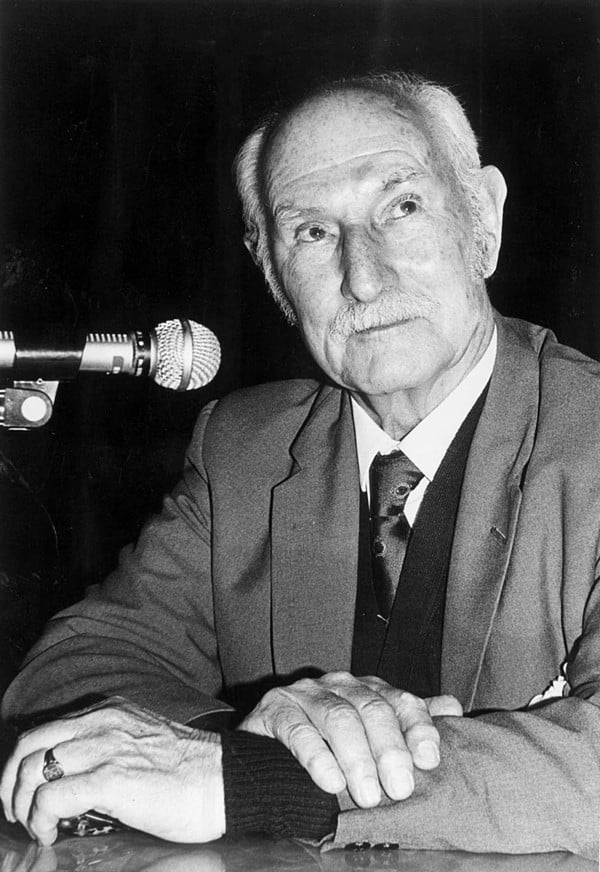

They had come to arrest Dr Percy Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke, Hong Kong’s former director of medical services, who had been allowed to remain outside the Stanley civilian internment camp to act as a public health adviser to the Japanese. The Kempeitai believed that Selwyn-Clarke’s medical work was a front for his role as leader of a British espionage ring sending information into Free China.

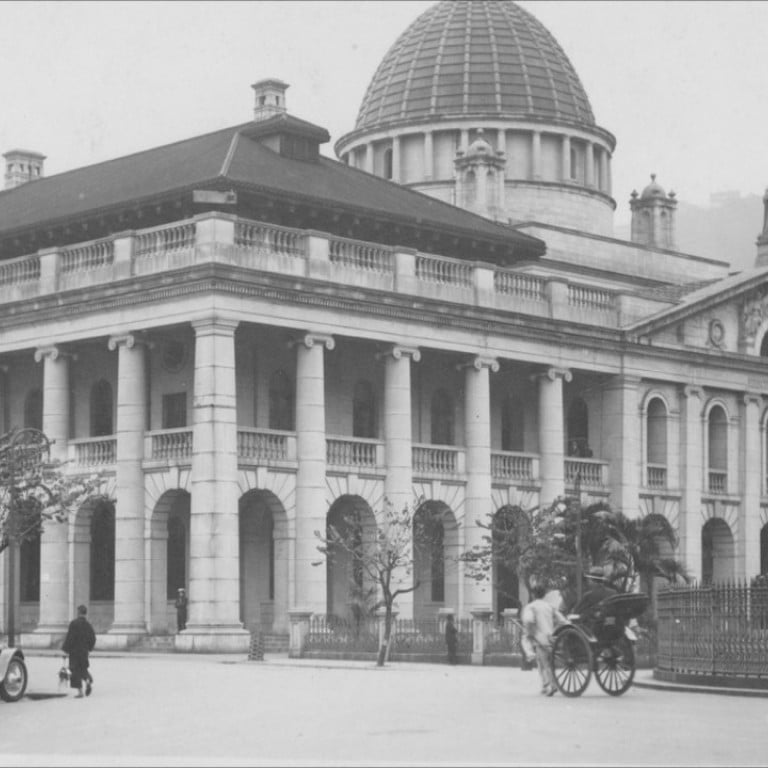

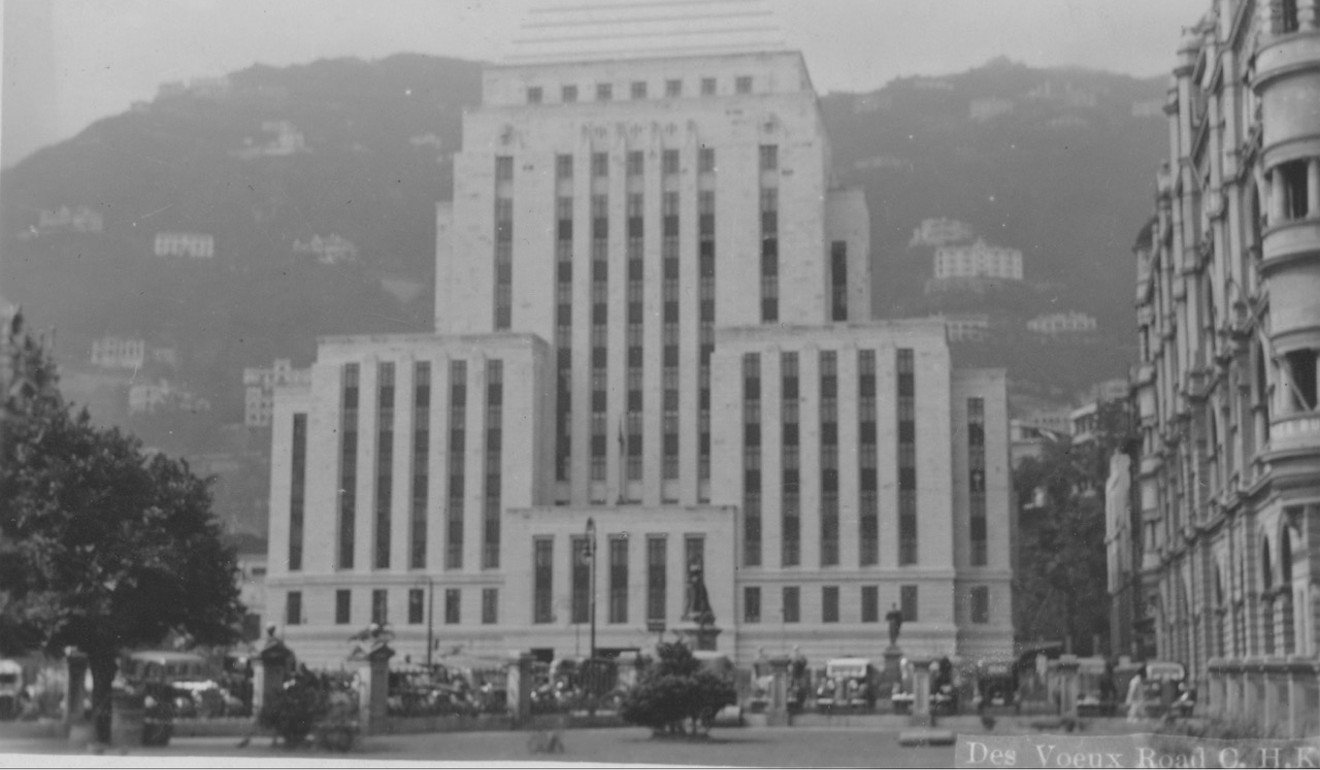

The iron gate leading into the compound was locked behind them as the Japanese headed for the hospital. They were looking for the billet in which the doctor, his wife, Hilda, and their young daughter were living, and their noisy search must have added to the general terror. When the Kempeitai found the room they were looking for, they told Selwyn-Clarke to get dressed. He was to go with them to their headquarters, in Central, in what had once been the Supreme Court Building.

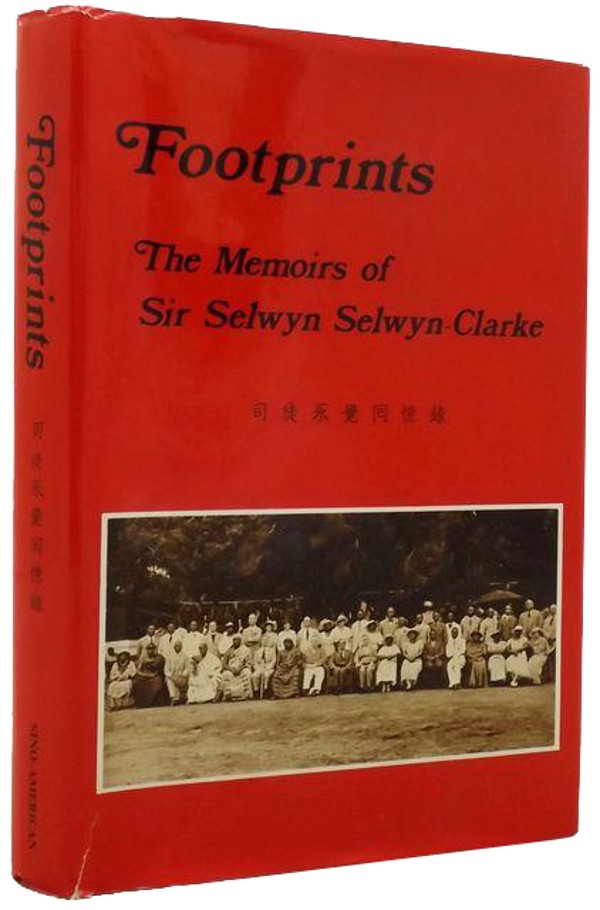

“Not even the strongest can be sure that the methods of investigation employed by people of this kind will not break him,” he wrote in his autobiography, Footprints: The Memoirs of Sir Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke (1975).

His assistant, former Medical Department accountant Frank Angus, and the other doctors were forced to sit in the corridor while the Kempeitai searched their rooms. They were looking for radio sets, large sums of money – anything that would prove the hospital was the centre of a British spy ring. It didn’t take long to find the banknotes that Selwyn-Clarke had secreted around his room, and there was a radio hidden nearby, possession of which meant torture and possible death. Would the searchers find that, too?

My father was the Lane Crawford bakery manager and had been in charge of Hong Kong’s bread production during the bitter fighting that ended in surrender on Christmas Day 1941. Six weeks later, he became part of Selwyn-Clarke’s team at St Paul’s.

He and three colleagues lived in a room in the hospital compound and went out to Wan Chai to bake bread for the sick and needy. By that time he had already met my mother, Evelina Marques d’Oliveira, a Macanese Eurasian with the passport of a Portuguese neutral.

They were introduced by a mutual friend who brought her to the bakery in the hope of a loaf. In the desperate conditions of wartime, things moved quickly and they married at St Joseph’s Church, in Garden Road, on June 29, 1942, with Captain Tanaka, a Japanese officer who had befriended the bakers, in attendance.

There were just over a dozen members of Selwyn-Clarke’s public health squad, some of whom slept in billets away from the hospital. But the largest group of “Stanley stay-outs” was a team of about 40 British, Dutch and Belgian bankers, kept un-interned, along with their families, to operate a skeleton financial service while helping the Japanese to liquidate their banks.

They lived in the cramped and squalid surroundings of the Sun Wah Hotel, close to the waterfront on Connaught Road. Their leader was Vandeleur Grayburn, chief manager of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, the man regarded by some as the real ruler of pre-war Hong Kong: “the Governor’s governor”.

All in all, about 100 adult enemy civilians were allowed to remain un-interned, for the most part because the Japanese needed their services. About the same number were released from Stanley after Chinese or neutral friends promised to be responsible for their livelihoods, while about 20 sick and elderly were allowed to stay full-time in St Paul’s Hospital.

In addition, there were 60 or so Norwegians – interned in February 1943 after two of them escaped – and a small number of Dutch, Belgians and other nationals. All of these “stay-outs” – doctors, bakers, health workers, bankers, missionaries and engineers – experienced the war in a different way to their counterparts on the Stanley peninsula and their relative freedom enabled them to play an important role in the history of the occupation.

The more I learned about my parents’ experiences before their internment, the more I became intrigued by the question: was life for Western Allied civilians better inside or outside Stanley? It was certainly bad enough in the camp, but I think that long before they heard the Japanese marines storming the hospital compound on that terrible morning in May 1943, my parents knew the answer to that question.

At first most of those who managed to avoid internment could hardly believe their luck. Conversation in the St Paul’s canteen – where doctors and bakers ate together before going to a nearby room to enjoy entertainment put on by neutrals – centred on when it would all come to an end and they would be packed off to Stanley.

But as the occupation wore on, the reality of their position became increasingly evident. It was true that, on the whole, rations were slightly higher and those with money could buy extra food in the markets – but in almost every other way life was better behind barbed wire.

American writer Emily Hahn, in her memoir China to Me (1944), describes the even worse ordeal of running into a policeman when the Japanese had decided to “lock down” an area for an important visitor or a security search.

We witnessed daily ... Chinese men, women and children lying on the pavement or huddled in doorways dying gradually of starvation, and looking at passers-by, who were powerless to assist, out of eyes from which all expression had already gone

“There you stand, unless he tells you to move again. Or perhaps […] you don’t stand: you squat. Or maybe you have to kneel. At any rate, you stay where you are told to stay, in whatever position you are ordered to hold, until the order goes around to release you. Sometimes this state of affairs lasts for two hours, sometimes for eight.”

But the unpleasantness they themselves experienced was not the worst thing for the “stay-outs”. They were shocked to the core by the suffering of the Chinese they witnessed almost every time they left their billets.

One of the bankers, Gerald Andrew Leiper, found the sight of this harder to stomach than witnessing the violent punishment the Kempeitai meted out for minor offences.

In his 1982 memoir, A Yen for My Thoughts, he wrote: “Even more distressing than these scenes of brutality was the unforgettable sight, which we witnessed daily, of Chinese men, women and children lying on the pavement or huddled in doorways dying gradually of starvation, and looking at passers-by, who were powerless to assist, out of eyes from which all expression had already gone.”

There is no reason to doubt reports in the Japanese-produced Hongkong News that the governor, Rensuke Isogai, made donations to Chinese charities. But a more common attitude was indifference. Or worse.

Engineer Arthur May acted as a driver for Selwyn-Clarke and he had ample opportunity to witness the brutality with which the desperate were treated. On one occasion he saw a haggard woman in her 70s beaten to death for wailing at a sentry who was burning the leaves she had collected to exchange for a bowl of rice.

More than 40 years later, May wrote to University of Hong Kong historian Christine Henderson that he was still moved to “speechless tearful sorrow” when he recalled such atrocities.

But the violence dispensed by individual soldiers was not nearly as bad as the organised brutality of the Kempeitai.

From the beginning, the Japanese had tried to reduce Hong Kong’s swollen numbers to a more manageable size. In early 1943, the Kempeitai started rounding up people in the streets, often refugees and other impoverished residents, but sometimes those with secure livelihoods.

If they were lucky, these deportees were dumped close to the border, but some were put on junks that were then floated out into the harbour and burnt, or sunk for artillery practice.

Health inspector Edward Kerrison was forced to take charge of recovering and cremating bodies from the boats, which went out every afternoon. Some were killed even before they set sail: he watched in horror while people were lined up along the wharf and machine-gunned into the water.

I could hear the fury in my father’s voice when, more than 30 years later, he told me about these callous murders. He and my mother had decided to speak as little as possible about their wartime experiences in order to avoid distressing my brother and me, but some things just seemed to force their way out.

The Chinese were not just helpless victims of Japanese brutality: they fought back and enabled some of the British contingent to do the same. Communist-leaning guerillas existed in Kowloon and the New Territories even before the Japanese attack, and as the occupation continued they became an effective resistance force, now generally known as the East River Column.

On January 9, 1942, Lindsay Ride – a professor of physiology at the University of Hong Kong – was sprung from Sham Shui Po POW camp by one of his assistants, Francis Lee Yiu-piu.

The guerillas helped them on their way, and on the long, difficult journey Ride and Lee made plans that would result in the formation of a resistance organisation based in Free China – the British Army Aid Group (BAAG). In June 1942, the first agents arrived in Hong Kong, and the “stay-outs” were high on their contact list.

The medical workers at St Paul’s were rather a disappointment. One doctor, who had been a friend of Ride’s before the war, was pressed to escape but declined. Although Selwyn-Clarke provided the BAAG with a little information, he was worried about cooperating with a military organisation because he believed his Hippocratic Oath and his promises to the Japanese both demanded he confine himself to humanitarian work.

The BAAG had more luck at the Sun Wah Hotel. In November, they whisked two bankers out of Hong Kong to pass on valuable financial information to the British authorities. In spite of his age – he was 60 when the Japanese attacked – and indifferent health, Grayburn became an agent, code name “Night”, as did his Hongkong and Shanghai Bank No 2, David Edmondston. Charles Hyde, from the bank’s Kowloon branch, worked with two other “stay-outs” and a prominent Portuguese lawyer to organise escapes and send a stream of valuable information to the BAAG.

Selwyn-Clarke’s team of humanitarians also had to depend on the Chinese and so-called third nationals who provided most of the funding for the relief operation. At first, Selwyn-Clarke financed his work with loans or gifts from wealthy Indian and Chinese sympathisers. When this no longer addressed the scale of the need, he called on the bankers to help. Grayburn’s team raised loans totalling more than HK$900,000 – worth about HK$40 million today.

It is striking that the bankers’ Japanese supervisors knew what they were doing and made no attempt to stop them. But the bankers were warned that if the Kempeitai found out what was going on, they were on their own – like most Japanese civilians, the supervisors were themselves terrified of the gendarmes.

It is no doubt true that in town, as in Stanley, the ideas of the time confined most female Allied civilians to domestic and support roles. But in both locations a few brave women decided that new circumstances called for new attitudes.

Prominent among them was Ellen Lee, who had remained un-interned on a spurious claim of being Irish and was tireless in defying, harassing and deceiving the Japanese authorities in the interests of getting supplies into Sham Shui Po. This campaign cost her a bullet in the leg, but nevertheless Lee was one of those who moved from relief to resistance.

Before the war she had held conventional views about “a woman’s place” but – rather to her surprise – she found herself cooperating with the guerillas in the highly dangerous business of helping four British soldiers escape into China. It’s no surprise that Lee’s 1960 memoir, Twilight in Hong Kong, written under her maiden name, Ellen Field, makes exciting reading.

Kiyoshi Watanabe – a Japanese interpreter who risked his life on innumerable occasions to help the humanitarian effort – warned Lee that she was about to be arrested, and she managed to escape to Macau with her three daughters. Others were not so lucky.

By the time the gendarmes arrived at St Paul’s Hospital, Grayburn and a fellow banker were in prison facing charges of smuggling money into Stanley, and Hyde had been caught communicating with the Indian POWs. Selwyn-Clarke wasn’t the only one taken on May 2, 1943, either. He was accompanied to the cells by health inspector Alexander Sinton and hundreds of others were arrested in the weeks that followed.

Nevertheless, Selwyn-Clarke’s careful preparations and quick thinking on the morning of his arrest prevented an even worse disaster. When he realised the Japanese were in the hospital, he alerted his assistant, Angus, one of whose jobs was to keep track of the finances.

Angus immediately destroyed the records that related to Stanley, Sham Shui Po and the other camps, entrusting the rest to Dr Lai Po-chuen, who had already agreed to continue the illegal relief operation. The radio turned out to be so well hidden that it eluded the searchers and, when the doctors got back to their rooms, they found that Selwyn-Clarke had managed to fool the Kempeitai.

George Graham-Cumming, a courageous doctor who played a role in both humanitarian relief and military resistance, tells us what happened, in an unpublished memoir, the only detailed eyewitness account of these dramatic events.

“Selwyn had currency hidden all over the place. Some he had laid out in obvious places as a kind of blind and it had worked. The searchers, finding this not inconsiderable sum, had concluded as intended that it was all there was. It seemed enough!”

Graham-Cumming watched “astounded” as Angus removed the really large sums from their “incredible” hiding places. Even though the Japanese were close by, the doctors managed to get the cash to Eurasian members of staff, to be passed on to Dr Lai.

While all this was happening, Selwyn-Clarke – stripped of everything but his shirt and trousers – was confined in a tiny windowless cell containing nothing but a bucket and a mug for water. At nights he slept on the concrete floor, crawled over by cockroaches from a nearby latrine.

From these foul conditions, the bookish medical administrator, 50 years old and already frail from the rigours of the occupation, conducted a campaign of resistance that is, in its own way, one of the epics of the Hong Kong war.

Ten months of torture, which continued even after he was sentenced to death, failed to break him, and he refused to incriminate himself or a single one of those who had helped him in his clandestine operation.

His courage saved many lives, and eventually his own, as the Japanese, always reluctant to execute Europeans without a confession, commuted his death sentence and sent him to Stanley Prison.

Most of the “stay-outs” were driven down to the Stanley camp in the three months that followed Selwyn-Clarke’s arrest. Leiper records the relief he felt at being with his own community and the pleasure of being in attractive surroundings and breathing fresh air – in his view all of this outweighed the slightly smaller rations provided in camp.

Even in the relative tranquillity of Stanley, though, the new internees could not escape the consequences of their time in town.

If there was one day in my father’s life worse than that of Selwyn-Clarke’s arrest, it was October 29, 1943, when he was with Hyde’s wife, Florence, while her husband was executed on Stanley Beach. Sinton and two fellow “stay-outs” also died that day, alongside 29 other BAAG agents. They weren’t the only casualties.

Grayburn managed to keep from his interrogators his role as a BAAG agent, but died of malnutrition and medical neglect in August 1943, while serving a three-month sentence for money smuggling. Edmondston passed in much the same way about a year later.

The statistics speak for themselves: although those interned from the start were about 20 times more numerous than the “stay-outs”, about the same number of each group were executed or died in prison.

Much to his own surprise, Selwyn-Clarke managed to avoid being among their number.

He was sent from Stanley Prison to the recently opened Ma Tau Wai camp in December 1944 as part of an amnesty to mark the anniversary of the outbreak of the Pacific war. It was an astonishing and unexpected turnaround in his fortunes: “The sense of relief was almost too much for me. I felt completely dazed,” he wrote in his autobiography.

He had been close to death, but now he was to become the medical officer of a relatively relaxed internment camp, with Hilda and their daughter transferred from Stanley to be with him. One of those he found there was Edward “Pop” Gingle, the colourful restaurateur who was to become probably the best-known American in post-war Hong Kong.

There were now only a handful of “stay-outs” left to endure the last year of the occupation. One was Mildred Dibden, a missionary who had worked heroically to care for the orphans in Fanling Babies Home: at one point she was making monthly walks of 30km each way to secure food supplies.

Dibden and her helpers eked out a living by becoming pig breeders and cobblers, barely managing to keep going as supplies dwindled. The end of the war came just in time. According to some estimates, there was no more than a month’s supply of provisions remaining in Hong Kong at the time of the Japanese surrender.

The Japanese occupation was hard for everyone; whatever their ethnicity or pre-war status, all Hong Kong’s people faced continual anxiety and hunger. But the contradictory nature of Japanese racism meant that those from Western Allied nations suffered far less than the Chinese and other Asians who, the conquerors claimed, were under Japanese protection in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Of the Western Allied civilians, those I’ve been calling the “Stanley stay-outs” suffered the most. They might have had slightly fuller stomachs than their compatriots in the camp, but they paid for this with isolation and anxiety. Greater ability to act meant more liability to punishment, and walking through streets that had been familiar in peacetime forced them to confront in a much more intense way the horrors inflicted on Hong Kong’s Chinese residents.

Life in Stanley was appalling, but in one of the grim paradoxes of war, the barbed wire that surrounded the internment camp proved a protection as well as a barrier.