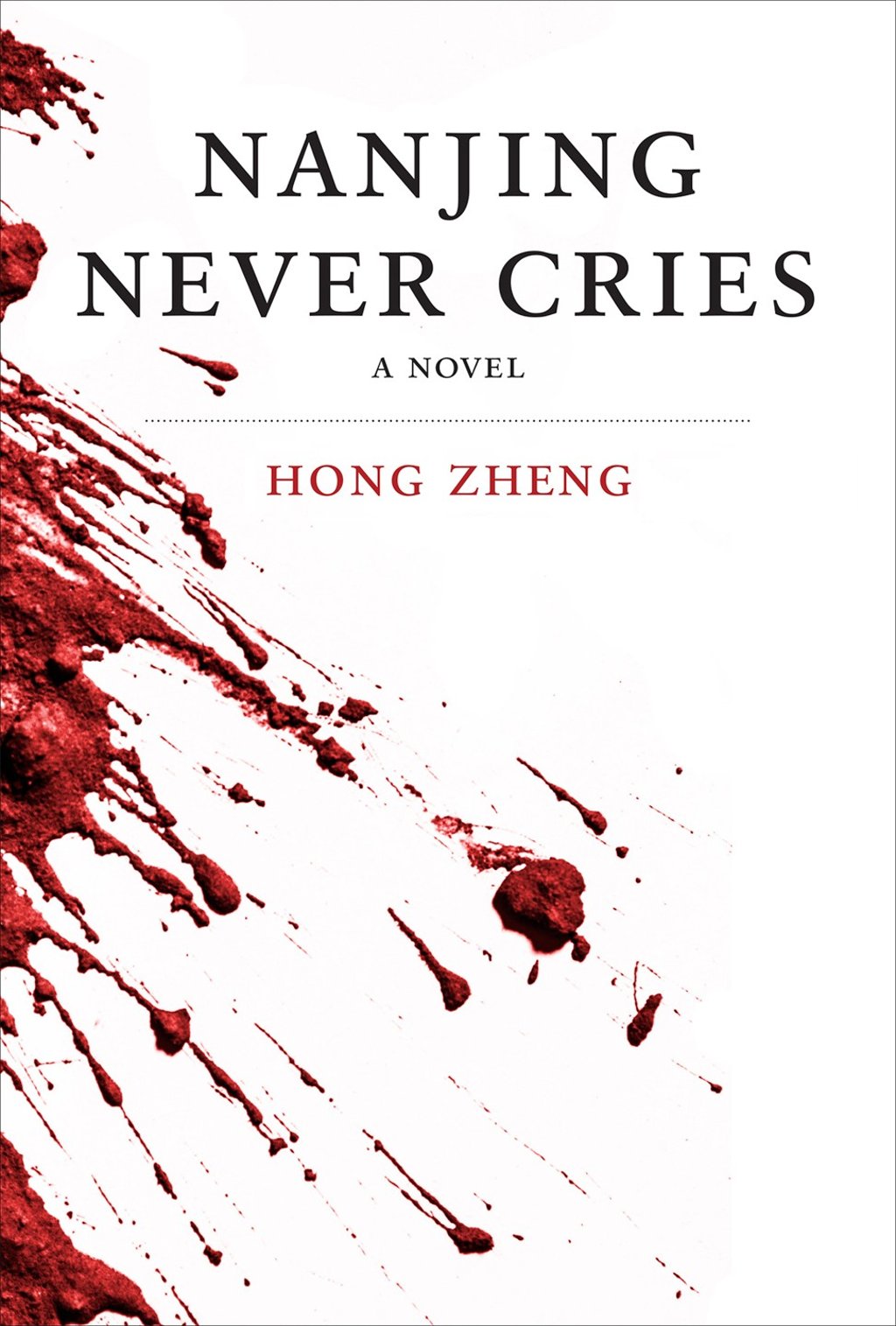

‘Americans not the bad guys’ – Nanjing Never Cries author sets the record straight

MIT scholar Hung Cheng, also known as Hong Zheng, felt obliged to write about the 1937 massacre of Chinese civilians by Japanese troops after American historians left him reeling from their misguided views

It is 80 years since the Japanese army invaded Nanking, a city today known as Nanjing. What happened over the next six weeks has become known around the world as the Nanking massacre. About 50,000 Japanese soldiers killed, raped and looted indiscriminately. Estimates of the dead are as high as 300,000. The atrocity was described in several eyewitness accounts, including diaries by Westerners John Rabe and Minnie Vautrin, and film taken by John Magee.

When I ask Cheng about the origins of the book, he suggests another date: April 13, 1995. This was when he gatecrashed a symposium hosted by MIT entitled “The Atomic Bombs: Myth, Memory and History”. Three of the speakers were American (professors Philip Morrison, John W. Dower and Charles Weiner); the other was Rinjiro Sodei, a professor at Tokyo’s Hosei University.

As Cheng recalls in the preface to Nanjing Never Cries, he was urged to attend by two colleagues who informed him that “historians are distorting history!”

“The speakers were presenting their view of the [second world] war in a way I had never heard of,” says Cheng, 80. “I heard this story that the Americans were the bad guys for dropping the bomb. So I had to tell them how I felt about that. I cannot let my students, who are quite impressionable, hear only one side. I have to let them know how many people like us are feeling about the Sino-Japanese war.”

The question Cheng asked that day was provocative to say the least: “If a group of bandits broke into your home, raped your wife, killed your children, and were about to slit your throat before being subdued by the police, would the story be police brutality to you?