Hong Kong crime files: the siege of Gresson Street 100 years ago, and why it was forgotten for so long

Little was remembered of the bloody gunfight in Wan Chai in January 1918 that left five policemen and a young boy dead, until a London-Irish descendant of one of those killed stumbled upon the story

This innocuous street that connects Johnston Road with Queen’s Road East seems an unlikely location for what the main headline in a late edition of the China Mail on January 22, 1918, called a “sensational affair in Hong Kong”. These days, Gresson Street is home to a few modest restaurants, a residential block and the stalls of hawkers selling orchids and exotic fruit in the prelude to Lunar New Year.

“I have worked here for 30 years and I have never heard of that,” says Juliana, a passion-fruit vendor (who prefers not to give her full name), when told that 100 years ago tomorrow, this was the scene of a bloody siege and shoot-out. An old man smoking a cigarette outside the Xing Bin dim sum restaurant shakes his head blankly when asked about the so-called Gresson Street siege.

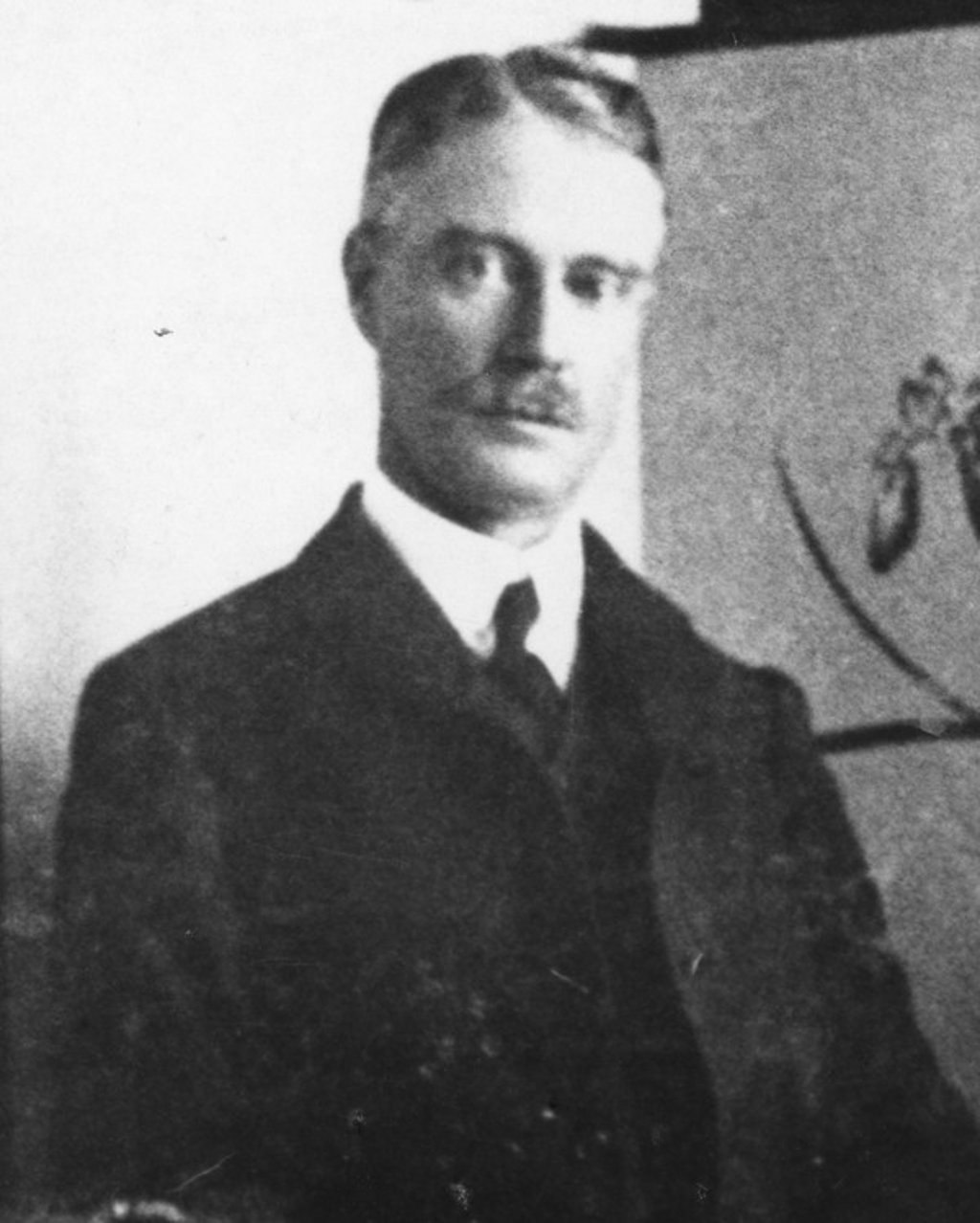

“Mortimor O’Sullivan died here; that’s why I first came to Hong Kong,” says music teacher-turned-historical author Patricia O’Sullivan, sheltering from the cold rain under the awning of the restaurant at 6 Gresson Street. Her great-uncle “Murt”, an inspector in the Hong Kong Police Force, was shot dead on the first floor of the building that stood where she does now.

Live the history of Hong Kong, how it grew from colonial opium trading outpost to global finance mecca

The London-Irish woman knew nothing about her great-uncle’s death until the elderly parents she had been caring for in Hertfordshire, England, both died in 2006. To take her mind off feeling gloomy, the following January, she took a trip to the ancestral village of Newmarket, in the rural southwest of Ireland, and started digging into the family tree.