The little-known Scottish author taking China by storm with her Ferryman novels

The biggest English-language novelist in China right now is a woman who lives in Scotland and writes books aimed at young adults. But it’s not J.K. Rowling. Who is Claire McFall?

If you have not been paying attention to China’s bestseller lists, you would be forgiven for not being familiar with Claire McFall’s name. If you had, you would know two McFall novels are placed squarely in the Top 10. One, Ferryman (2013), has been a near-permanent fixture for more than two years. That’s right: two years, selling more than a million copies in the process. That’s right: one million copies. Ferryman has received more than 500,000 reviews on Chinese electronic-commerce platform Dangdang alone.

McFall’s debut has now been joined in the Top 10 by a sequel, Trespassers (2017), which has proved a more immediate hit than its predecessor. Both books narrate the strange adventures of a Scottish teenager, Dylan, and her otherworldly other half, Tristan. Part two expands this romance to include Tristan’s unrequited lover, Susanna, and Jack, a surly young tearaway.

And just when it seemed that McFall’s star couldn’t rise much higher, in China at least, news has just been announced of a film deal with American media company Legendary Entertainment, which has produced blockbusters such as Batman Begins (2005) and Inception (2010) and is a subsidiary of Chinese conglomerate Dalian Wanda.

What makes McFall’s story more intriguing than the usual rags-to-riches tale is the contrast between the writer’s vast success everywhere from Hong Kong to Shanghai and her near-anonymity in her homeland. Ferryman may have been nominated for several awards in Scotland, but its author is far from being a household name.

That McFall greets these trials with a measure of good grace might have something to do with her day job teaching English, which she still does part time. Indeed, she sounds angrier on the school’s behalf than at them. “Schools are struggling just now because no one has got any money. The Scottish Book Trust has a Live Literature fund, which pays half the author’s fees and expenses. That is the only way most schools can get authors in.”

Being an English teacher, there seems to be a divide between literary novels that you can study and the novels kids read for fun. I would quite like to be the novel they read for fun. That’s why I like books

Now compare that reception with McFall’s first visit to Beijing early last year, where she was greeted like a mega-star. “It was great. It was kind of crazy in that lots of people seemed to know my name,” she says. “I was chauffeured around the place and people were very pleased to see me.”

Her first real taste of celebrity occurred during a visit to the National Library of China. “They had this booth that looked like a Dr Who Tardis. The idea was you would read a piece of your favourite literature and they would record it and keep it as a literature memory.” McFall was approached by a camera crew who thought she was just another Western visitor. One mention of her name, however, led to immediate recognition and excitement. “It was mad for me, because if you said my name in the middle of Glasgow, they would say, ‘Who?’ It was a recognisable name in Beijing.”

McFall recounts her giddy excitement rapidly, her thoughts spilling into one another. This enthusiasm seems to be her default setting. She chats breezily about everything from ice hockey to her young son, Harry.

It turns out McFall writes like she talks: “really, really fast”. “I can write a story almost as fast as I can read one. Actually, I don’t feel like I am writing. I feel like I am in a story in my head.” And in sharp contrast to the advice she gives to her students, she hates planning. “If you plan every single thing, what is the point in writing the book? There is nothing new to discover. I have a concept and an end point I am aiming for. Then I just see how it gets there.”

Such headlong creative excitement can lead her down blind alleys. She mentions “four or five manuscripts” that ran out of steam at 30,000 words. “You think, ‘This is rubbish.’ Usually because I have lost the feeling or an atmosphere. If I lose that I give up.”

Atmosphere was vital in inspiring Ferryman, which began literally in the middle of nowhere. “I had a really long commute between Innerleithen, where I was living, and Lesmahagow, where I was teaching. It’s a whole big world of nothing. Everyone always says the Scottish countryside is so beautiful, and yeah, it is. But for most of the year, it’s pretty bleak. The atmosphere came from the landscape in autumn. It was cold, windy, snow and it was raining. It was empty-heather or hills for miles and miles. I don’t want to say despair. Emptiness? But that was the setting for Ferryman.”

[Ferryman] started from very humble beginnings. I was delighted to see it in print, then I was even more delighted by its recognition in Scotland. Its success in China has been incredible, and allowed me to share the story with a wide and varied audience

McFall began to populate this wasteland with her outsider heroine, Dylan. “Within that [setting] was an awkward teenage girl that every woman still is. The character and the setting melded together.” Dylan enters this barren highland from a long, dark tunnel: she has just survived a train crash, or so she thinks. She sees countryside that “was untamed and unfriendly looking”, which pretty much describes Tristan, the handsome, sandy-haired teenager who curiously seems to be waiting for her: “His face was set in a hard, disinterested mask, and as soon as Dylan got closer to him, he’d begun to stare off into the desolate landscape.”

Two key facts are missing from this passage: Dylan has just died in the train wreck; and Tristan is the titular Ferryman, a supernatural version of Greek mythology’s Charon, who transports lost souls through purgatory towards salvation. This being young adult fiction, McFall’s purgatory feels like The Hunger Games: blocking Dylan and Tristan’s path are vicious wraiths who “try to snatch souls during the crossing”.

Without wishing to spoil either book, Dylan and Tristan fall passionately in love, which drives them to make life-changing – or is that death-changing – choices. Ferryman’s brand of post-apocalyptic spiritual horror contrasts with Trespassers, which returns the couple to an all-too realistic contemporary Scotland. Tristan displaces Dylan as the fish out of water, navigating not dystopian wilderness but supermarkets, schools, suspicious mothers and, in one nicely observed scene, neckties. The horror quickly returns, however, when Tristan and Dylan are joined by more beings from the other side: Susanna, Jack the dead rebel and a flock of wraiths.

Given that both novels evoke the skin-crawling horrors of school (bullies, girls desperate to steal your supernaturally handsome boyfriend), I begin by asking the obvious question: does 35-year-old McFall have much in common with Dylan, her awkward teenage creation?

“Absolutely,” she says. “She’s as hopeless as I was. I was lead trumpet in band as well. I just wasn’t cool.”

McFall’s early years were spent in England. Although her parents are both from Glasgow, McFall was born in Peterborough, and lived there until her 10th birthday, when the family moved to South Lanarkshire, “a cluster of villages about an hour south of Glasgow”. The community was tight-knit, the area “quite deprived. There are worse places. A lot of the industry like mining has gone”.

[Dylan is] as hopeless as I was. I was lead trumpet in band as well. I just wasn’t cool

McFall suffered her share of culture shock. “I was the English person in the slightly rough Scottish school. Not good.” Like Dylan, she was also shy, cosseted and clever in an environment that didn’t prize any of these traits. “All the girls wore perfume and make-up. Even though they lived in the countryside, they grew up a little faster. I got myself a Scottish accent and learned to swear quite quickly. That was my coping mechanism.”

This jarring experience was softened a little by books: McFall’s formative favourites included boarding-school classic Malory Towers, crime novels by Sue Grafton and Karin Slaughter, and the Point series of horror and romance novels. “I just like being in other worlds and trying on someone else’s life,” McFall says. “You read and get to have a go at being another character for a wee while. If you read books you get to live a thousand lives.”

It didn’t take her long to try her hand at writing too. “I had a typewriter when I was in school. This, again, is how uncool I was. I used to bash out on blue tracing paper. I would get to 20 or 30 pages and run out of ideas. I didn’t have a concept of what a novel was at that point; the overarching narrative and pacing it takes to create a novel; how little scenes build up into a bigger storyline.”

Ferryman was McFall’s first completed novel. Finished in 2011, the early drafts were “pretty awful. I was very proud of finishing the book, but it was not great, to be honest”. All these early versions had the basic blueprint: bleak landscape, McFall’s teenage heroine and the figure of “Death”, glimpsed everywhere from Greek mythology to Chinese culture. “Quite often he is hooded and you don’t even see his face. I just wanted to give him a more human face. If this was your fate, what would it be like?”

I can write a story almost as fast as I can read one. Actually, I don’t feel like I am writing. I feel like I am in a story in my head

Is she the sort of person who obsesses about death? “You wouldn’t think it to read my books, but I am quite cheery and cheerful. I don’t know what happened!” Nor is McFall religious, a fact that made her uncertain of how to end the story. Ferryman’s original draft left Tristan and Dylan stranded and separated at the gates of heaven.

“I was nervous of stepping on religion’s toes, but I didn’t want it to be a religious book. How can I write an afterlife that doesn’t tap into any of the religious ideas that we have?” Shining light onto these dark themes is Ferryman’s love story. One glance at the internet comments about both books shows that Dylan and Tristan have ignited readers’ imaginations around the world. If McFall isn’t death-obsessed, is she a romantic?

“I must be,” she responds, a little uncertainly. “I wouldn’t have thought so, but deep, deep down,” McFall giggles. “Everybody loves romance. The whole point of being here is to make connections, and the main connection everyone is looking for is the romantic one.” Ferryman, she argues, is like a primer for serious adult relationships. “When you are a teenager, you are just taking your baby steps into [romance]. When you read fiction, you can practise by experiencing the real emotions of others. It’s like people having crushes on boy bands – it’s safe.”

I just like being in other worlds and trying on someone else’s life,” McFall says. “You read and get to have a go at being another character for a wee while. If you read books you get to live a thousand lives

Ferryman’s path to success sounds as complicated as Dylan and Tristan’s story. After a bad experience with one literary agent (“a bit of a charlatan”), she found Ben Ellis, who selected Ferryman from a pile of McFall’s completed manuscripts. “‘It was a sweet little story’ – those were his exact words,” McFall says. “I was quite surprised. It was the first thing I had written and I thought I had got better since then. But he saw potential in it. We call it, The Little Book That Could.”

The novel was picked up by Templar Publishing and gained further exposure when it was selected by schoolchildren across Scotland for the Scottish Children’s Book Awards. “What I liked about that was it was kids who read it,” she says. “Being an English teacher, there seems to be a divide between literary novels that you can study and the novels kids read for fun. I would quite like to be the novel they read for fun. That’s why I like books.”

Then, one afternoon in October 2015, McFall was idly googling her name when she chanced upon Dangdang. She was gobsmacked. “Ferryman had got 46,000 reviews. How can it have 46,000 reviews? It was No 10 on Amazon China. I thought, ‘It’s selling quite well.’”

McFall and her agent investigated. “We discovered the Open Book chart, and Ferryman was in the Top 10. And it stayed in the Top 10 and it stayed in the Top 10. It’s still there. This is the 25th month. It is bananas! I don’t quite understand it. I am delighted.”

White Horse Times did not contact McFall about Ferryman’s enormous success. She couldn’t read the translation, so couldn’t judge how faithfully it had been executed – “What people have said to me about things they liked has chimed with the story I know” – but McFall educated herself quickly about publishing in China. For one thing, Ferryman was not marketed as young adult fiction, which may explain why some adult readers noted a certain childishness in the prose. “I quite agree with that. When I wrote it, I thought of a teenage audience.”

But the question remains: how did a novel by an obscure Scottish writer about a Scottish teenager and a supernatural being impersonating a Scottish teenager become a blockbuster in China? “I am not really sure,” McFall says, smiling. “A lot of things that have come back [from China] are similar to what kids in the UK have said. They really like the love story. They really fall in love with the main character of Tristan. I wrote him as the boy the teenage me would have been intimidated by but would have wanted to get closer to. Me being me and geeky, I would never have dared. I would have run away and hid.”

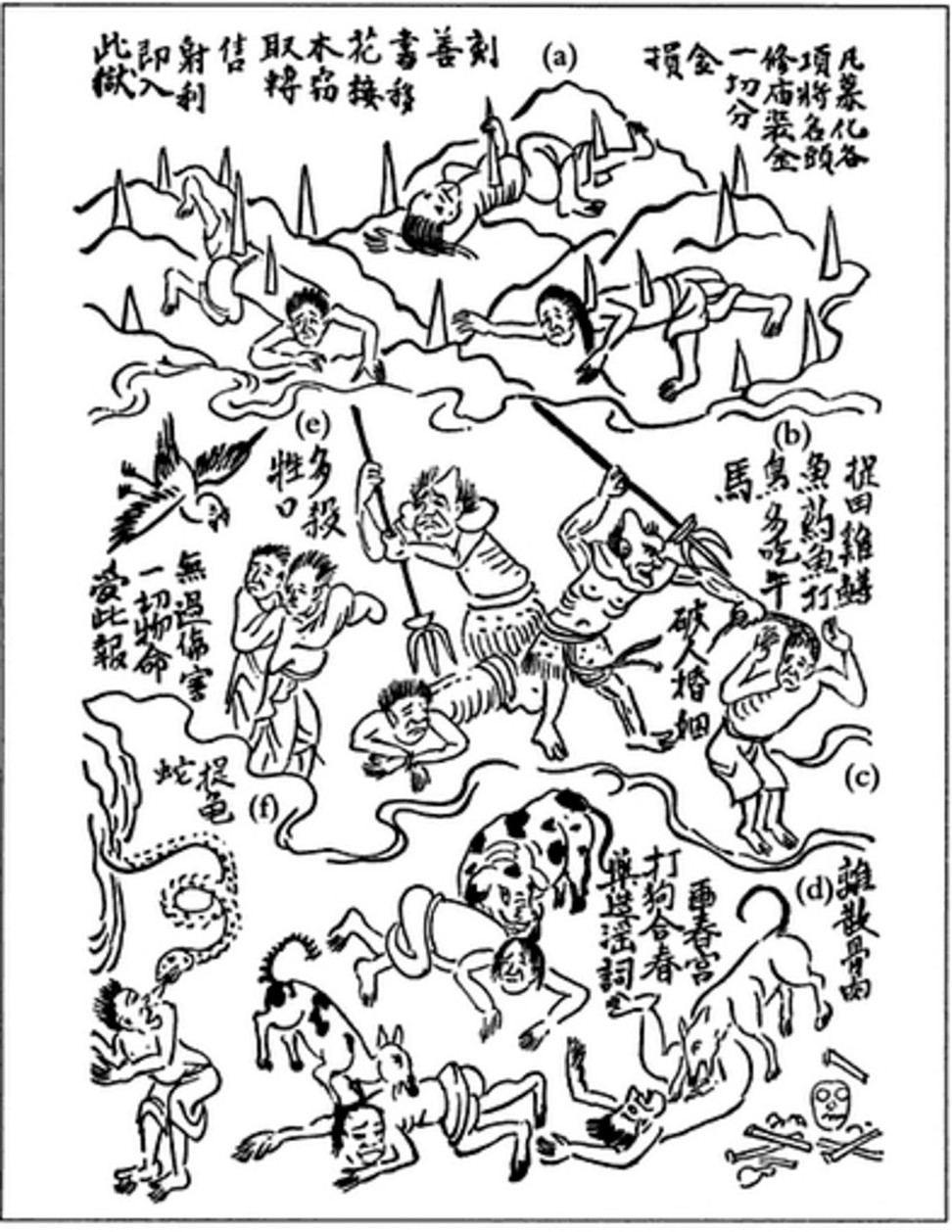

McFall also proposes some similarity between her portrait of the ‘Ferryman’ and the heibai wuchang, the “black and white impermanence” deities who, like Charon and Tristan, guide the dead to the afterlife. “But they are quite terrifying. I think readers like the idea of the fantasy journey.”

A lot of readers she met in Beijing asked about the finer points of Scottish culture, like Hogmanay, the New Year’s celebration. Did Scotland need much translation for Chinese fans? “A lot of readers weren’t even aware that I am from Scotland. They just think it’s Britain.”

Did anyone mention that Dylan is an only child making her way in a tough world, something that might resonate with the one-child policy? “It is very possible. No one has said that to me. But you relate to things in different ways depending on your circumstances.”

To say Ferryman has changed McFall’s life is an understatement. While she and her archaeologist husband made decent money, they struggled like many others to maintain a certain standard of living. Ferryman’s sales in China allowed them to buy a new house and enabled McFall to teach part-time. “After I had my son that was really important. I didn’t want to be teaching all the time. Because I write in the evening, when he is asleep, when I am not teaching I can be with him.”

A potentially more challenging consequence of the success is that McFall is no longer writing into a vacuum. The level of anticipation for Trespassers in China was signalled by the fact that the Chinese translation was published almost two weeks before the English original. Did McFall have any hesitation about writing a sequel? She has published two stand-alone novels – Bomb Maker (2014) and Black Cairn Point (2015), the latter having also been translated into Chinese – in between the two Ferryman instalments.

McFall’s Chinese readership has affected her creative process. One of the souls guided by Susanna, the “Ferrywoman” in Trespassers, is You Yu, an elderly woman who dies contentedly in her village in China. She was, McFall says, named after the grandmother of the rights director at White Horse Times, and was intended as a contrast to the unhappy and desperate souls the writer had depicted before. “A lot of the souls in Ferryman have wasted their lives. I wanted to write about someone whose life was well-lived and who was happy with their time and ready to move on. I wanted someone who was wise and comforting.”

The good news for Ferryman addicts is that McFall has already written 30,000 words of part three. “It doesn’t matter to me that it gets published. I want there to be a completeness to the story in my own head,” she says. Anyone quivering with anxiety at these words might be calmed by McFall’s next. “I imagine it will be published.”

In the meantime, there is another, stand-alone novel to complete, the details of which McFall is keeping close to her chest. And, of course, there’s that movie deal. It seems fitting for this most unassuming of blockbusters that McFall was at work teaching when the news came through. “I was speechless. [Ferryman] started from very humble beginnings. I was delighted to see it in print, then I was even more delighted by its recognition in Scotland. Its success in China has been incredible, and allowed me to share the story with a wide and varied audience, something I couldn’t have comprehended writing those first few words back at the very beginning.

“Now, with Legendary buying up the film rights, it’s a new chapter. I can’t wait to see what the journey has in store.”