Hong Kong priest’s mission to save drug mules from a system that favours kingpins

Crusading prison chaplain is seeking shorter jail terms for couriers and greater police efforts to hunt down senior gang members

In the hustle and mayhem of a downtown Bangkok street teeming with prostitutes, sex tourists, garish bars and counterfeit-goods stalls, a grey-haired priest stops beneath a pedestrian footbridge to talk to two cocaine dealers from Ghana.

“It’s 4,000 baht [US$130] a gram,” one of the dealers mumbles, rummaging in his jacket pockets and shuffling nervously from foot to foot. His eyes then land on the crucifix around the man’s neck and he says, with a broad grin, “I’m a Catholic too, Father.”

The priest smiles, leans in and asks the dealer questions in a low voice. He hands the African a booklet explaining his work, tells him, “Look after yourself,” and walks deeper into the city’s dark heart.

Father John Wotherspoon is a man on a mission. He has flown to Thailand from Hong Kong to track down a Nigerian drug kingpin known as IK in a corner of Bangkok so lawless, even local police consider it a no-go zone. Armed with little more than his crucifix and an implacable faith in human nature, the 71-year-old is racing against time to get evidence that might lessen the jail sentence for a mainland Chinese woman called Li Dandan.

“She’s in court this week and I need to find him and get him to confirm to me that she was set up,” he explains, clutching photocopied pictures of IK, who the suspect says seduced her and then conned her into flying from Kuala Lumpur to Hong Kong with a cocaine-filled suitcase.

The hunt leads Wotherspoon to an Ethiopian restaurant in a side street populated by drug dealers in the area where he is told IK’s gang operates. Here, just the mention of the name IK produces looks of alarm as young African men laugh nervously, shake their heads and scatter into alleys and shop doorways, glaring as they tap urgent messages into their phones. It is clearly time for the priest to beat a hasty retreat.

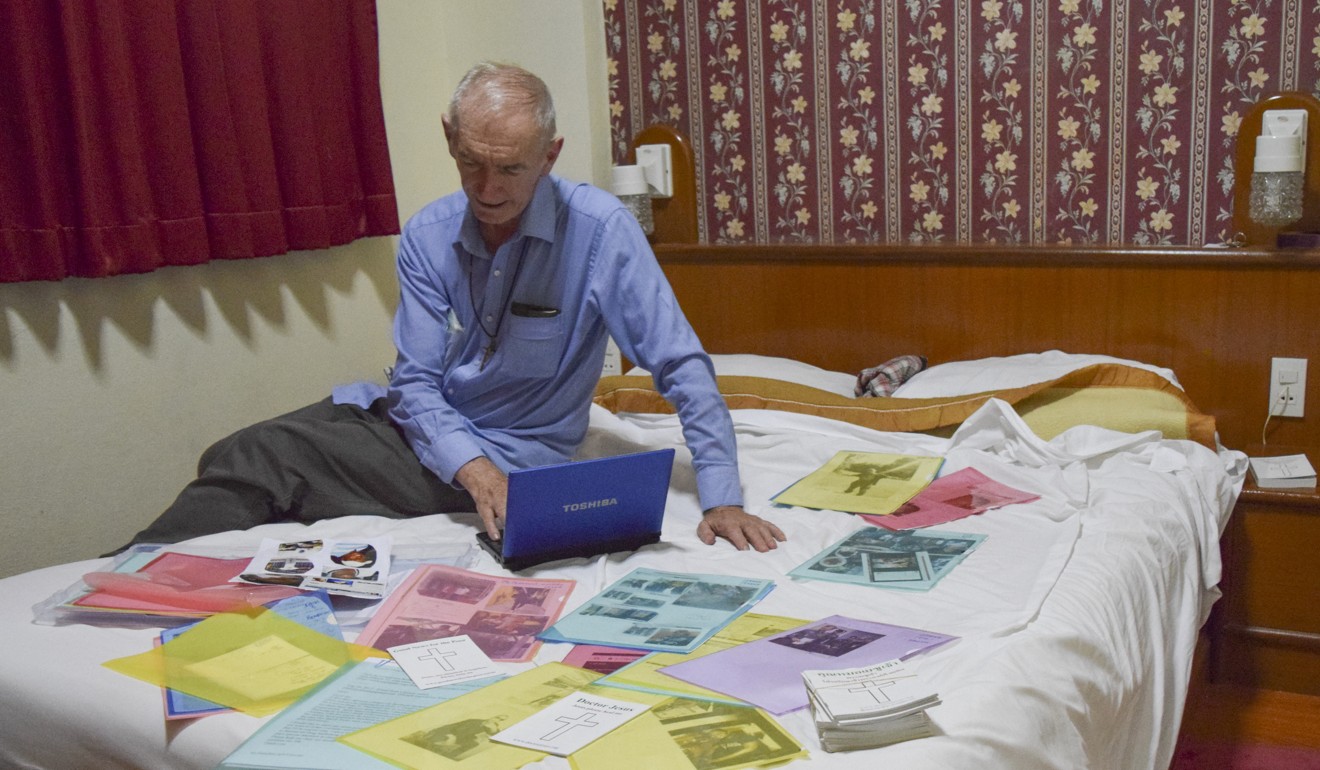

“Of course, I do worry about my safety sometimes,” Wotherspoon confesses later, in his drab HK$200-a-night hotel room, a Bible by his bedside, as he pores over untidy bundles of papers and photographs relating to cases involving the drug mules in Hong Kong he is trying to help. “But when I feel tired or scared or nervous, I think about the women in prison and I keep going for their sake. They are away from their families. They are innocent. The vast majority of them are single mothers trying to look after their children.”

The solo campaign waged by Wotherspoon has also shed an uncomfortable light on Hong Kong’s handling of drug trafficking cases and the way informants are used to identify mules while apparently leaving kingpins and syndicate bosses largely untouched.

No account is taken of the role of the couriers, and how high up or low down they are in the hierarchy

Hong Kong hands out some of the world’s harshest punishments for drug mules, with a sentencing starting point of 22 years for 1kg of a class-A drug and no reduction for being either of previous good character or a mule rather than a gang leader.

Now, however, in a landmark hearing, a panel of appeal court judges is to consider amending sentencing guidelines to give lower jail terms to mules and couriers than to senior gang members. Lawyers for a trafficker sentenced to 13 years and eight months in 2016 for smuggling cocaine are asking the judges to jail traffickers on a “proportionality basis as adopted in England and Australia”, citing Wotherspoon’s campaign as evidence of the need for change.

“Customs have these informers who can’t be arrested and won’t be arrested. [Criminals further up the food chain] sacrifice one person a month. That way, customs get their quota of arrests and the drug lord gets protection, while the poor mule gets 10 years or more in prison.”

Some informers – including a Nigerian living in the New Territories and married to a local woman – remain active in the drugs trade and free to travel overseas to recruit more mules, says Wotherspoon. It is, he says, a policy that encourages rather than diminishes the global drugs trade.

“There should be a judicial inquiry into the whole mess,” he argues. “It is a can of worms. There are a lot of things going on that shouldn’t be going on. After all, this is Hong Kong, not Russia or North Korea.”

Wotherspoon made efforts to liaise with customs officials for the first two years of his campaign but says he now has little contact with them. “I would love to work with customs but it has been so difficult,” he says. “The department is not transparent.”

“Only a very tiny number of female drug mules have made more than one trip,” he says. “They are trying to get money for the good life. The vast majority are just poor and desperately in need of money for themselves and their families. They are single mothers. A number of them have HIV and husbands who have died. In their need for money they come into contact with people looking for people to use. They only stand to make about US$4,000 and they never get paid anything in advance.”

Dealing with the offenders who bring the drugs into Hong Kong is one solitary aspect of the problem and goes nowhere near to striking at the heart of it

Wotherspoon’s first trip was in 2013, when he gave up a holiday back in his native Australia to fly to Africa.

“I didn’t know what I was going to do when I set off to Tanzania,” he says. “I wasn’t even sure if I would get in because my website criticised the president and the ambassador wasn’t happy, but at the airport I had no trouble.

“Just before I left [Hong Kong], a lady who works for the No 1 newspaper there emailed me asking to use material from my website and I told her I was actually coming to Dar es Salaam. She helped me meet families [of about 30 Hong Kong inmates] and I got blanket coverage in her newspaper for five or six days.

“She introduced me to other media and I did radio and TV interviews covering the whole country. It lit a fire and the Tanzanian authorities cracked down on security at their airports. Some of the big fish were arrested. It caused a real rumpus.”

Supported by donations from Hong Kong supporters, Wotherspoon went to Kenya the following year, and South Africa, Zambia and Indonesia last year. In South Africa, he worked with a television station to produce a prime-time documentary warning of the dangers of trafficking.

“A Hong Kong judge showed the whole programme in court because one case concerned a woman sent by her aunt, who recruited other people as well, and the judge said this would do a great deal to stop people from Africa carrying drugs to Hong Kong,” he says.

Wotherspoon’s campaign has seen a sharp fall in the smuggling of drugs from Africa to Hong Kong, with arrests tumbling from 45 for the continent in 2015 to just three last year. But, he says, vital information from mules that could lead to the arrest of “big fish” is routinely ignored.

That point has not been lost on judges dealing with cases in which Wotherspoon has supported the couriers. In his written judgment on a 2014 case, in which he sentenced a 28-year-old to 14 years for smuggling 1.1kg of cocaine into Hong Kong from Peru via Brazil, High Court Judge Kevin Zervos criticised customs officers for failing to ask for any personal information or background from the defendant, and making no contact with their counterparts in the two South American countries.

“What astounds me most of all is that vital information has been overlooked and not used for further inquiry or intelligence. Far greater effort should be made in the investigation of these cases to identify the ringleaders and organisers […] Dealing with the offenders who bring the drugs into Hong Kong is one solitary aspect of the problem and goes nowhere near to striking at the heart of it.”

“Hopefully the authorities will wake up and realise it is not a department matter but an international matter that needs cooperation not only with the investigating authorities in Hong Kong, but also the investigating authorities [in] other countries.”

Barrister John Wright, who has prosecuted about 10 trafficking cases in the past two years, says many Hong Kong lawyers and judges believe sentencing guidelines for drug mules are in need of review.

“I don’t think it’s justifiable because […] sentencing is almost entirely based upon the quantity of narcotics being carried,” he says. “If you’re carrying a kilo and a half of mixture and it has 900 grams of actual cocaine, you are sentenced on the 900 grams of cocaine. How does the courier know how pure it is? Often they don’t know even the weight because it is all pre-packed.

“The other thing […] is that no account is taken of the role of the couriers, and how high up or low down they are in the hierarchy. In Hong Kong, the courts don’t differentiate except in relatively minor ways. Courts in many other countries do take into account the role of the defendant. There are one or two quite senior judges who also don’t agree with our approach and are not happy with the sentencing guidelines.”

Responding to Wotherspoon’s claims that customs and police act on tip-offs from informants active in the drug trade, Wright points out that the tip-offs may be given through the syndicate in systemically corrupt countries of origin rather than directly to Hong Kong contacts. This means the “big fish” are harder to trace.

This is international trafficking and the horizon has to be broadened. Hopefully the authorities will wake up and realise it is not a department matter but an international matter

“Senior members of syndicates don’t normally get their hands dirty,” he says. “They use other people. They are also very careful how they use phones and pass on information.”

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a senior law enforcement officer involved in investigating drug trafficking cases in Hong Kong says there is no will or incentive for police and customs officials to pursue more senior members of drug syndicates.

“Most people are just interested in justifying themselves, keeping the bosses happy and putting cases on the table,” he says. “If you tackle the problem systematically and fully develop and share intelligence it can be done, but [...] the incentive isn’t there because it’s hard work and takes a lot of time and we don’t have the resources or time. Bosses want cases on the table. If you try to get resources for something more ambitious, there aren’t any.

The Hong Kong Customs and Excise Department declined to give an interview to Post Magazine and would not directly answer questions about the use of informants and the alleged failure to act on information offered by arrested couriers. In a written statement, a spokesman said the department cooperated closely with local, mainland and overseas agencies to exchange intelligence and “smash the source drug supply to Hong Kong or to other places via the city”. A total of 108 cases of drugs being smuggled into Hong Kong were detected through operations with overseas and mainland counterparts in 2017, the statement said.

It added: “The department has a zero tolerance for narcotic-related criminal activities. In-depth, sophisticated and careful investigations will be launched into each case with the highest degree of professionalism and integrity, while prosecution will be conducted wherever evidence sustains.”

Pressed on the criticisms levelled by Wotherspoon, a spokeswoman would say only, “We spare no effort to gather and thoroughly follow up on drug intelligence from various sources, including but not limited to the arrested persons.”

“We take stringent enforcement actions against all forms of illicit drug trafficking and continue to augment the cooperation with local, mainland and overseas law enforcement agencies in combating cross-boundary drug trafficking activities and interdicting the flow of illicit drugs in Hong Kong,” it said. “The force spares no efforts in identifying and arresting those persons engaged in drug trafficking, in particular those drug syndicates which exploit minors, juveniles and foreign nationals.”

Meanwhile, as judges consider what would be a major change in the way drug traffickers are dealt with in Hong Kong, Wotherspoon’s campaign marches on.

He has written to the current and previous chief executives asking for support but has been turned down by both. He failed to run IK to ground in Bangkok but presented written evidence to the High Court on behalf of Li. The jury was unable to reach a verdict and she is now in custody awaiting a retrial.

Wotherspoon has since flown to countries in South America and the Caribbean to spread his message to would-be traffickers, visit families and collect evidence that might help incarcerated drug mules.

Wotherspoon’s fearlessness often places him in tough situations. In Brazil, in January, for instance, he ventured alone into the recesses of a shopping mall frequented by a Nigerian drug smuggling gang.

“I said I wanted a haircut and I wanted to meet some Nigerians. I was taken to a group of 10 to 12 Nigerians who were livid when I explained why I was there,” he recalls in the same matter-of-fact tone another priest might use to describe the feedback from his Sunday morning sermon.

“The man who took me there hurried me out and said, ‘If you don’t want to lose your bag and your passport and your money, get out of here and go back to your own country.’ At that point, I must admit I was a little scared and I did wonder to myself, ‘What am I doing here?’ But I got away.”

In Sao Paulo, as in Bangkok, it seems Wotherspoon’s guardian angels were watching over him every treacherous step of the way.

Details of Father John Wotherspoon’s campaign are available at v2catholic.com.

Study reveals Hong Kong’s appalling record of convicting drug lords

Low-level drug mules are convicted at a rate of more than one a day in Hong Kong’s High Court while only one gang organiser or senior syndicate member is sentenced every eight months, a study provided to Post Magazine shows.

An analysis by former deputy director of public prosecutions John Reading SC found that of 1,619 traffickers convicted from 2012 to 2015, only six were organisers or senior gang members, while 1,519 (or 93 per cent) were couriers, apprehended either in Hong Kong or while trying to enter or leave the city. The remaining 94 cases mostly involved so-called storekeepers caught with drugs in Hong Kong.

Reading’s study also found that sentences for drug-trafficking offences were more severe in Hong Kong than in the 17 other jurisdictions surveyed, with a 22-year starting point for trafficking offences involving 1kg of a class-A drug compared with 20 years in Turkey, 15 to 20 years in Slovakia and 10 to 17 years in New York.

Hong Kong was the only jurisdiction surveyed, apart from Iceland and Austria, not to consider the role and seniority of the offender in the sentencing process. Hong Kong was also one of only six jurisdictions where previous good character was not recognised as a mitigating factor.

The average sentence over the four-year period in Hong Kong was nine years and nine months, while the highest sentences given out were to a 37-year-old sentenced to 32 years for trafficking 33.6kg of cocaine, and a 45-year-old sentenced to 33 years and six months for trafficking 11.9kg of cocaine and 410 grams of crystal methamphetamine.

Because 16-year-olds are tried in adult courts in Hong Kong, prosecutions over that period included 82 minors. All but two received substantial jail terms and cases included a 16-year-old sentenced to 17 years for trafficking 1.9kg of ketamine.

“The heavy sentences imposed for the offence in Hong Kong have not resulted in a significant reduction in drug trafficking cases over those years,” Reading concluded.