Escape from communist Czechoslovakia: how one man crossed the Alps to freedom

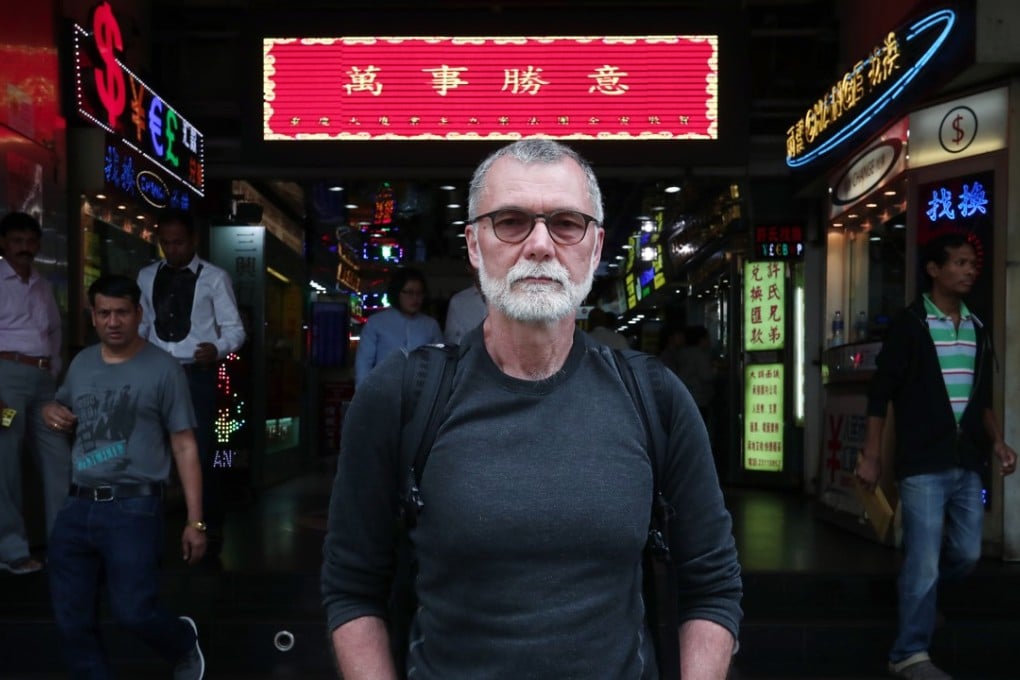

Geologist and mountaineer Jarek Jakubec, who believes life as a refugee in the 1980s was easier than it is for today’s exiles, says leaving his parents behind was the hardest thing

Active resistance I grew up in Czechoslovakia, in the heart of Europe. We spent the weekends at my grandfather’s farm in the country, and during the week I went to school in Brno city, played soccer and was a naughty kid like anybody else. I read lots of travel books and dreamed about the countries, but couldn’t go.

During 1968, when my country was invaded, my father was active in the anti-communist underground. The Russian occupation had a major impact on me as an eight-year-old boy. I remember the resistance meetings in our house. I remember tears and frustration that the nation did not pick up arms and fight. After the Russian occupation, my father was beaten during interrogation by secret police. But he remained silent and they had to let him go.

Following national service in the army, I worked in geological surveys in the mountains, but because my father had a problem with the police, there was no chance I could get a visa to the places I wanted to go. So after university we decided, if we can’t go legally, we’ll go illegally. I was 27 years old and just married (to Dana).

Climbing the Iron Curtain My father always encouraged me to leave the country, and I viewed it not as a cowardly escape but as a form of resistance. I am glad that I found the courage to leave. It was not the fear of escape or being caught or killed crossing the border, it was finding the courage to leave my parents behind and possibly of not seeing them again. It was the hardest decision I have made in my life. I will forever see my father and mother waving at us in tears as the train was pulling away from Brno railway station. It was 1987.