Too many men: China and India battle with the consequences of gender imbalance

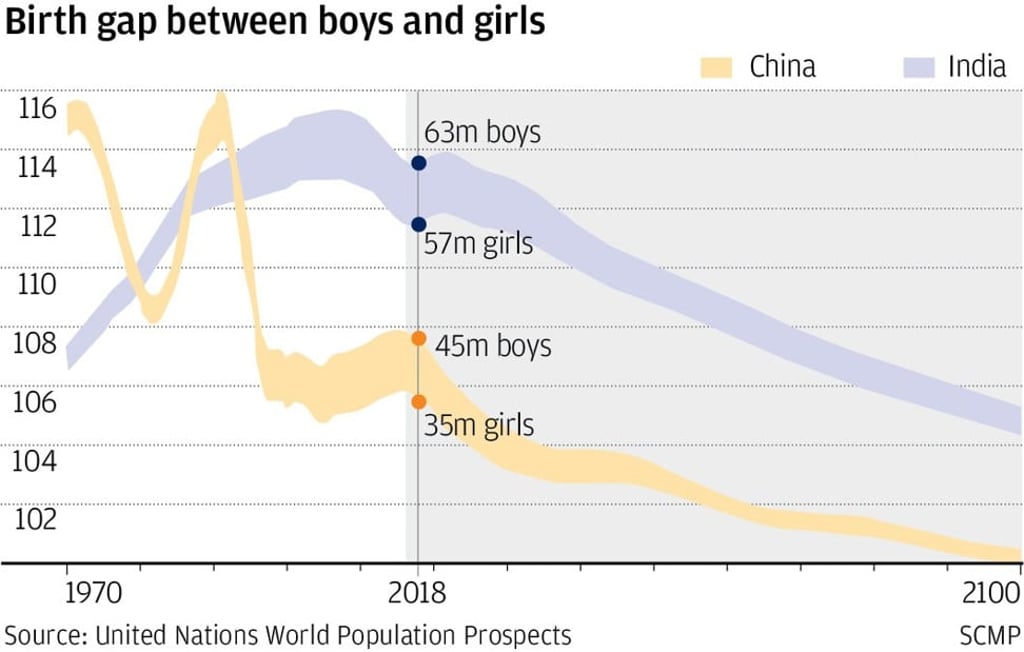

In the world’s most populous nations, men outnumber women by 70 million. Both countries are trying to come to grips with the policies that created this generation of gender imbalance

Nothing like this has happened in human history. A combination of cultural preferences, government decree and modern medical technology in the world’s two largest countries has created a gender imbalance on a continental scale. Men outnumber women by 70 million in China and India.

The consequences of having too many men, now coming of age, are far-reaching: beyond an epidemic of loneliness, the imbalance distorts labour markets, drives up savings rates in China and drives down consumption, artificially inflates certain property values and parallels increases in violent crime, trafficking or prostitution in a growing number of locations.

Those consequences are not confined to China and India, but reach deep into their Asian neighbours and distort the economies of Europe and the Americas. Barely recognised, the ramifications of too many men are only starting to come into sight.

“In the future, there will be millions of men who can’t marry, and that could pose a very big risk to society,” warns Li Shuzhuo, a leading demographer at Xian Jiaotong University, in Xian, Shaanxi province.

Out of China’s population of 1.4 billion, there are nearly 34 million more males than females – more than the entire population of Malaysia – who will never find wives and only rarely have sex. China’s official one-child policy, in effect from 1979 to 2015, was a huge factor in creating this imbalance, as millions of couples were determined that their child should be a son.