December 1941: British officer’s diary describes final days of Battle of Hong Kong

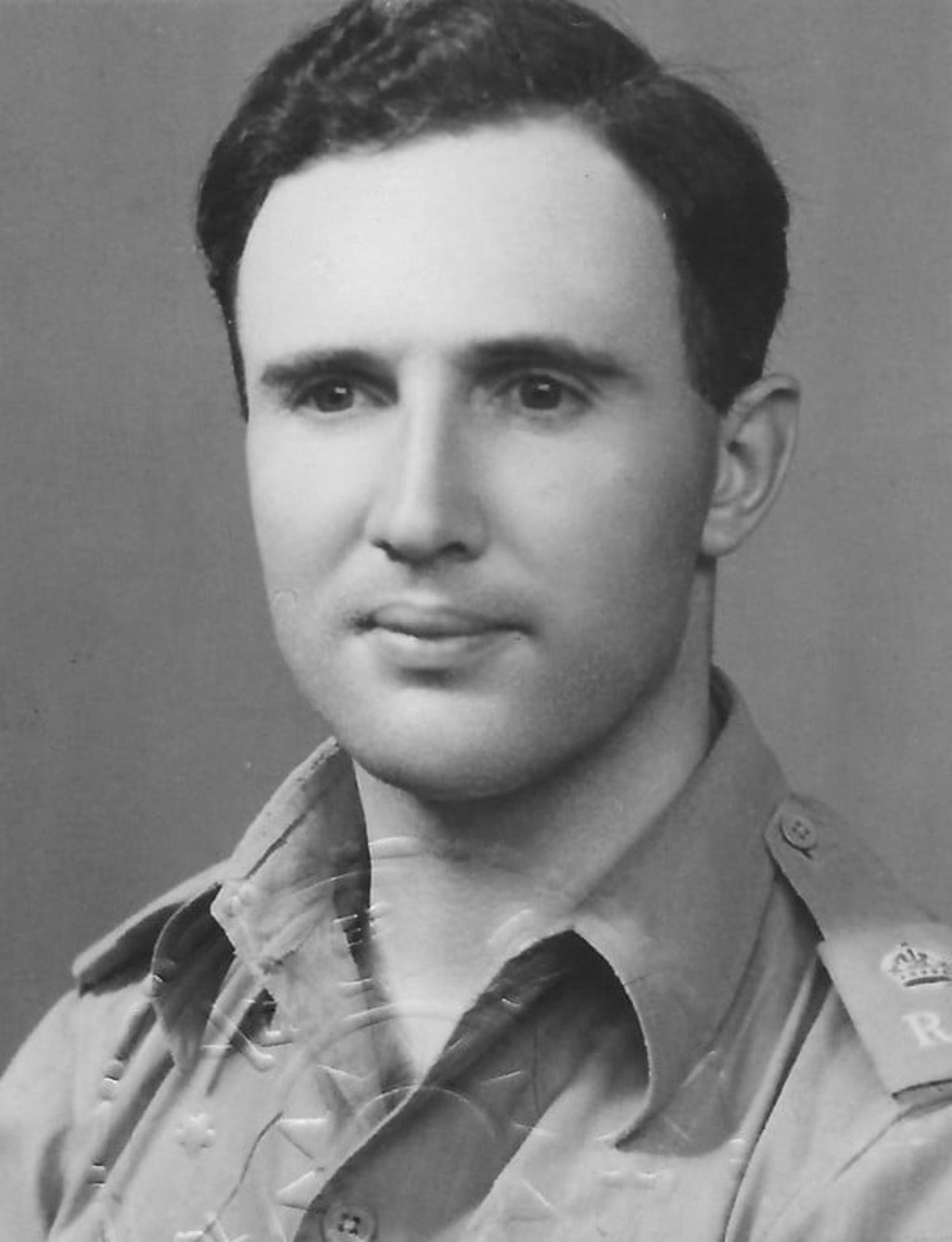

In late 1941, Major John Monro found himself at the centre of battle. The following account of the struggle between the Allied and Japanese forces is taken from Mary Monro’s new biography of her father, Stranger in my Heart

My father joined the British army as a Gentleman Cadet in 1932, at the age of 18. I suspect he may have been drawn to the prospect of an active life of adventure, preferring that to years of studying for an office-based career. He was commissioned as an officer in 1934 and sent to Hong Kong in 1937.

Dad joined 8th Heavy Brigade, Royal Artillery, and assumed command of a Chinese troop on its formation in 1938.

In 1940, Dad was appointed to the Hong Kong Singapore Royal Artillery (HKSRA), but by the time of the Battle of Hong Kong, in December 1941, he was based at HQ China Command, Hong Kong. In late November 1941 my father had been promoted to Brigade 19 Major.

At this time there were rumours and false alarms about the imminence of war with Japan, but it never seemed to come to anything. Dad comments, in diaries written at the time, on the last-minute change of plan for the defence of Hong Kong following the arrival of two Canadian battalions in November 1941:

For the past two years the intention had been merely to deny the use of the harbour to the enemy and to hold the island at all costs. It was realised that it was impossible to hold the colony in sufficient strength to enable it to be used as a naval base. No attempt was to be made to hold the mainland or Kowloon. The arrival of the Canadians entailed great changes in this plan. In addition to the island, Devil’s Peak Peninsula was now to be held at all costs. The “inner line”, a great belt of pill boxes and wire, constructed in the time of General [Arthur] Bartholomew [Commander 1935–38], on the northern slopes of the ring of hills encircling Kowloon, was to be held in force by three battalions for about six weeks, while the island would be held against any attack from the sea by the coast defences.

I am indeed convinced that it was this wretched word “prestige” which over-ruled all other arguments. Useless for me to point out that if war came, we should lose far more prestige by a short and unsuccessful siege, than by voluntarily deciding not to try the impossible. And, as I also pointed out, after the war Hong Kong would belong to whoever won the war.

I had much reason to remember my arguments when I arrived at Chungking 14 days after Hong Kong fell; the majority of Chinese were not prepared to let me forget how much prestige the loss of Hong Kong had cost us.